The Virtual Life –Trying To Survive A Little Red Lie

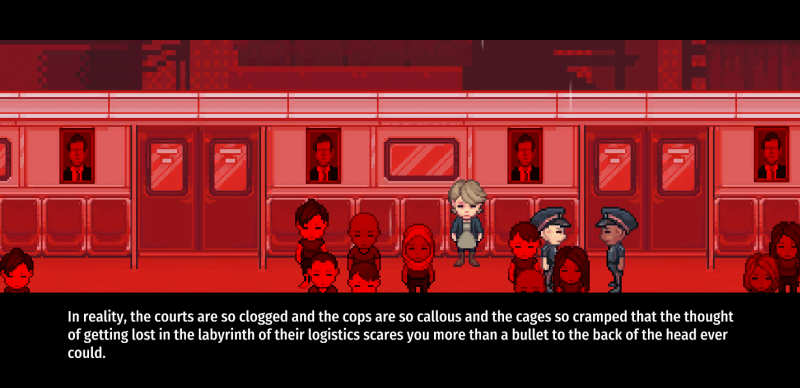

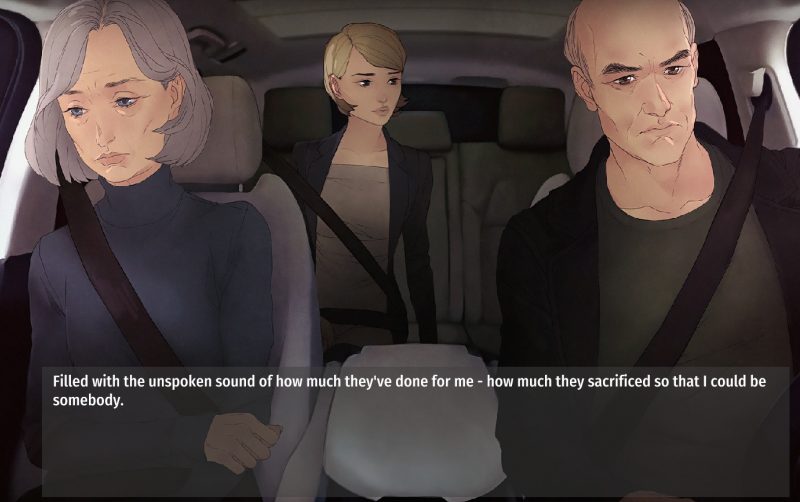

Little Red Lie is the latest release from Will O'Neill, who created Actual Sunlight, a narrative-driven experience that dealt with themes of suicide and isolation. Little Red Lie, which follows two characters as they navigate the mundane yet terrifying labyrinth of daily life in Toronto, is in much the same vein as Actual Sunlight but focuses on the weight that modern economics has on a person's mental and emotional state, relationships, and humanity. I played through Little Red Lie and found myself disheartened by the story and its bleak world, but captivated by the strength of its storytelling and brutal, unflinching gaze into despair.

I talked with O'Neill about his creative process, philosophies, and the merit of games as political art.

Javy Gwaltney: Both Little Red Lie and Actual Sunlight are despairing games with a bleak perspective on people trying to make it through modern life. Actual Sunlight deals with depression while Little Red Lie turns its gaze on the viciousness of capitalism. These games don't seem to allow for much hope. What informs these games and their brutality?

Will O’Neill: In both cases, I would say personal belief. I'd say the most optimistic thing you could say about either is that they express the idea that some kind of change is needed – that there's no future in going on the way things are as depicted in the games. In the case of Actual Sunlight, that would mean an unwillingness to confront your present reality, and in the case of Little Red Lie, it would imply an unwillingness to confront our collective future. I think everybody knows this – everybody knows there is no such thing as functional American capitalism in a world where nobody can be a truck driver or a cashier, for example – but there is a certain staring-into-the-headlights of it all that we just can't seem to escape.

We all know that the rich and the famous and important are going to bug out, cut and run as soon as things look really bad, but we keep buying magazines with them on the cover regardless. We all know all of these things – I don't see why a game shouldn't be unflinching about it. If anything, I'm disappointed with what I see as the false and misplaced optimism of so many others.

Do you think there’s no way out? Of the cage, I mean.

I think the funny thing is that we'll face a crossroads at which we could essentially construct a utopia of automation and technology, but only if it is shared. And that is when the same old monsters will stand up to say that they own it all, but that they're willing to lease it at generous rates. And then things go in precisely the opposite direction. And that is what I think will happen – but I do think that it could be different.

Little Red Lie, however, is essentially about how human nature all but guarantees it probably won't. And that is my perspective, absolutely. And it's ambiguous, morally, because so much of what inspires the bad action in Little Red Lie is family, and a loyalty to it. I mean, the intergenerational relationships themselves are an expression of that weird contrast – that the Baby Boomers have sort of screwed the generations that follow, but it's not like they're aliens or some invading force. They're our parents. Maybe they don't care about "us" in a broader perspective, but they care about you more than anything in the world. It's like you've got Boomers who are still working, because they need to make money for their unemployed kids, and yet those kids in a wider sense can't get a job because that Boomer won't leave it.

So I do hope that people will take away something more nuanced than simple doom and gloom from it all. Did you feel that aspect of it, or did you find it so overshadowed by the bleakness of it all that it was tough to cut through to that?

Yeah, I felt the tug of war aspect. These people care about you but at the same time...you eventually need them to give up what they can't give up. It's a very effective articulation of the human condition and generational strife.

That's good! I'm concerned that we're all rubbed so raw by real life now that harshness gets amplified, even in fiction. At the same time, I think it's the duty and entire purpose of art to be honest and speak from the heart. I would be doing a disservice to it to have done Little Red Lie any other way.

Right, I mean it’s terrifying to be alive right now, no? Missiles over Japan, economic despair. I often wonder what the role of political art in dire times is. Is it to try and effect change or to be a portrait of the times? Some mix of the two? Where do you think Little Red Lie, with its focus on capitalism and family and depression, fits into that equation?

I try not to not overestimate the power of art, no matter how much I care about it. Ultimately, if there is real conflict in our time and an upending of our political system, it won't be because people are inspired to seek love and equality for all – it will be because they have nothing to eat, no security of any other kind, and nothing to lose.

So I think art probably serves as a portrait and a record of the time, and it can inspire people – there are plenty of instances in recorded history where the first thing that bad people do is round up all of the intellectuals, artists and others who might articulate the truth in a persuasive way and silence them, one way or another. So there is definitely real power in words, and in art. But ultimately, if change comes, I think it will be real and material deprivation that truly drives it.

It's sort of a race to the finish, isn't it?

What do you get out of it all, as the creator of these games? Why do it?

I guess I find it satisfying to express something that I think is honest in the middle of a lot of dishonest noise. Aspirational pop culture is a never-ending symphony that beats on you all day, and Little Red Lie is that single triangle note that hits at the very end. It's tiny, but you hear it. And you know it's something different.

But I don't know if I'd even have an answer to that if someone didn't ask me directly. Speaking what you think is the truth and trying to express it in a way that is at least beautiful, however pointless, is something that I think justifies itself?

It's what being a writer or an artist of any kind is, right? You're doing it because you think it's real, and it means a lot to you. But Actual Sunlight was definitely a reaction to what I thought the pop-culture version of a guy like (depressed protagonist) Evan Winter was, and everyone in Little Red Lie is very much the same.

One of things I've noticed about both Actual Sunlight and Little Red Lie is that they're very minimal in terms of interaction. A lot of it is visual-novel text segments at points. I imagine a few questions people would have about these experiences are "Why are these games? Do they work as games? Why not a novel or short story anthology?" And I have my own answers to those, as someone who loves the medium, and is always examining how it uses interactivity in interesting ways, but what about you as the creator? Why should both of these be games as opposed to a more passive creative medium?

With Actual Sunlight, the interactivity was important precisely because it gave me something to take away from the player more and more as the game went on – as a reflection of the increasing myopia of the protagonist. You had little agency regardless, but when you lost what little you had, you felt it. In Little Red Lie, I use interactivity as a way of simulating directly the way I think we all process the lies we tell – that we think one thing but have no choice to say another. I think giving a tactile layer of action to that gives you a connection to the characters that you couldn't find in another medium.

But, of course, I also think there is just an inherent mechanical empathy that comes with moving a character on a screen, and literally walking in their shoes. That is definitely why I prefer the graphical style to working in something like Twine, as a lot of narrative-focused game developers do.

I think a lot of games beat their chest when it comes to interactivity by throwing so many actions at the player. Like, "Here's 47 different ways you can slit this guy's throat" or "Here's a major story decision that can have a dramatic effect on the ending," but sometimes it's nice to have interactivity draw attention to how powerless people can be, like the famous you're-damned-if-you-do-damned-if-you-don't binary decision at the end of GTA IV. Niko's screwed. He's always been screwed since he set foot in Liberty City because the systems are opposed against him and the people he loves.

Yeah, absolutely – I loved Niko's missions with the CIA / NSA stand-in agency more than anything, because he was finally working with a character who understood how foregone everything was. At one point the guy says to him, something like, "Just like in the old country" in Niko's language, and that was so brilliant. That encapsulated so much about that story. Loved it.

But yes – in most games, interactivity is used as a mode of empowerment. Level progression is a mode of empowerment. Achievements, trophies, everything: It's all a fantasy of being in control of your life and being able to succeed through skill and hard work. And the less of that people have in real life, the more attractive it gets in art.

And the less of that people have in real life, the more attractive it gets in art.

Let's talk about Sarah and Arthur for a bit. Like, Sarah is obviously sympathetic for a number of reasons (her poverty and love for her family) but I think Arthur, who's rich and disgusting and awful, ends up being the more interesting of the two characters because LRL asks us to try and understand this vile person. What led you to splitting the story between the two characters? Why focus on on that sort of character for half the game? There seems to be a lot of faith in the player to play as him for that long and not to bail when it becomes too much?

Yes, I think it's important that people do understand him, definitely, for the sake of contrast. What I was trying to show was that while you've got Sarah, who is out in the world trying to get by, making choices that matter, and having to live with the consequences of her decisions – even when they're unfair – you've got somebody else at the same time who is an endless ball of hurtling chaos.

But also one who, because of their money and stature and power, is able to effectively get away with all of it. And again, I felt like in a pop culture story, the character of Arthur Fox might be rich and evil, but he'd also remain erudite and clever throughout, to be Sarah's 'match' so to speak. But he isn't. He's just an ignorant, mean-spirited jerk with a drug problem and too much money. Absolute power that has corrupted absolutely.

And I think it's important that people see a character like Arthur Fox all the way through. You know, a thing about people like Rob Ford (or Donald Trump) is that it's all sort of funny, isn't it? Like, you hate these guys, but you feel like maybe you could have a drink with them (or at least before you could) or maybe they know a good dirty joke. But that's what they're like at arms-length. You don't want to be in the way of these people, or to have something that they want. It very quickly becomes a very different story. It wouldn't have been honest to write half of Arthur Fox – you have to write the whole thing.

So many times you have this archetype and there is something about them that feels, I don't know, very false. Like the Patrick Batemans or Gordon Geckos where they can talk their way into everyone's bed or pocket. And with Arthur there's something that feels grounded, like the muck is there because the player has a constant connection to his brain and it's ultimately very disturbing but compelling. You can see what makes him attractive to people but just how awful he is, is inescapable.

Exactly! Yes, I think you understand precisely. Several people have told me that their favorite character in the game is the bartender. She's one of the rare people in the game who doesn't need or want anything from Arthur, who doesn't exist in his social or professional milieu. I like her, too. And I also like the brief parts of the game where you control Melissa and Sarah's parents – that for a few moments, you get glimpses of how other people see the main characters.

Because for all her loyalty and better qualities, Sarah is definitely arrogant and superior – and you see that implied in her red text all over the place, but it's nice to get it from other people as well. And it's nice to see a bartender tell Arthur Fox to go f---himself.

It's a dense game. There's a lot there. Maybe too much. I think it definitely suffers against something like Actual Sunlight, which was very narrow in scope.

Did the expanded scope lead to things you're not happy with? Flaws that are in plain sight?

I mean, there are pieces of the writing that I like more than other parts, but I don't know about huge flaws in plain sight. Maybe the biggest flaw really is the length – I'm asking a lot of players to get through this, and I know it. At the same time, I'm not afraid to kill my babies. There were 5 or 6 entire scenes cut from the game. I don't think I could have made it much shorter than I did...!

And I think the other problem, as I've alluded to, is that I think it's very much against the zeitgeist. When I released Actual Sunlight, I felt like it was really well-received because there was a lot of interest in that kind of game at the time – certainly because of Depression Quest – but now I think people are generally looking for something more positive.

I mean, if Dream Daddy is the narrative hit of the summer, I think that says it all. Arthur Fox is no Dream Daddy. And I find that even narrative-focused games where I went in expecting horrific endings – Tacoma and Night in the Woods, for example – the endings are really quite upbeat.

They're inspirational, whereas with Little Red Lie, the most inspirational thing you can take away is that maybe, if we can make the world nothing like it is now, we'll have a shot. Oh, but we probably won’t.

Do you see yourself making more of these kinds of games, which are seemingly rooted in nihilism?

Yeah, absolutely. Because these games sell so terribly, I'm actually intending to make two more games with the existing art that I have now.

The first one is going to be about chronic pain, and the second one is going to focus on what people will probably call toxic masculinity, but which I will think of as the pretty sad story of the guys I grew up with. And the scripts for both of those are actually kind of half on paper and half in my head already, so I can promise you that there will not be another large gap in my output…god willing!

For more on games about hope and despair, check out The Virtual Life on Nier: Automata.