Note: This article contains spoilers for up until the end of Chapter 3 in Red Dead Redemption II.

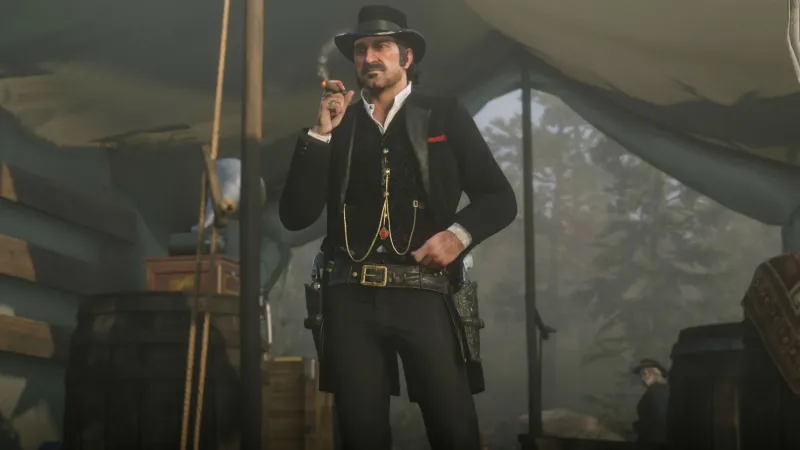

“That is a young boy. That is not the way you do things.” With a few simple words, Dutch Van Der Linde delivers a menacing ultimatum to the wretched Braithwaites, who have kidnapped John Martson’s son to get back at the Van Der Linde gang for interfering in a regional feud. It’s all pretense. For all his eloquent speech, Dutch has made up his mind before the gang has rolled into the gates of Braithwaite plantation. He’s not looking for a solution. Jack’s kidnapping is a problem that needs to be solved, sure, but it’s also an excuse to vent his frustrations in that old familiar way: through bloodshed.

The ensuing battle is only a battle in the sense that both sides have guns. Arthur, Dutch, and the rest of the group rip the Braithwaites to pieces in the span of five minutes and set the plantation house ablaze. The entirety of the “Blood Feuds, Ancient and Modern” mission is a grisly, gripping scene that’s not only fun to play through but also showcases the best of Red Dead Redemption II’s story, which is about entropy, a gradual descent into chaos and disorder. Everything here works. The voice of an operatic singer chillingly married to a crescendo of violence, with bloody bodies falling over balconies and going still in the dirt, Dutch’s explosive rage as he growls at Catherine Braithwaite before putting a bullet in her last living son, and the final shot of Catherine running into the burning vestiges of her legacy as the gang walks away in the night, their questions answered and their lust of violence quenched. Out of all the classic moments to emerge from Red Dead Redemption II, “Blood Feuds, Ancient and Modern” might be the best one, and it wouldn’t work without everything that came before it.

Red Dead Redemption II is a game that’s value is rooted in payoff. A lot of video games, the vast majority of them I’d wager, are about the immediacy of rewarding progression systems. It’s something that gamers have had trained into them from the early arcade days, from watching your high score eclipse your rival in Pac Man to unlocking characters in Smash Brothers and acquiring new skills in RPGs like The Witcher III or even acquiring new cosmetic options and loadouts in shooters with RPG-lite progression systems like Call of Duty or Titanfall. Similarly, stories have had to adapt to keep up alongside the rhythm of games. Rarely in even some of the most renowned narrative-driven experiences do you have long lulls in action. Both Mass Effect and The Last Of Us, considered watershed moments in how to tell a story in games, throw enemy encounters your way and reward you with upgrades at a steady pace to keep you engaged on multiple levels.

Red Dead Redemption II isn’t interested in constantly courting your engagement and that’s one of the game’s greatest assets. The entirety of Chapter 3, which finds Dutch’s gang trying to play both sides of a violent feud between two Southern rich families (the Grays and the Braithwaites in the small town of Rhodes), is the best example of this. A lengthy campaign of missions has players doing various tasks that further the feud, like stealing horses from the Grays to selling Braithewaite moonshine in a Gray bar. It goes on for a while, with several mundane tasks that probably don’t match up to the excitement of gunning down legions of bandits or lawmen. However, they do an important thematic job in cementing just how in over their head the entire gang is.

From the outset of Red Dead Redemption II, Dutch and Hosea see themselves as charismatic leaders and grifters. Maybe at one point they were, years ago, before technology and society started bearing down on the wild west, with rich tycoons pouring funding into private law armies like the Pinkertons to wipe out outlaws. More than anything, the Van Der Linde gang is living on borrowed time and refuses to see the writing on the wall. Early on Arthur, like us, gets a sense that the noose is tightening during this excursion into Rhodes and that the families probably aren’t as dumb as Dutch thinks they are. “You don’t think they remember us from when we burned their fields?” he hisses at his fellow members during one mission, only for his point to be brushed aside. In its desperation for survival, the gang has gotten clumsy, its leaders descending into ruin and insanity. For a large part of the Chapter 3, you feel that unease and desperation, with Dutch and Hosea throwing caution to the wind – until the danger becomes boring.

Part of why the shocking moment of Sean’s death, which is when the finale of the chapter kicks off in earnest, works as well as it does is because of the seductive safety that emerges during the onslaught of the mundane. The succession of missions going off without a hitch lures you into feeling safe in the moment because, well, if neither family has done anything yet, maybe the gang really is safe. Maybe they have gotten away with the ultimate con. That arrogance comes with a steep price, the slow burn chapter erupting in an explosion of hate and anxiety as the gang continues to ride full on toward its destruction, no salvation in sight.

So much of Chapter 3 is pure buildup to two missions that lasts less than 10 minutes together but every single one of these minutes is amazing and more than worth the ticket price of some patience. I’ve replayed the mansion fight five times since completing the game and continue to find new details that I love but mostly I’m in awe of how pitch perfect the sequence is in capturing who the gang (which the game has gone out of its way hitherto to present as at least partially noble) is deep down: desperate people capable of becoming monsters when pushed into a corner. The juxtaposition of Dutch’s noble sentiments about recovering Jack Marston with the awful display of him dragging the vile but defenseless Catherine down the stairs by her hair and forcing her to watch as they butcher her children is chilling in how it presents the duality of people pushed to the edge.

Red Dead Redemption II is a divisive game and one that is not for everyone. I adore it to pieces but acknowledge that many of its quirks and flaws are valid annoyances. However, I do not think its pacing is a flaw. Instead, I think that the expectation of games to offer experiences that constantly reward you by making you feel powerful or by never testing your patience is the issue here and I’m relieved to see something as big as Red Dead Redemption II push back against that setup. In the years to come, I hope Red Dead's success spurs publishers and developers to take a new approach to progression, sacrificing the immediacy of pleasing the player for narrative or systemic beats that have massive payoff.

For more on Red Dead Redemption II, be sure to check out our Virtual Life on why Arthur Morgan is a better protagonist than John Marston as well as 101 things you an do in the game.

Explore your favorite games in premium print format, delivered to your door.