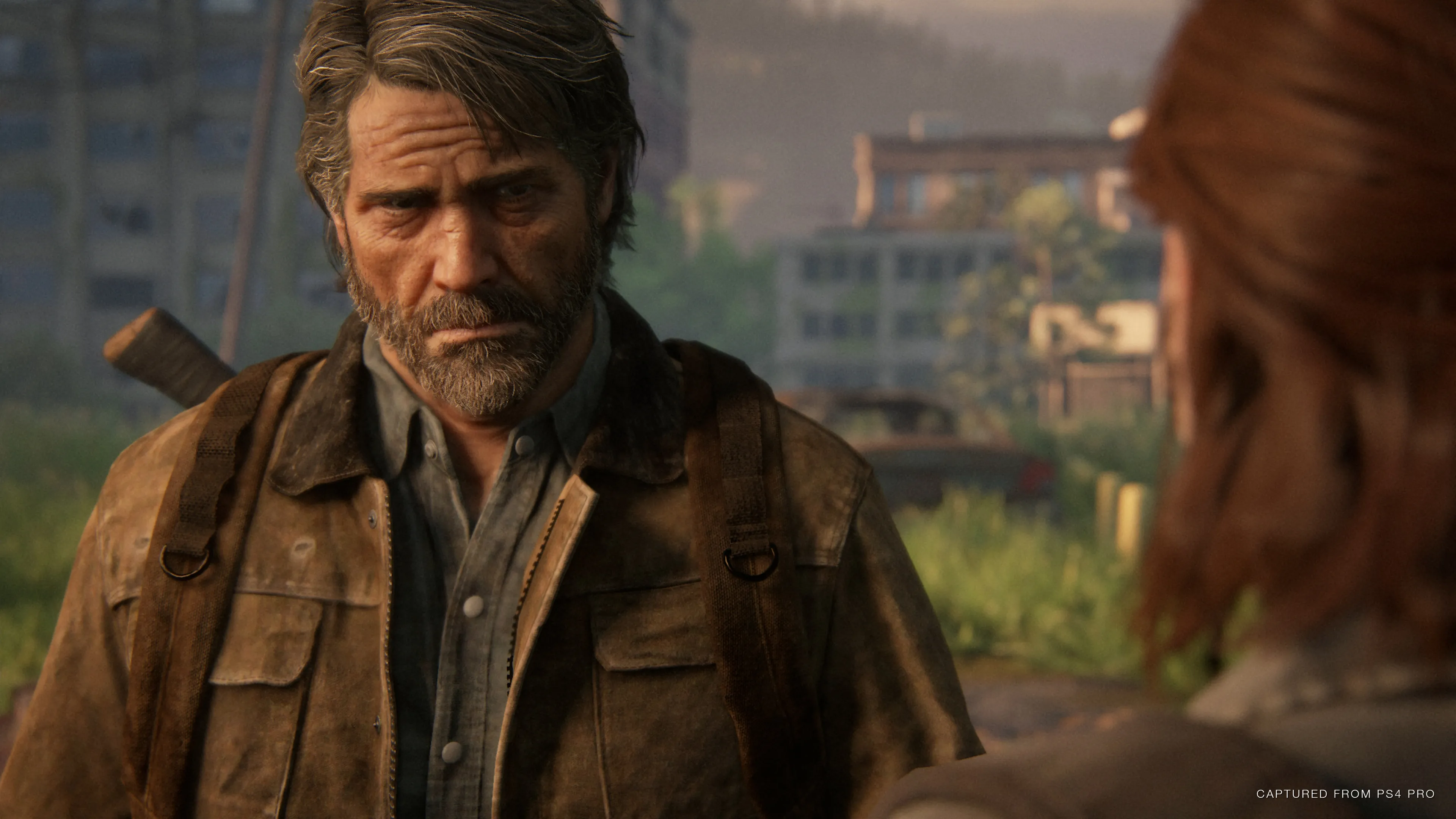

The Last of Us Part II

The Last of Us Part II is set in a post-apocalyptic world in which a mutated fungus has turned most of humanity into creatures called Infected. That premise may sound like familiar zombie fiction, but anyone who played the original can tell you that developer Naughty Dog has elevated the world of The Last of Us beyond easy genre classification. The story of Joel and Ellie was emotionally complex and raised ethical questions with no easy answers , and that doesn't appear to be changing for The Last of Us Part II. In advance of the sequel's impending June 19 release, we talked to creative director Neil Druckmann about how Ellie is evolving, being grounded versus realistic, and creating a believable world for players to explore.

GI: One of the earliest details about the story you revealed was that Ellie is on a quest for revenge. What do you see as the most fertile ground to explore within the themes of a revenge story?

Druckmann: When we started work on the game, there was an excitement to make Ellie the protagonist and to explore her character further – in the same way that I’m sure the people who worked on Breaking Bad were excited to explore Walter White for many years. We started with this girl who was so innocent in the first game, and we know this world is one that makes you make choices. As a survivor, you lose some of that innocence, shed it, evolve, and change. To take that further was exciting.

We played with ideas that were interesting from a plot standpoint, but never quite captured that emotional pull that we thought made that first game special. So then it was like, “Do we want to go back to this world if we don’t have that emotional pull?” We were starting to really debate that until we landed on this idea that felt like, “Oh my god, that’s almost like a mirror image. A mirror theme of what we had in the first game.” The first game was so much about love – can we, through the experience of a video game, get you to start with these two character who don’t quite like each other, and by the end of it, you get to feel the unconditional love that a parent feels for their child? And you understand how far that love can go, both in its beautiful aspects, and its very dark and almost insane aspects. So you understand why Joel does what he does.

In [The Last of Us Part II], it’s almost a similar question. How far would you go for love? Except the setup now is that the person you love has been hurt badly, and how far are you willing to go to bring the people responsible to justice? The motivation is still love. And when you look around the world, it’s stuck in this cycle of violence because the people they care about got hurt. And what do they do to the other side? How do they dehumanize then? How do they attack them? That all felt like fertile ground that raises the interesting philosophical questions that we had with the first game. It was like, “There’s the core. That’s the thing we’ve been missing. Now we can hang the whole story around this core idea.”

Revenge stories usually follow a formula – an inciting event, followed by going down the checklist of people along the way, and then a final confrontation. Do you think the established formula makes it harder or easier to surprise players?

You’re kind of describing genre, and almost every genre has already been told. Every kind of story has been told. When people say, “I’m telling a genre story,” that genre has been told a lot. There are certain tropes to it, and I think as a writer, it’s important to have an author’s knowledge of that genre – of all the different things that can exist in that genre. Sometimes, a revenge story can be a power fantasy, and you see the people who wrong the protagonist at the beginning of the game or movie or book, and it’s about the thrill of bringing those people to justice. The certain satisfaction, the cathartic release that happens.

And then there are ones – with maybe a more nuanced approach – that say, “There’s a cost to this. When you go and hurt someone else, even if you’re in the right, it takes something away from you.” There’s a primitive part of our brain that wants to tip into that, but whether through society or evolution, we suppress it so we can live normal lives. I think if you give into that, sometimes it changes you irreparably … and then to make a character-driven experience where every mechanic that we’re building puts you the shoes of Ellie and you feel the evolution of that character as she becomes more lethal, but also as she’s losing more of her innocence, it begins to affect not only her, but the people around her.

From a storytelling perspective, how often do you struggle with what needs to happen in service to the story, versus what you want to happen? Like, do you ever just want to give Ellie or Joel a break?

I think that wouldn’t be The Last of Us if people just got a break. That’s not what the story really explores. It explores the beauty of relationships, and the horror of relationships. It deals with the bonds that get formed, and relationships that fall apart, whether that’s through injury, death, or people just growing apart. Those are kind of what’s ripe for exploration with The Last of Us. But how do you explore all those facets and philosophical questions? I think what made the first game successful was that it presents ideas, and the characters have strong feelings about those ideas – or dilemmas – but the story doesn’t. The story doesn’t judge; it doesn’t say Joel was right or wrong. Joel feels righteous. I’m sure the Fireflies feel like he wasn’t.

Likewise in this game, Ellie feels righteous, but I’m sure the people she’s doing this stuff to don’t agree. So much of the story is about empathy and trauma. And sometimes feelings that are unique to video games, like guilt and shame – can we make you experience those things through the actions you are taking part in? You are complicit in what’s going on in the story when you’re taking part in it. And that became exciting, like, “How far can we push those ideas?” Can we push the wall of the kind of story we tell at Naughty Dog, but even as an industry? If we can pull it off, it will feel like something I have never experienced in a story, and especially in a video game. It could be something really special.

You’re telling a story, but you’re also making a game that people play. That means players might see a disturbing and brutal cinematic one minute, and the next they’re scrolling through skill trees spending medical supplements to buy skills. How do you approach that tension between game elements and story elements?

That’s where it’s important early on to establish: What is the vision for this thing? We knew we wanted to put you in the shoes of Ellie and take you on this really long journey where each death has weight and consequence … Exploration has meaning to it … And then one of the things with The Last of Us more than other games we’ve done is that it needs to be grounded – despite there being Infected and the state of the world. How can we make you feel like a character is like someone you know? That doesn’t always mean realism, one-to-one. Like, you’re describing mechanics that don’t exist in the real world – crafting things, leveling up and improving attributes. But what those systems do is they make you feel the growth of Ellie as a capable killer, which speaks to the story. Sometimes you’ll give up realism for the sake of getting a certain feeling. Something I’ve discussed in the past is: With Ellie’s size, it’s not realistic that she could take on as many people as she does. We want every encounter to feel engaging, and make the enemies feel smart – but the reason we have the numbers we do is because it creates a certain feeling of survival and tension. If we were to lower the numbers, you wouldn’t get the same feeling. So we’re sacrificing some realism for authenticity of feeling.

So, once you define those constraints – I have the privilege of working with some of the most talented people in the industry, and they are constantly coming up with great ideas. Often, we have more ideas than we can fit in a game; you have five people coming up with five ideas that are all great on their own. Sometimes you might not go with the greatest idea – you need to go with the idea that’s most appropriate for the game. So once the vision is well-defined, people can go off on their own and come with ideas they think is appropriate for the game. And that’s kind of the beauty of video games – it’s such a collaborative medium, it becomes greater than any one person’s contribution. And we’re all working with the same goal of achieving a particular feeling.

The places players explore, like shops and restaurants, are incredibly detailed and unique. Can you walk me through the process of creating an area?

We first come up with the structure of the game, the core story idea. And then we start putting notecards up on the wall representing each section or level – whatever term you want to use. Then we break down what is happening narratively in the scene. How is the character changing? Every part needs to evolve and take us toward the end – no part should just exist because it’s cool. We want cool ideas! But they have to work toward what we’re trying to move forward. If they’re just cool for the sake of being cool, that’s the first card that gets tossed.

For example, when you first reach Seattle, we want Ellie to feel a little frustrated, a little lost. We do that by – based on stuff we did with Uncharted 4 and Lost Legacy that let us play with a much bigger level size than we have in the past – we create a really large space. We put you in downtown Seattle. You don’t know where to go. The character doesn’t know where to go. We want you to feel lost and start moving around. Again, authenticity is what’s going to help immerse you. If you’re moving through a space that doesn’t look good, that doesn’t look believable, it’s going to pull you out of the experience.

The art team traveled many times to Seattle to study architecture, the materials, the vegetation that grows in that part of the country. That kind of detail is going to immerse you in the world. Likewise, our tech team has to find a way to optimize it on the PS4, because again, if the level of detail drops because the area is big, that takes you out of the experience. Everything is in service to put in you that place, evoke a certain emotion, and put you on a journey with Ellie.

You’ve previously mentioned the Last of Us Part II broadening its narrative focus beyond Joel and Ellie. When you look at The Last of Us as a property or franchise, how much do you see it as the focused story of particular characters, and how much is about the world they inhabit?

Yes. [Laughs] Meaning, when we finish a game, our process is to look at every idea on the table. It might be an idea for a sequel [to that game]. It might be an idea for a sequel to an old franchise we haven’t touched in a while. It might be ideas for new IP. Everything gets explored, and we exhaust all of the ideas, because you’re going to go on this journey for many, many years. You want to make sure you pick something you’re really excited by, because four years into it, you’d better be as excited as you were at the beginning. Otherwise, if it’s something you’re ho-hum about, players are going to feel that. They’re going to feel your lack of excitement.

So, for The Last of Us Part II, it was exciting to come back to Ellie and explore more facets, more dimension to this character. Other ideas that didn’t have Ellie and Joel became less interesting – building characters from scratch or going to another part of the world. We talked about them. They just weren’t as exciting … But there were a lot of questions early on, like, “What is The Last of Us? Is it Joel and Ellie? Is it a particular set of themes?”

We knew we wanted to continue the journey of Joel and Ellie pretty early on, and then you need themes with an emotional core to ask philosophical questions – that became another pillar. The other thing we said was that we want to explore factions and how different people survive. Now we’re 25 years after the outbreak – what are they doing to form societies? And how do those societies speak to the high-level theme? Here we’re dealing with a cycle of violence, which is why we’ve crafted the WLF and Seraphites – groups that are locked in this everlasting conflict trying to reclaim Seattle … Everything has to speak to these high-level themes. And there’s just the Naughty Dog value: We want to challenge ourselves. We want to tell stories that we’ve never told before. We want to push the boundaries of the technology. We want to figure out pipelines of how to build games more efficiently. And – this shouldn’t be controversial, but it is – we want to have a diverse cast of characters that reflects the world we live in and helps us tell more unique, interesting stories. Those are things we value that come back into the game as well.

The original Last of Us enjoyed pretty widespread acclaim, but it wasn’t without criticism. Was there a particular piece of feedback from the first game you wanted to be sure to address for the sequel?

Pallets and ladders. We knew even when we were working on the [first] game that we wanted a wider breadth of mechanics, and we wanted those mechanics to go deeper. That’s one of the challenges we set for ourselves for this game. The challenge there is that The Last of Us isn’t a sci-fi world where you can have a gravity gun or grappling hook or something that is easily marketable, like, “Here is the brand-new feature.” So it’s really the sum of the parts.

Going prone might seem simple on paper, but with the fidelity we have, how intricate the layouts and art are, and with all the mechanics Ellie can do while prone, it’s a hugely complicated system to look as good as it does and be as effective as it is. Likewise, adding grass that looks good, as well as the effect it has – you’re also not completely hidden, so it’s the idea of analogue stealth – creates a level of tension that would be different if it was black or white, hidden or not. Which again, is a complicated system. Redoing our A.I. where they have vision and hearing. Every person has a name, every person has a heartbeat that is being tracked, which affects their audio cues – they might breathe harder or shout more. They have an emotional state that can change if you kill their friend next to them. Again, it’s a lot of small – “small” – things that, when you play it, hopefully you’re feeling much greater tension. Because Ellie can jump, climb, and we have better physics, the puzzles become more interesting. The exploration becomes more interesting. All of that, again, is done in service to putting you in the world, giving you more variety, and giving you more depth of mechanics.

You mentioned marketable features. Let’s say we lived in a world where it wasn’t necessary to have things like trailers and gameplay demos prior to release. Would you prefer to just set a date and launch the game, or is it fun to build the mystery?

I’m trying to imagine a reality where you don’t have to market your game. [Laughs] I think I have a pretty good imagination, but that’s a really hard one. I think there’s something that is exciting, especially when you work on something for so long and you have to be secretive, about moments where you’re like, “Okay, we’re going to show some of the game.” There’s something different about internal deadlines and external ones. External deadlines, you know the public is going to see it, and this pressure starts building. All of sudden, you’re making all these calls; you might have been doing all this exploration, and it helps you just lock some of the game down.

When people react positively, with conversations and excitement around it, you can just feel that energy on the team. You walk around and you can feel it from people, “We’re doing the right thing. This thing that has been super-challenging that we might have had doubts about, it feels like it’s clicking and starting to work.” Those are things that would be hard to give up.

But there’s something nice about trying to preserve the experience. That’s the push and pull: Trying to reveal as much possible without spoiling the final experience. But at the end of the day, nothing can spoil actually getting your hands on the controller, playing as Ellie, hearing the dialogue, seeing how the mechanics are adding to the tension of the world, and experiencing those beats.

For more on The Last of Us Part II, read our impressions from two hours of hands-on time with the final version of the game.

Get the Game Informer Print Edition!

Explore your favorite games in premium print format, delivered to your door.

- 10 issues per year

- Only $4.80 per issue

- Full digital magazine archive access

- Since 1991