007 First Light headlines our newest issue about the most anticipated games of 2026 and beyond. Subscribe now!

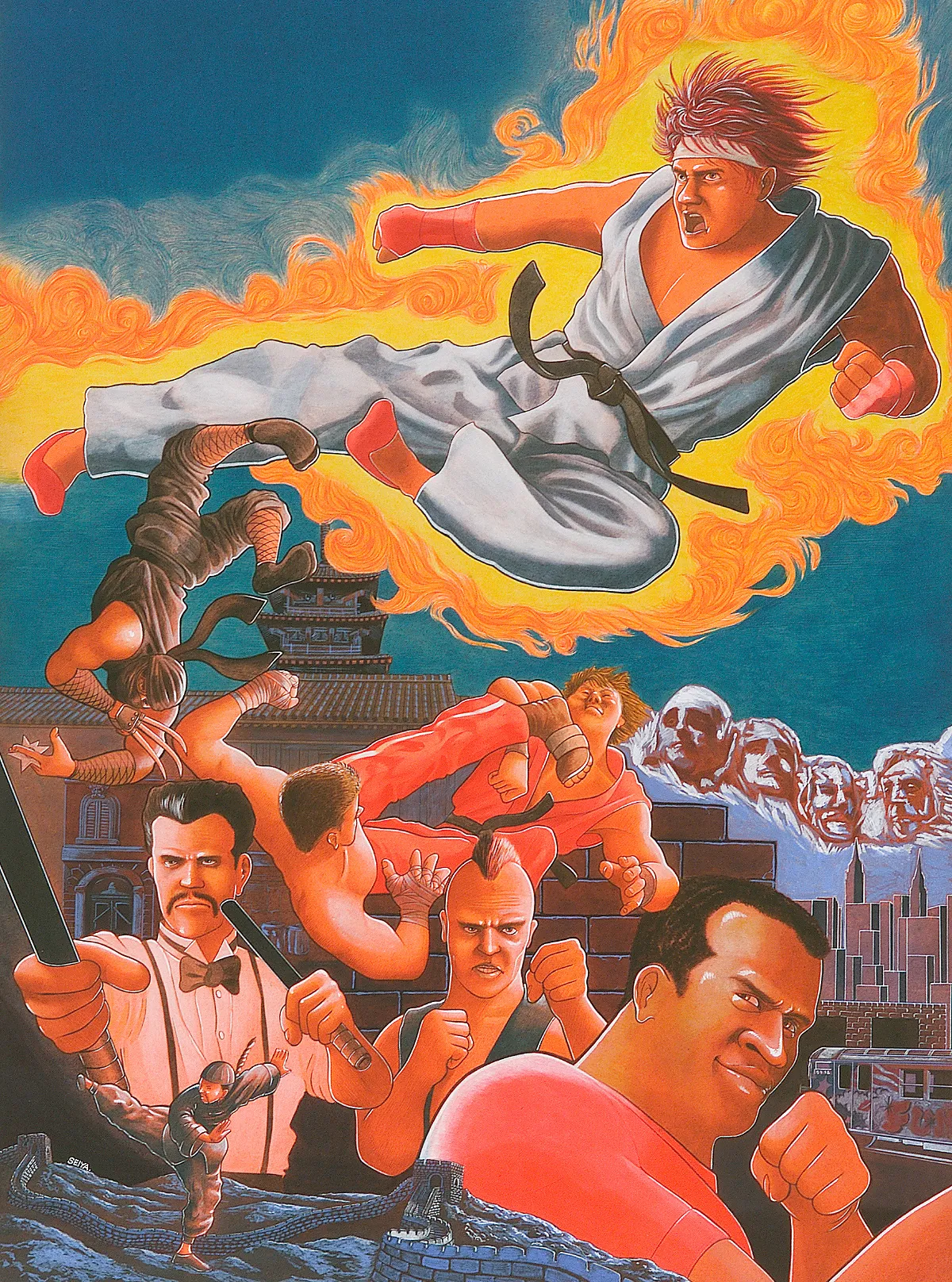

If you walked into an arcade in the 1990s, it undoubtedly had a Street Fighter II cabinet. If you went at the right time, you probably even saw a crowd gathered around it. As one of the most profitable games in arcade history, Street Fighter II drew more than its fair share of quarters and tokens during the arcade heyday. But the franchise transcends that one moment in time. To say that Street Fighter has sparked multiple revolutions in its genre throughout its history is not far-fetched.

Arcades aren’t omnipresent the way they once were, but the Street Fighter name has endured the ever-shifting grounds of the games industry. The fierce fistfights made the leap from mall game rooms to the living room, the internet, and even tournaments broadcast to massive, international audiences. As the franchise turns 35 years old, we met with the people involved to understand the series’ origins and how it remains relevant three-and-a-half decades later.

You’d be forgiven if you’ve never played the original Street Fighter. Even by late ’80s standards, it wasn’t particularly remarkable outside of its concept. But that initial game laid the all-important groundwork for the franchise and genre. Bored in a long meeting with Capcom’s sales team, designer Takashi Nishiyama caught himself daydreaming. As the meeting stretched to the near two-hour mark, he was struck by inspiration.

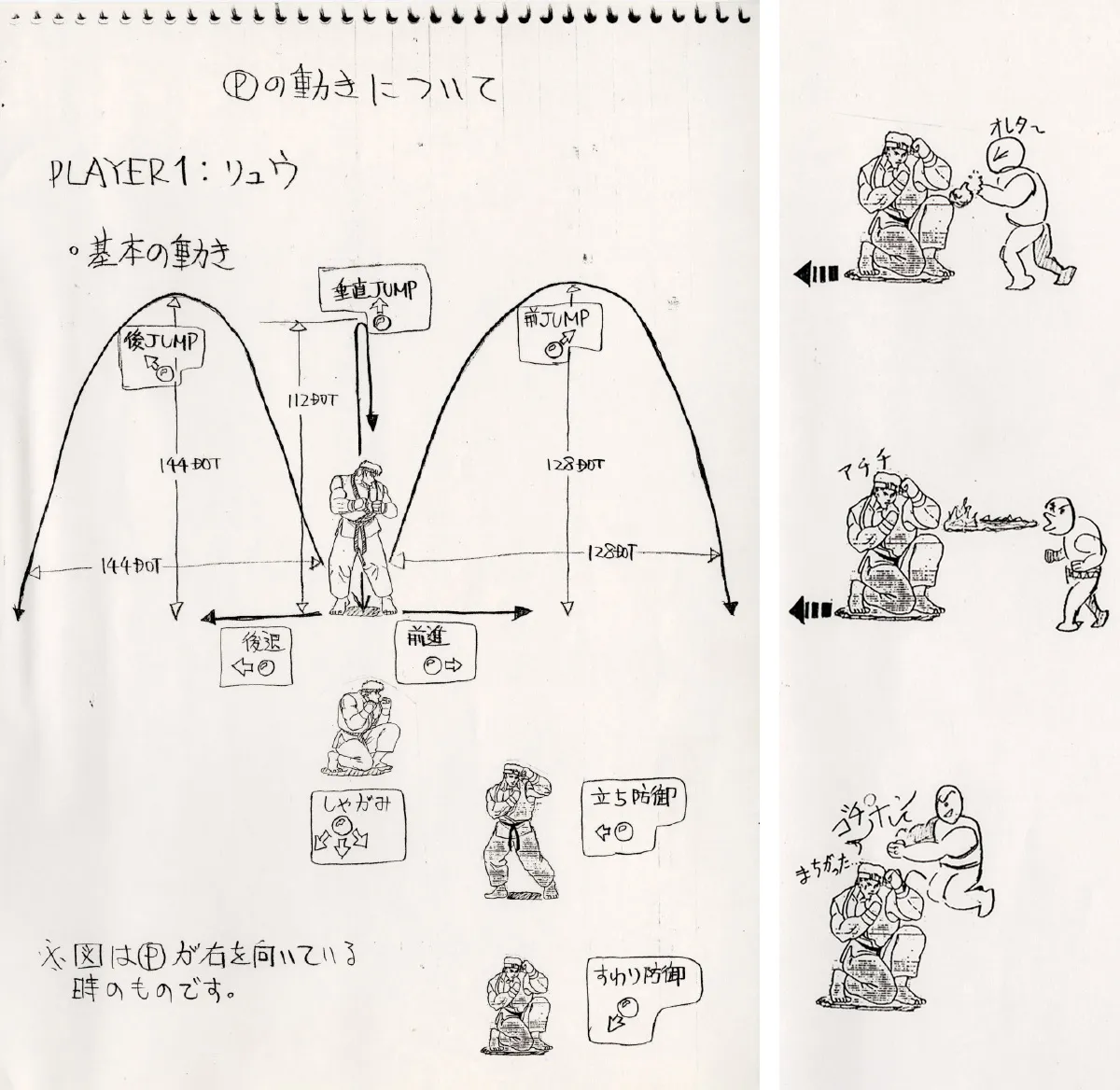

As he recalled to Polygon in 2020, Nishiyama began sketching his idea on a piece of paper. Inspired by the one-on-one boss battles in the 1984 beat ‘em up game Kung-Fu Master (which he also worked on), as well as Bruce Lee’s 1972 film, Game of Death, Nishiyama jotted down the basic concept of two characters facing off in one-on-one combat. Once he had it on paper, he showed it to producer Yoshiki Okamoto, sitting next to him in the meeting. Okamoto thought the idea looked interesting, so Nishiyama created a design document out of the concept and presented it to higher-ups, including planner Hiroshi Matsumoto. Once Capcom green-lit the project, Nishiyama and Matsumoto worked together to flesh out the idea.

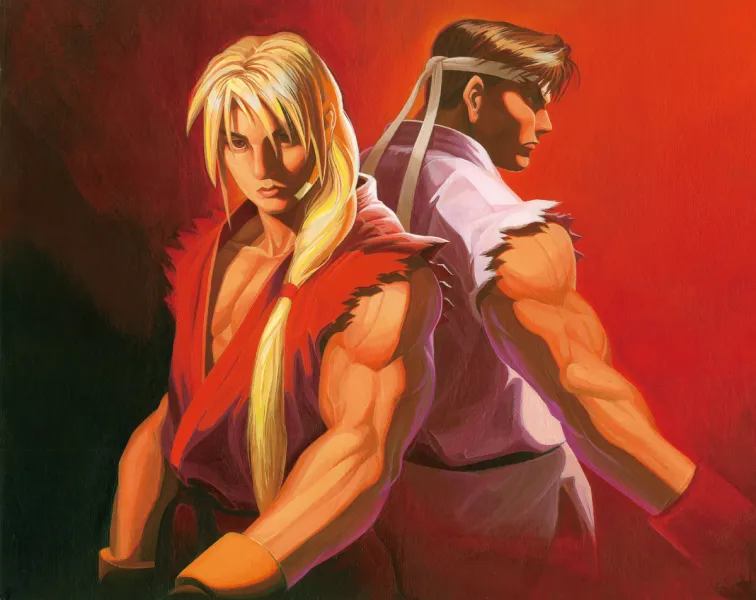

Pulling from their interests in martial arts, Matsumoto and Nishiyama immediately started brainstorming about the kinds of fighters and moves they should put in the game. While the game universe today includes several colorful characters with distinct fighting styles, initially players could only control Ryu, representing Japan, and Ken, representing the United States. Ryu and Ken handled identically to one another, possessing the same attributes, moves, and techniques. This allowed for completely balanced one-on-one competitive combat against another player, but more importantly, it let the team remain on budget and schedule.

When Street Fighter arrived in arcades across the globe in 1987, Capcom shipped two distinct cabinets. The first cabinet carries the now-standard six-button configuration, with each button representing a different power level for a kick or punch. The second, known as the “Deluxe” cabinet, replaced the six buttons with two pressure-sensitive pads: one for punches and another for kicks. On that arcade machine, Ryu or Ken threw their attacks based on how hard players hit these pads. As you might imagine, these Deluxe cabinets weren’t long for this world; they essentially encouraged players to damage the machine and were replaced mainly by the more popular six-button alternative.

While the first Street Fighter is worth revisiting today solely as a historical curiosity, that nascent gameplay style, as stiff and barebone as it was, aptly laid the groundwork for what came next. With a sequel given the go-ahead by Capcom, the developers of Street Fighter began working on the game that would change the world forever.

Following the commercial success of 1989’s Final Fight in the United States, Capcom decided to focus development efforts on games in the fighting genre. Part of that involved developing a sequel to Street Fighter. Both Nishiyama and Matsumoto left Capcom shortly after the launch of the first game, so Capcom tapped the man Nishiyama showed the initial concept in that meeting, Yoshiki Okamoto, to produce Street Fighter II. Capcom also pulled in Final Fight designers Akira Nishitani and Akira Yasuda to work as designers on the fighting follow-up.

With the core development team from another series picking up the ball and running with the Street Fighter franchise, the team pulled from a wider array of inspirations. “From my perspective, we were making a sequel to Street Fighter I, but a lot of animations and character designs came from Final Fight, and we tried to apply a lot of the content from that for Street Fighter II,” Capcom creative director and Street Fighter II character designer Shoei Okano says. “But in comparison to Final Fight, Street Fighter II has a lot more animation patterns and more characters.”

The primary goal for Capcom was to create gameplay that matched the promising premise of the original Street Fighter. Taking the popular six-button configuration of the first game, Capcom implemented easier-to-execute commands for special moves, smoother animations and gameplay, and an all-new combo system.

In a 2002 interview with Edge, producer Noritaka Funamizu says he accidentally discovered the combo system as a glitch while playtesting. He noticed that he could string together multiple attacks in a cohesive manner if the strikes were timed right. As Funamizu notes in the interview, this system became a massive part of the franchise.

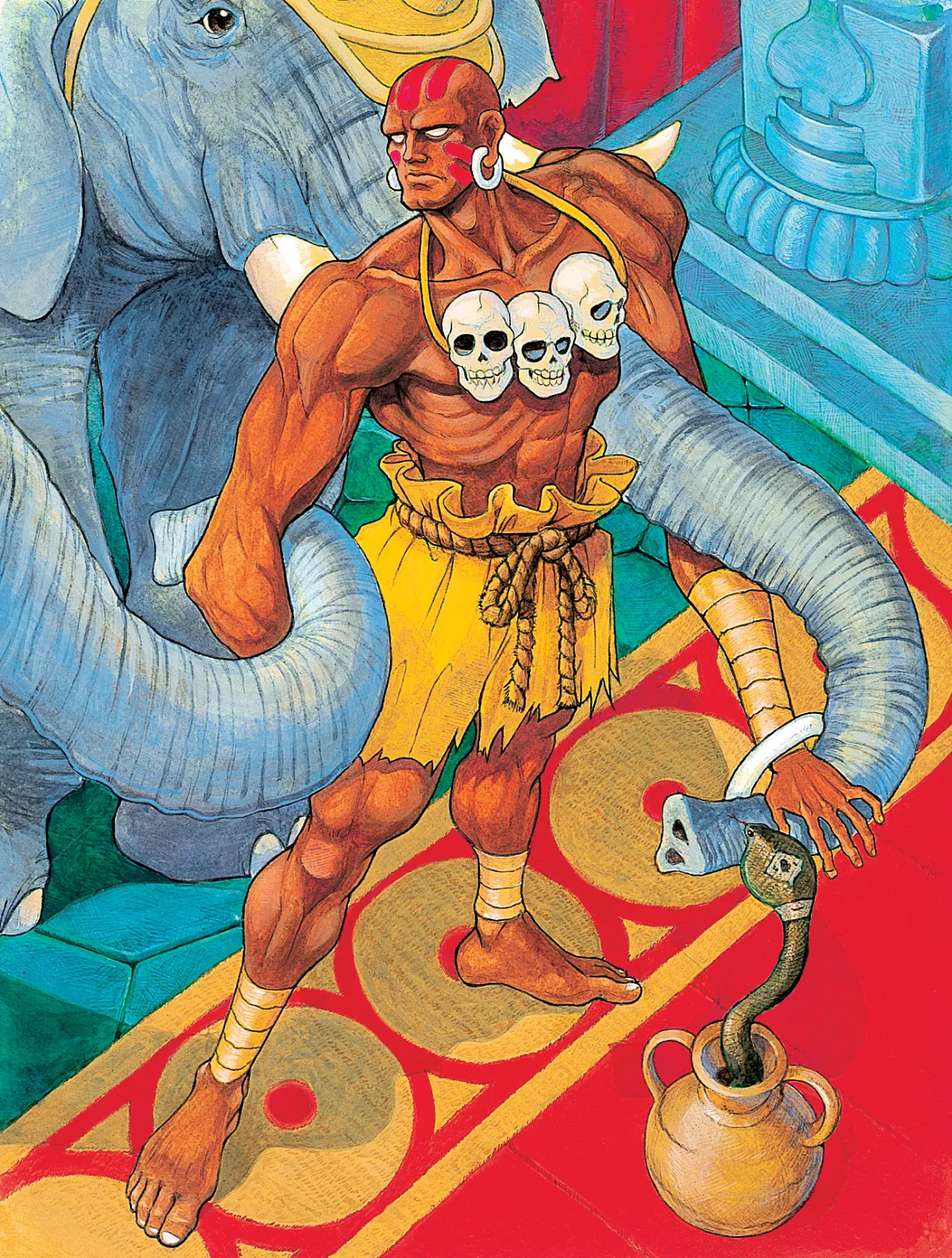

Discovering another major innovation required much less skill and investigation. In fact, it might be the first thing you notice about Street Fighter II: the roster of playable characters. Ryu and Ken remained on the roster, but aside from the boss character Sagat carrying forward, the game featured an all-new cast of unique fighters. Chun-Li, Guile, Blanka, Dhalsim, Zangief, and E. Honda joined Ryu and Ken as playable fighters, while the final challenge of Arcade mode featured a gauntlet against nonplayable characters Balrog (known as “Boxer” in international tournaments), Vega (known as “Claw”), Sagat, and M. Bison (known as “Dictator”).

Once word of Street Fighter II got out to other Capcom teams, the game became a hot topic publisher-wide, hinting to the Street Fighter II team that it was onto something. “Even the developers from other, non-Street Fighter titles would come to play for fun,” Okano says. “We saw that excitement, and we knew we had something going for us.”

Street Fighter II: The World Warrior arrived in arcades in early 1991, less than two years after it entered development. While the game featured countless improvements over its predecessor, it didn’t find immediate success. Capcom attributes this to players not understanding the multiplayer merits of the cabinet and instead focusing too much on the single-player Arcade mode.

“I didn’t really know what to expect,” Okano says. “A lot of stuff came as a surprise, but eventually we were able to run a location test at one of the local arcades where we brought in a test arcade cabinet of Street Fighter II. When we placed it in the arcade, there were a lot of people who rushed in to see the sequel to Street Fighter I. Everyone was super excited to try it out, but even though two players were able to play, most people were expecting only to be able to do one-player battles.”

Capcom quickly shifted its marketing efforts to emphasize its two-player battle mode. The game exploded. After a tepid start, Street Fighter II: The World Warrior became the highest-grossing arcade game of 1991 in the U.S. and Japan and topped the Japanese charts again in 1992. By the end of 1992, Street Fighter II had become the best-selling arcade game of the last 10 years. A new kind of arcade culture formed around Street Fighter II cabinets, as crowds gathered, players put quarters in the little grooves below the screen to claim “next,” and competitive gaming took off in ways never seen before.

The runaway success inspired various other publishers and developers to jump on board with this new genre. “Street Fighter II really invigorated things, and that was a big inspiration for us,” Mortal Kombat co-creator Ed Boon says. “To me, the fighting game genre wasn't even a genre, really. It's not like there was a bunch of games in that category! It was really scattered; every once in a while, one would exist. Street Fighter blew that door open. Mortal Kombat broke the next door open. Between those two games, it suddenly became [a genre] because everybody wanted to get a piece of that. It became a genre based on Mortal Kombat and, before that, Street Fighter's success.”

Though Street Fighter II: The World Warrior was popular, Capcom wanted to create a better experience for players and, in the process, capitalize on the millions of dollars pouring into the cabinets across the globe. To do this, the company started releasing newer versions of the game through all-new cabinets. That first version, The World Warrior, was followed just over a year later in early 1992 by Champion Edition. This new version balanced the original eight playable characters, made the four Shadaloo boss characters playable, and enabled mirror matches for the first time, letting two players fight against each other using the same character.

Capcom didn’t stop there, though. That same calendar year, late 1992, Street Fighter II Turbo arrived in arcades. Turbo added a faster game mode, additional balancing, and new special moves. In 1993, Super Street Fighter II: The New Challengers again balanced the roster while adding four new playable characters. Finally, in 1994, arcades received Super Street Fighter II Turbo, complete with air combos, super combos, and another new character, Akuma. While each of these cabinets represented different versions of Street Fighter II, they all shared in the original’s success; each version reached the number one spot on the arcade charts in both the U.S. and Japan.

However, the game didn’t stay exclusively in arcades, as Street Fighter II experienced similar success on home consoles. Super Nintendo and Sega Genesis received most of the versions alongside the arcade cabinet releases, but Capcom continues to re-release these titles on consoles to this day. Some consoles have even received new versions of Street Fighter II long after its main lifespan. In 2008, PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 received Super Street Fighter II Turbo HD Remix, an HD port with modernized visuals featuring a new art style from the UDON Entertainment team in charge of the Street Fighter comic books, as well as a new soundtrack, further balancing, and online play. Then, in 2017, Capcom released Ultra Street Fighter II: The Final Challengers. This Nintendo Switch-exclusive release added a new first-person mode called “Way of the Hado” and two new playable characters: Evil Ryu and Violent Ken.

Street Fighter II remains one of the most beloved video games of all time, and the accolades, record profits, and community support made it one of the most successful games ever released. Though it was a tough and unprecedented act to follow, Capcom subverted expectations in the succeeding years.

Rather than immediately jump into a numbered sequel of Street Fighter II, Capcom took a detour through the early years of the story. Set after the events of Street Fighter but before Street Fighter II, the Alpha series features younger versions of many fan-favorites. This placement in the timeline allowed Capcom to use characters from the rosters of Street Fighter, Street Fighter II, and even the Final Fight series.

The Alpha trilogy, launching in 1995, 1996, and 1998, introduced now-beloved characters like Sakura, R. Mika, Rose, Dan, and Charlie, as well as mechanics like the gauge-based Super Combo system. Street Fighter Alpha 3 proved to be the fitting send-off for the subseries, improving the Super Combo system through a selectable “ism” mechanic that gave players a choice on how to engage with their gauges. Alpha 3 also included an enormous roster that ranged from 28 to 38 characters, depending on which version you played, and a World Tour mode enabling character customization and more fleshed-out storylines.

On the heels of the Jean-Claude Van Damme and Raul Julia-led Street Fighter theatrical film, Capcom released the Street Fighter: The Movie video game. While still a 2D fighting game, the character models used digitized images of many of the actors, including Van Damme. Despite the star power and trendy graphical style, critics and fans largely panned the game.

Around that same time, Capcom worked with Arika, a development studio founded by Street Fighter II designer Akira Nishitani, to create a trilogy of Street Fighter EX games. These titles ditched the sprite-based characters of previous games in favor of polygonal graphics. Though it features 3D visuals, the EX games still play like the 2D games. It’s an officially licensed Street Fighter trilogy, but the spin-off series focuses heavily on characters exclusive to the EX games, with only five Street Fighter II characters crossing over.

Though the visuals were revolutionary then, the gameplay and lack of a recognizable cast made for a largely forgotten spin-off series that Capcom hasn’t revisited since EX3 launched in 2000. However, the EX titles did give the series at least one gift: canceling. By canceling out of one move and into another, players could string together massive combos.

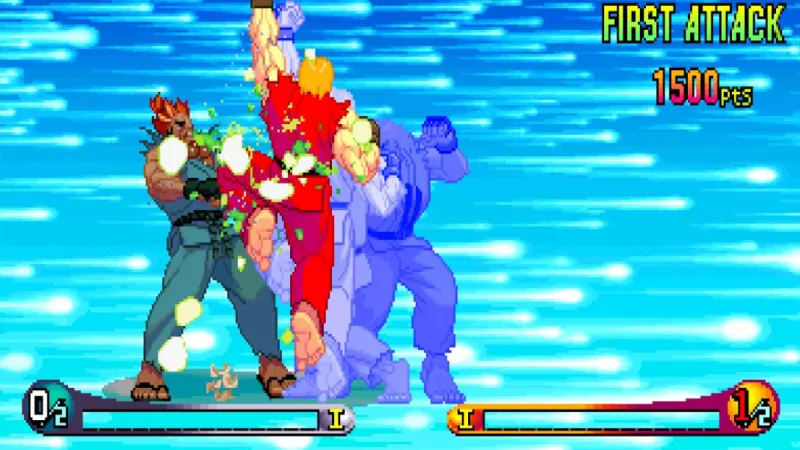

During that period, Street Fighter characters began appearing in crossover titles. Following Capcom’s releases of X-Men: Children of Atom and Marvel Super Heroes, Capcom brought the most popular Street Fighter characters and the era’s most popular Marvel characters together for X-Men vs. Street Fighter. This entry, which first hit arcades in 1996, adopted the 2D fighting style of Street Fighter, but amped up the action and enabled a tag-team style featuring teams of two characters. Less than a year later, the roster was expanded in a 1997 sequel, Marvel Super Heroes vs. Street Fighter, then expanded again in 1998 in Marvel vs. Capcom: Clash of Super Heroes.

The Marvel vs. Capcom franchise spawned four mainline entries and remains one of Capcom’s most popular fighting game franchises, with the Street Fighter characters featuring prominently on the rosters. However, Street Fighter characters have continued crossing over with other prominent franchises and companies, including Tekken, Tatsunoko, SNK, Super Smash Bros., and Power Rangers. Though the success of these crossovers has been a boon for both Capcom and Street Fighter fans, nothing quite matches the excitement surrounding a new, mainline Street Fighter title.

While all these spinoffs and pseudo-sequels were being developed and released to critical and commercial acclaim, the community was still hungry for a true sequel to Street Fighter II. In 1995, in the middle of releasing the Alpha and EX trilogies, Capcom began the development of a new mainline entry in the series. In 1997, it launched Street Fighter III: New Generation.

The title was apt, as Capcom moved away from the iconic roster of characters of Street Fighter II and Alpha, only carrying forward Ryu and Ken. That same year, Capcom released Street Fighter III: 2nd Impact, which expanded the roster with new characters and reintroduced fan-favorite Akuma. Finally, Street Fighter III: 3rd Strike launched in 1999, bringing more new characters, Chun-Li, and a grading system to tell the winning player how well they street fought.

Street Fighter III is also noteworthy for introducing parrying, rewarding players for taking the risk of pressing forward into an incoming attack instead of the standard retreating block many were accustomed to. The parry system complemented the new Alpha-inspired gauge-based Super Arts and the EX-inspired canceling to create what is perhaps the most perfectly paced and precision-based fighting system ever seen.

“While highly flawed in the first game, New Generations, [the parry system] was perfected by Third Strike, the third iteration of SFIII,” esports commentator James Chen says. “And honestly, its story of going from basically a flop in the U.S. to becoming one of the most beloved fighting games of all time here in the States is a long, long journey. […] The parry mechanic remains as one of the most beloved and player-satisfying mechanics ever created.”

Though Street Fighter III didn’t revolutionize fighting games like its numbered predecessor, it perfected the formula. But it was a gem fans didn’t fully appreciate in its time. However, even as competing fighting game franchises flourished under the new trend of 3D visuals and fight planes, the Street Fighter franchise entered the largest lull of its history, and fans didn’t receive a new Street Fighter game for eight years.

Street Fighter relinquished its claim to the throne in the early years of the new millennium. With more players looking to enjoy a 3D experience, franchises like Tekken, Soulcalibur, and Dead or Alive stepped into the spotlight. Even Street Fighter’s closest rival, Mortal Kombat, transitioned to 3D fighters. Despite the EX spin-off series’ use of 3D graphics, Street Fighter always remained steadfast in its 2D action. The final EX entry landed on PlayStation 2 in 2000, giving fans nothing more than re-releases of Street Fighter II and III on modern consoles in the succeeding years.

“People basically had forgotten about the genre,” Chen says. “While some franchises like Tekken and Guilty Gear continued to create quality games, other franchises like Street Fighter disappeared and Mortal Kombat had its notorious run of awful games during that period. Basically, in the U.S., fighting games were a thing of the past.”

However, as all its rivals trailblazed 3D frontiers, Yoshinori Ono, whose work with Capcom stretched back to the early ’90s, noticed how many people clamored for a new mainline entry. Based on the reception to Street Fighter II on Xbox Live Arcade, he petitioned Capcom’s Keiji Inafune to allow the team to create a new mainline game inspired by Super Street Fighter II Turbo.

Ono, who had previously worked as a sound producer on the Alpha games, stepped into the producer role as he tried to bring the series back to its roots. The result was Street Fighter IV, a game that used modern visuals and embellished 3D character models with ink-based flourishes instead of sprites. The team maintained the tight, responsive 2D fighting action that made Street Fighter so popular in the first place by implementing 2D hitboxes over the 3D character models.

Street Fighter IV landed in arcades in 2008, with home releases arriving less than a year later. The fourth mainline entry was a rousing success with fans and critics. By combining the classic gameplay and characters with beautiful visuals and new conventions, Street Fighter IV quickly became a modern classic and again ushered in a new era for the fighting genre. Though 3D games dominated the 2000s, the subsequent decade proved the importance of Street Fighter IV’s demonstration that enthusiasm still existed for the 2D segment. In the following years, several franchises – both new and old – embraced the 2D style once more, kicking off a renaissance for the genre.

Street Fighter IV continued to grow, with new versions releasing until 2014, ballooning the playable roster to 44 fighters. Ultra Street Fighter IV became a gold standard of the fighting game genre thanks to its diverse roster, a cornucopia of content, and tight gameplay. The franchise had bounced back from its biggest gap in compelling fashion, delivering one of the greatest games in the genre’s history. Street Fighter IV nailed modern gameplay while demonstrating fans were still hungry for classic gameplay, but it was time to evolve again.

That evolution came with Street Fighter V, a 2D fighter released in 2016 exclusively on PlayStation 4 and PC. The gameplay of Street Fighter V remained tight, iterating on what players experienced in Street Fighter IV while introducing moves like Critical Arts and V-Gauge moves. Capcom also laid out ambitious DLC plans including characters, stages, costumes, and more, but many criticized the game’s launch.

Early in its marketing, Capcom announced players could earn all characters for free through gameplay, but following launch, it became apparent it would require arguably unreasonable hours of play. Not only that, but the modes available at launch were barebones, with no Training mode, Arcade mode, or meaningful single-player story content. Even Ono, who executive produced Street Fighter V, and Capcom CEO Kenzo Tsujimoto, acknowledged the lack of content and polish at launch.

“There were a lot of things that they wanted to get done around the launch of the game, but they weren’t able to succeed in delivering all the elements and the features that they originally wanted,” director Takayuki Nakayama, who joined the project midway through development, says.

Capcom got to work addressing the criticisms. Before launch, it announced a post-launch update called “A Shadow Falls,” providing a cinematic story mode. The company launched this update for free in June 2016. In 2018, Street Fighter V: Arcade Edition delivered the long-awaited Arcade and Extra Battle modes and additional V-Trigger moves for every character. Arcade Edition was available for free as a title update to everyone who purchased the original game. Finally, in 2020, Street Fighter V: Champion Edition delivered sweeping balance changes, additional V-Skill moves for each character, and more. Champion Edition was also available for free to owners of Street Fighter V.

Street Fighter V course-corrected in many regards, but Capcom decided to move on from development before the original post-launch content plan could be fully realized. “Street Fighter V was originally planned to have six seasons, but then plans ended up changing, and we were told we could only make up to season four,” Nakayama says.

However, the community received Champion Edition so well that Capcom changed course again and announced a fifth and final season of content, which would serve as an endcap to the Street Fighter V saga and set the stage for what’s to come. Despite this shift, before the first content arrived, Ono stepped away from Capcom, ending a decades-long tenure.

Street Fighter V closed the book on its final season in November 2021, giving fans a glimmer of hope for what’s next. While it began its lifespan under heavy criticism, it ended with a robust suite of modes, a healthy competitive community, and more characters than any Street Fighter game before.

While Nakayama and producer Shuhei Matsumoto weren’t a part of the initial Street Fighter V development, they took various lessons from the launch and vowed to implement them in the next game. “Starting with Season 5, we changed the structure of the team,” Nakayama says. “And we learned that we wanted to take on a more direct communication style with the audience and players of the game. We received a lot of positive feedback about that. We realized that is very important for our audience.”

Street Fighter V served as a solid lesson for Capcom about what fans do and don’t like, and it showed that the publisher is willing to deliver on that fan feedback. With the departure of the man who fought to bring Street Fighter back to its roots in a time when nobody believed in it, the Street Fighter franchise was at a crossroads as it looked ahead to the future.

In 2018, Capcom began developing the next game in the series.

The last of Street Fighter V’s many DLC characters, Luke Sullivan, represented the road ahead for the series.

“Street Fighter 6 was in development during the tail end of Street Fighter V and rather than Luke being the final new character of Street Fighter V, we saw him more as kind of a guest character coming from the future,” Nakayama says. “At the time, we didn’t announce Street Fighter 6 yet, so we didn’t have the clear context behind who Luke is. It was a bit nerve-wracking. We wanted to make sure that we presented him under the correct light and were really excited but very cautious about that.”

Luke utilizes tactics he learned in the military to employ a specialized MMA style. But more importantly, he steps into the spotlight as the main protagonist for the next mainline game. That game is Street Fighter 6, which introduces loads of improvements, characters, mechanics, and features into the formula. This revolutionary next step in the series launches in 2023, seven years after Street Fighter V first arrived. To learn more about where the series goes from here, be sure to read our entire Street Fighter 6 cover story here.

This article originally appeared in Issue 351 of Game Informer.

Explore your favorite games in premium print format, delivered to your door.