Be the first to get Game Informer’s August Issue! Subscribe Now

Before work even started on Detroit: Become Human, we were introduced to an android named Kara. As the subject of a 2012 tech demo by Quantic Dream, Kara’s emotional reaction to her newly conscious mind was a microcosm of the themes that would define the studio’s recent work. In Detroit, the Kara we saw six years ago is now a housekeeping android whose character is defined by her relationship with a young girl.

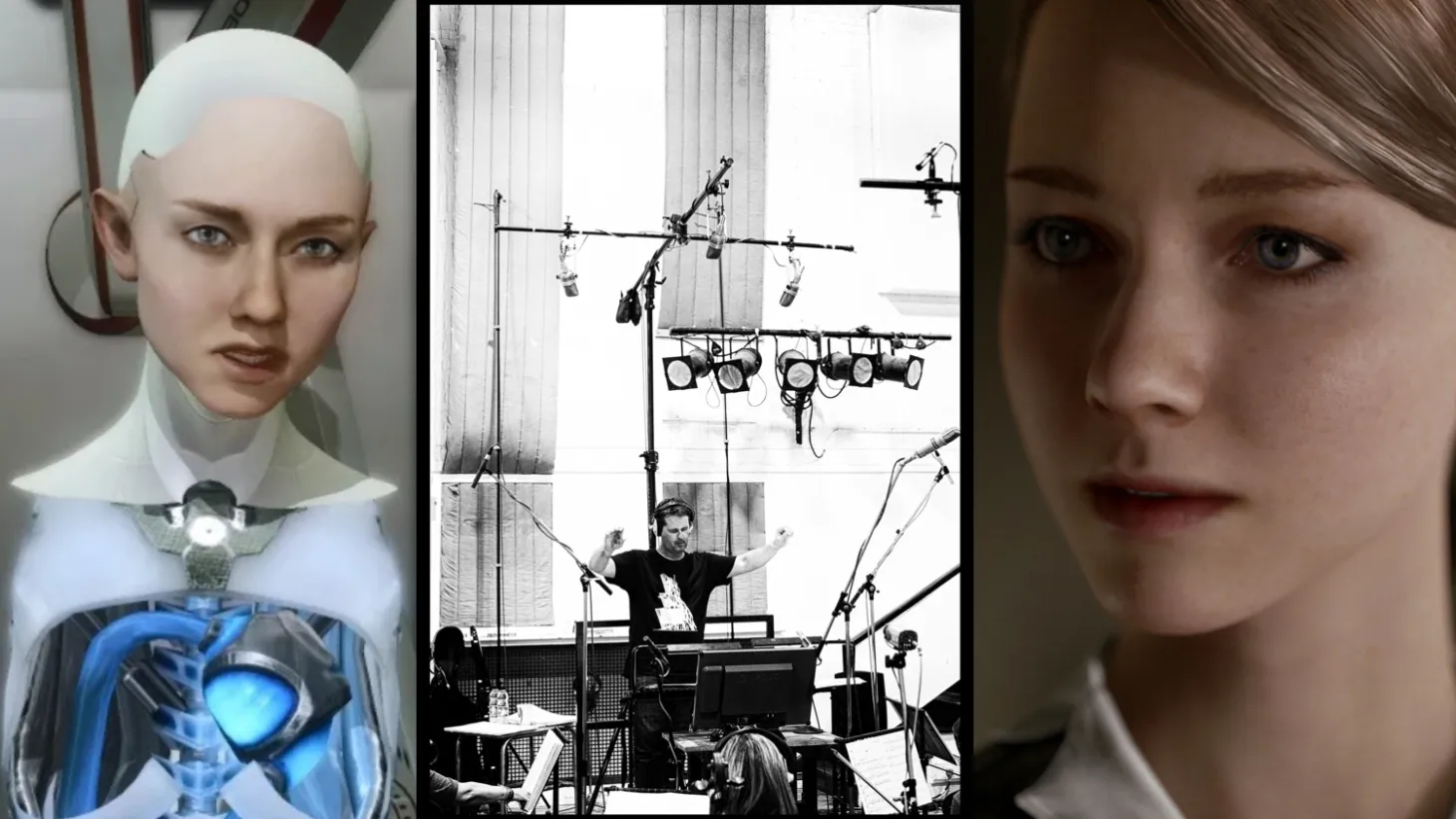

To clearly define each of Detroit: Become Human’s three protagonists, Quantic Dream brought on three different composers to bring life to their individual stories. Kara’s soundtrack was scored by Philip Sheppard, a composer and accomplished cellist. In our interview with Sheppard, he touches on his work with David Bowie, the unique challenges of scoring a video game, and how he sees A.I. shaping the future of music.

Your composing portfolio is extensive, but features relatively few video games. How did you get in touch with Quantic Dream to start work on Detroit: Become Human?

I'm a great believer in regularly writing down my goals and ambitions. I fill notebooks with handwritten lists, things I want to do but that seem out of reach any the time. Writing things down in the past has resulted in some crazy results, including having my music played in space, working on Star Wars and getting to be a producer at the Olympic Games - so it works. Mainly because you put yourself in a frame of mind where you’re prepared for things to happen, by which I mean technically ready. Luck is preparation meeting an opportunity, and, so long as you’re over-prepared you can probably attract, or spot, an opportunity. So, my wish list 18 months ago was headed up with write a soundtrack for a video game. I have it written down in a notebook here.

As far as games go, I was thinking of something small, maybe composing for an app – and then David Cage rang me. Detroit: Become Human turned out to be a little larger than an app.

Detroit’s three protagonists each have their own composer, which implies a deep knowledge of that character. What kind of emotions or motivations were you trying to tap into for Kara?

When I started composing music for Kara, I initially thought that it was going to be about finding a voice from a machine, a kind of mechanical, clockwork fantasy. Therefore, my initial sketches featured a hacked Texas Instruments Speak & Spell (I’m showing my age) and all sorts of clanking whirring instruments. Very soon I realized that the key to her sound was all about the progression from having no soul, to becoming a mother. That’s a vast leap. And it meant aiming for a way more organic approach. Being the father of three very strong daughters, it wasn't difficult to tap into parental emotions.

So, musically I wanted to create a sense of strength and yearning whilst trying to find something simple enough that could work quietly – as well as transpose into large, violent, stressful moments for the fights and chase scenes too. The key was simplicity and feel. Writing simple music is really very hard. It taps into that dichotomy of beauty requiring less, but knowing what to leave out is a skill.

In the end, I whittled it down to a two-note theme over a flickering kind of riff. All 55 pieces about Kara feature these elements – some obviously, some more concealed – but they’re always there. The different thing about writing this soundtrack was that I normally (in a movie) have to write portraits of every character, as well as environments and progressive situations. In the case of Detroit: Become Human, I was wholly focussed on one character. That’s so very unusual. It made me very defensive of her, and a little bit protective. Hell, I was in love with her by the end. I hope the players will be too.

Detroit: Become Human grapples with the legacy and potential future of A.I. In reference to this, you reportedly managed to work in a tribute to the “godfather of A.I.,” Marvin Minsky.

Marvin Minsky was a dear friend of mine, and after he passed away, his family shared his archives with me. As well as being the godfather of A.I. and an expert in robotics, Marvin was also a fantastic composer and pianist. I think there was nothing that man couldn’t do. He had composed many short piano pieces directly onto reel-to-reel tape, hand splicing them with a razor blade and tape, recording them at different speeds to create pitch effects. It was a real treasure trove. One of the pieces sounded so beautiful, I decided to write a symphony orchestra to frame it – a sort of concerto accompaniment.

We recorded 60 musicians in Abbey Road playing along to Marvin’s tape, using The Beatles’ microphones. David Cage hadn’t realized my connections to Marvin, and had actually named a character after him in the game.

My track is called ‘The Minsky Tapes’ and is now hidden in the game. Marvin would have loved Detroit: Become Human and his widow Gloria is fully intending to play it as soon as possible. I believe that our role as artists/musicians/composers is to pass on ideas, and Marvin’s ideas have centuries of wisdom yet to run. How great will it be if a teenager playing the game seeks out Mr. Minsky as a result of a buried item in this game?

You once collaborated with David Bowie. Perhaps not coincidentally, Bowie’s only direct game appearance was in Omikron: The Nomad Soul, which was an early Quantic Dream game. Did David Cage know about this connection?

David Cage actually knew of me because of my work with David Bowie. I worked extensively on a track called “everyone says hi” on his album Heathen.

Somehow, I had persuaded Bowie to replace most of his band with 44 cellos on this particular track, every single one of them played by me!

I’ve always been heavily into multi-tracking, whether recording one line at a time or live looping my cello.

I ended up using the same technique from the Bowie recording over the orchestra in the big Kara theme where they escape (hopefully) from Todd. In that sequence, there are actually 77 separate layers of my cello in the section where the track gets really big. To be honest, I think David Cage was happy that he got more cellos than David Bowie!

One of Detroit: Become Human’s biggest features is its reactivity to each player’s choices; different paths may result in dramatically different consequences. How did you approach this when scoring each scene?

Once I decided on a theme for Kara, it was a question of writing many variations in wildly different moods. These ranged from a music box to a fairground carousel, from violent chase scenes to reflective piano pieces. Having said that, the clever bit was really the implementation by the music team at Quantic Dream, Mary Lockwood and Aurelian Baguerre, who were able to break the music down into its component parts, rework it, and layer it into dramatically clever mood pieces. They did an amazing job and it's one of the first times I've handed over the various toolkits of my music knowing that what will come back will sound better than what I had envisaged.

Detroit seeks to challenge our notions of the difference between A.I. and humans, especially when it comes to topics like how we work. David Cage has referenced the idea that in 20 years, we may all be replaced by androids. Given your line of work, have you thought about the influence A.I. and technology may have on the world of music?

The history of music is almost entirely driven by technology, so these are not threats to musicians, but actually opportunities to enhance our work, even broadcast in a different way and open up new pathways that hopefully lead to goosebumps. In the early 1600s, Claudio Monteverdi was already experimenting with surround sound, in the 18th Century, Beethoven was testing a piano tuned in quarter tones, and once Thomas Edison had popularized recording mechanisms it opened the whole concept of broadcast and replication – a foundation stone of modern computing (with some help from Ada Lovelace and Mr. Babbage of course). Technology has always driven music, and vice versa.

The music world had already panicked in the 1980’s when it seemed musicians would be replaced by synthesisers, but in fact what happened was that the performers and composers became enhanced by them. Indeed, a Clavinet sounds pretty boring until Stevie Wonder sits down at it… And so far, no A.I. is going to replace Stevie … yet.

Nowadays the Billboard top 100 is full of musicians who can actually sing and play. I’m not sure that was true 30 years ago when we all thought tech was the future death knell of music. In short, I believe that technology/A.I. is a set of incredible tools. And A.I. means nothing without meaningful human interface, and I think that’s kind of the point of this game, too.