Our extra-large special edition is here. Subscribe today and receive the 25% longer issue at no extra cost!

Gazing up at the orange Carrot building in Setagaya, Tokyo, you would have no idea it was the home of Game Freak, the developer behind one of the world's most popular video game franchises. The Pokémon logo isn’t displayed anywhere in the lobby, and Pokémon Go’s nearby PokéStops don’t offer any hint of the studio’s existence. Across the street at a 7-Eleven, a banner waves over the door to promote the most recent Pokémon movie, but that’s currently at every one of the convenience stores throughout Japan.

Once you make your way to Game Freak’s floor, a red sign with the company’s logo makes an appearance in the hall, but you won’t see your first Pokémon until you make it past a locked door. The waiting area is a dark room with a single chair, ominous floor lighting, a backlit Game Freak logo, and a brightly lit, slowly rotating globe.

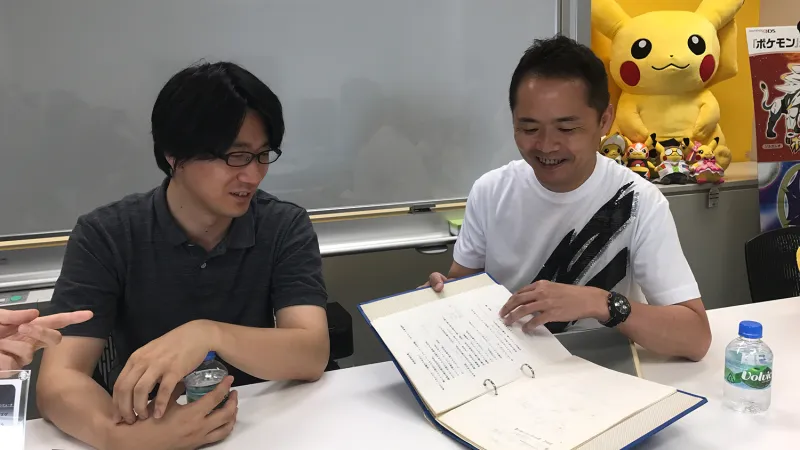

Junichi Masuda, Game Freak’s co-founder and Pokémon’s longtime programmer, producer, director, and (perhaps most famously) composer, lets us into the studio and tells us the globe in the lobby serves as a daily reminder of Pokémon’s global reach. We take off our shoes to walk through the studio, which Masuda says is done to make the environment feel as comfortable and as close to home as possible, especially since Game Freak's first office was in someone's house.

The development floor is open with few sectioned-off offices, and Pokémon plushies are scattered everywhere. Masuda shows us the meeting rooms, each one specially designed by the staff. The Gaia room has a large fish tank and is covered with plants, which the staff takes care of themselves. Masuda says the staff tends to them as a way to remind everyone about the long-term rewards of incremental work. “It’s just like making a video game,” he says. The nearby Saturn room is filled with mirrors that draw your attention to a large television. This room is used when they need to present something on screen.

The most interesting room, however, is the Venus room, located just next to the studio’s common area. It feels like the bedroom of a young girl, with pink walls and a chandelier hanging from the ceiling, which Masuda does not immediately dismiss as being the inspiration for Chandelure. We take a look at the heart of the development floor, a casual meeting area filled with toys and board games neatly arranged on shelves, before moving to the Jupiter room. This extensive area serves a museum of sorts for Game Freak, with copies of all of its games in glass cases, a collection of neatly arranged Pokémon plushies, a stack of every console you can imagine in the opposite corner, and miniature figures of every single Pokémon – they think. More than 800 different Pokémon exist in the games, so you can’t blame them for being unsure.

Game Freak's Beginnings

Before Game Freak even thought about merging "pocket" and "monster" into a single word, it was a print publication focused on covering Japan’s arcade scene. Headed by Satoshi Tajiri, credited as the creator of Pokémon, Game Freak the mini-comic (as Masuda refers to it) would interview arcade owners and get tips for playing popular arcade games. During this time, Tajiri met Masuda, and the two became fast friends.

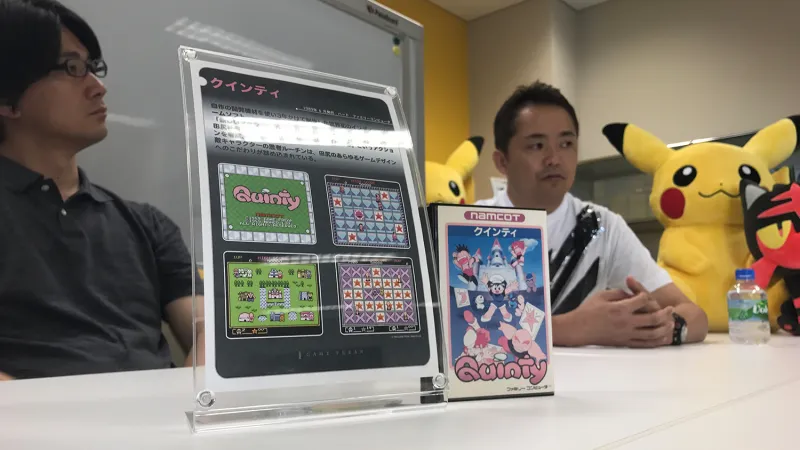

“The Famicom system released in Japan, and video games in the home were starting to become a thing,” Masuda says. “We knew we couldn’t create an arcade game, but if it was on the Famicom, we knew we might be able to do something ourselves.” Tajiri and friends got to work on a game called Quinty, which would later release in America as Mendel Palace. Bandai Namco (called Namcot at the time) would eventually publish the game, but only after Game Freak became a formal company. Namcot representatives told Tajiri they wanted to form contracts with companies, not individuals. “When we first started making the game we didn’t really have any official development equipment, so we just sort of had to hack the Famicom and figure out how it worked so we could develop on it ourselves without the official development tools,” Masuda says.

At this stage, Tajiri was already talking to Nintendo about making games, but it wasn’t until Nintendo offered Yoshi, the 1991 puzzle game, to Game Freak that the relationship became official. Yoshi was successful, which lead to a mouse-based Super Famicom game called Mario & Wario that never released in America.

Tajiri continues to be an important part of Game Freak, but he is less hands-on with game creation. Masuda handles the creative side of development today, producing and directing the majority of Pokémon’s major releases. “[Tajiri] really serves the role of executive producer on all of the games. Depending on the project he will look at the game and be more hands-on, but a lot of his time is spent researching various media forms,” Masuda says. “When it comes to running the company and doing game development and press interviews, he just kind of leaves that up to me.”

How To Make A Pokémon Game

After a few successful projects with Nintendo, Game Freak showed Nintendo the earliest ideas and versions of Pokémon, created on development units that Nintendo was essentially letting them borrow. “With Pokémon, we were just kind of making it ourselves at first. We did present the game concept to Nintendo and they said, ‘Oh okay, good luck. As long as you guys have money, keep working on it.’” Masuda says with a laugh.

Game Freak wasn’t sure exactly what the game was meant to be from the beginning – one of the reasons for its lengthy development cycle. Game Freak knew the focus was on catching monsters, and that there would be lots of different kinds of monsters, but everything else was a matter of trial and error -and -experimentation.

The earliest concept was an emulation of catching bugs, and that hasn’t changed much over the years. “Kids don’t really catch bugs much these days, but yeah, that concept of going out into the wild and catching something, fish or crickets – that’s still something that we want to pay care to,” Masuda says.

Every game is different, but today, a new Pokémon game begins development with a central theme and design. “What kind of experience do we want players to have? What kind of new connectivity features do we want to input into the game, or new gameplay modes? We think about those things,” Masuda says regarding where development begins. Other elements like the story and location come later. “I think a lot of people think that it comes from inspiration of the places I have visited, but that’s not necessarily the case,” Masuda adds. “A lot of it really comes back to how we want players to play the game and have the experience, and we look at what region in the world will match that best and what would express that the best.”

How To Design A Pokémon

The other important piece of a Pokémon game – next to the world, story, and mechanics – is the Pokémon themselves. Each generation of games adds new monsters to the collection, which now features over 800 creatures. “The graphic designers are obviously going to be the ones finalizing the look, but it’s not just the graphic designers who come up with ideas or draw the Pokémon,” Masuda says. Sometimes new Pokémon come about as a product of someone wanting to see a specific animal represented, or the battle designers might want to see a specific attack that requires a new monster, or the story writers might need a new type of Pokémon for a specific story beat.

“There aren’t really hard and fast rules of things you can’t do, but one thing we always pay attention to is treating them like living creatures,” Masuda says, “When designing Pokémon, and not just from a graphic-design perspective, there must be a reason for why it looks the way it does, and you have to think about why it might live in the Pokémon world.”

A Pokémon design getting axed late in development is rare. “Ideas don’t get thrown away very much, it’s more just feedback, like wanting to change them a certain way,” Masuda says. “With 20 years of history, at this point everyone working here has a good idea of what a Pokémon is, and what it should be in a shared sense. It has become a lot easier to make designs that work these days.”

In 2016, Pokémon celebrated its 20-year anniversary. The series has held on strong during this time, maintaining its popularity and commercial sales, even in the face of waning fads. The games all share a familiar core – catch Pokémon, train Pokémon, get badges – but each subsequent entry brought something new to the franchise. Game Freak co-founder Junichi Masuda and Shigeru Ohmori, who has been with Game Freak since Pokémon Ruby and Sapphire and directed Sun and Moon, went through each individual game to share their memories.

The original Pokémon that started it all. Released in Japan as Red and Green, North America traded the Green version of the game for Blue. Development lasted for six years, and was slowly chipped away at while Game Freak worked on other projects like Yoshi, Pulseman, and Mario & Wario.

“[Shigeru Miyamoto] was actually one of the people who suggested doing two versions of the game,” Masuda says, “Even if we were to have that idea here at Game Freak, we would have assumed there was no way they would produce two versions of a game. They just wouldn’t do that.”

Even as an unproven property, Game Freak was certain it had something special. “We knew it would do well, but it wasn’t until we saw a lot of people in the media writing about it and covering Pokémon – like seeing it in magazines and newspapers – depicting the phenomenon [that we knew for sure.]” Masuda says. Today, it doesn’t take long to get feedback about the success of a game, but in 1998, Game Freak was mostly working in the dark.

“We weren’t getting tons of reports from Nintendo about how it was selling. We could see people out in the parks playing Game Boys and exchanging Pokémon. Every time we would go to a store, it was always sold out no matter how long time went on,” Masuda says. “It was about a year after the game came out that we really started to realize it was turning into something pretty big."

Other indicators of the game’s success came from surprising avenues. Masuda remembers hearing the game’s iconic ball-capture sound effect appearing on Japanese television with no connection to the game whatsoever. It was also around this time that the anime premiered on television, which was a success in its own right. “We definitely watched it together,” Masuda says, even if Game Freak was hesitant about some of its ideas. The anime’s production company, OLM, Inc., was the one who identified Pikachu as the face of the franchise early on. “[OLM, Inc.] showed us a clip of it and we listened to the sound of [Pikachu] saying its name over and over in a really cute way and we weren’t really sure about it,” Masuda says. “But it worked out.”

Work quickly picked up on creating alternate versions of the core game, though it was more a matter of experimentation rather than trying to strike while the iron was hot. In Japan, Blue came later, and was initially only available as a special mail-order game. Yellow, on the other hand, saw wide release and tried to incorporate some of the anime’s success. “It wasn’t like we had development docs all prepared in advance, it was just a lot of experimentation,” Masuda says. “We were still kind of hobbyists at the time. It was kind of like when you make food and you’re like, ‘Let’s try another dish!’”

Game Boy was always the destination for the game. Game Freak was familiar with developing for home consoles, and the Nintendo 64 was on the horizon when Pokémon first launched, but the ability to trade kept the game on a mobile platform.

“We really couldn’t consider any other system, because we knew we wanted the link cable for trade. We were just focused on that cable facilitating trading, and during development we didn’t even have link battles,” Masuda says. “There was an automatic battle feature that you could do with connecting, but we were focused on trading. Near the end of development, we figured out a way to get battling working.”

The success of these first games is staggering. They sit comfortably in the top 10 of the best-selling games of all time list, and edge out The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim as the best-selling RPG of all time.

Even with all these achievements, as development ramped up for its next project, Gold and Silver, Masuda and Game Freak still felt like hobbyists playing around with their programming tools. “It was a much more gradual process that we kind of changed the development style to more planning up front,” Masuda says.

Despite the massive success of Pokémon, Game Freak struggled with the development of Gold and Silver. The studio was feeling the effects of a six-year development cycle.

“After Red and Green came out, and the follow-up games, we didn’t have a lot of money. We were kind of out of money at that point because we had spent all the development funds and everything, so we needed

to make some other games to stay in business,” Masuda says. Masuda worked as a programmer on a game that never released in America called Bazaar de Gosāru no Game de Gosāru at the same time he composed music for Gold and Silver.

When he moved over to Gold and Silver full time, the game wasn’t where it needed to be. “Development wasn’t going as well as we had hoped it would. At that point I kind of took over and we decided to make the game based on Kyoto, and we sort of rapidly developed the game [from that point on],” Masuda says. “We still didn’t have a formal development style at the time. It was a more gradual process.”

Despite the financial and development issues, the game’s scope was never scaled back, for better or worse. “That was all of us just trying our best, I guess,” Masuda says with a laugh.

The game didn’t have its setting locked down until Masuda joined. All that was in place were the names Gold and Silver. Masuda wanted the games to reflect old Japanese cities, and started researching the regions of Kyoto and Nara. “I knew I wanted to focus on towers, and those cities had those old kind of Japanese towers and that’s where the inspiration came from.”

Masuda recalls riding in a cab around the region talking to drivers to learn about the Toji tower of the east, and the sister tower to the west that had burned down. “In that sense, it was a different approach for what we did in Red and Green, caring about the setting,” Masuda says.

Satoru Iwata, Nintendo’s late president and CEO, was important to the development of Gold and Silver. He worked on making sure the localized versions were ready for release by analyzing the game’s code – not a task typically done by an executive. “That guy was a genius, “Masuda says. “Even with Red and Green, he asked us to show him our source code, and within three days, he probably knew it better than we did [laughs].”

Gold and Silver famously includes two regions: Johto, the new region, and Kanto from Pokémon Red and Green. “With Red and Green, this material was still back when it was running on a two-megabit cartridge,” Masuda says. “Halfway through development we upgraded to a four-megabit cartridge, and as programmers were like, ‘Oh my god! Double the space!’” That freedom in size allowed the game’s scope to double.

At the time of release, Gold and Silver held the rare achievement of being the fastest-selling games ever.

Ruby and Sapphire marked Pokémon’s first true platform change – the first of many to come. For Masuda, it also proved to be the most difficult to develop.

The screen size changed, more colors were available, and it generally gave Game Freak more creative leeway, but also substantially inflated the work load. None of those issues, however, compared to the outside perception of Pokémon at the time, and it weighed heavily on Masuda.

“After Gold and Silver came out, they were a huge hit around the world. Everyone was saying, ‘That’s it. The Pokémon fad is over! It’s dead!’” Masuda remembers. “We at Game Freak took that as a challenge and said, ‘It’s not dead. We’re going to show you guys you’re wrong!’”

At the time, Masuda says there was no faith in the Pokémon brand to maintain its popularity, and he could feel it. “Pokémon Go is experiencing something similar where people are saying, ‘Eh, it’s done. The fad’s over.’ But it was way worse than that after Gold and Silver.” Masuda remembers seeing Pokémon toys getting marked down in stores, and coming to America to see Pokémon merchandise – both official and unofficial – start to fade away. “The next time I visited, it was all Star Wars. Everyone was saying [Pokémon] was on a downtrend, and I really felt that pressure to make something amazing.”

Before development of the series’ next entry began, Masuda was already planning out Pokémon’s long-term goals. Game Freak would create Ruby and Sapphire, follow up with Diamond and Pearl, and between those games, would remake the original Pokémon games as FireRed and LeafGreen. “I had this three-game span in mind already, but then midway through it, we were doing trademark research, and the issue came up that maybe we can’t use Ruby and Sapphire. This whole plan of mine relied on this game being Ruby and Sapphire, and moving on to Diamond and Pearl,” Masuda says. Game Freak had started recognizing the game as an international brand, and was trying to make sure these new entries could be launched globally with as few issues as possible. “I got really stressed out and had to go to the hospital with stomach issues, and had to get a camera inserted. They didn’t know what it was – very stressful.”

Masuda based the game’s region on Kyushu, which he describes as a very vertical region of Japan. “I stretched it out horizontally, and poured everything I had into it to make it the best game possible,” he recalls. “The night before release I had a dream that it was a complete failure, a total nightmare. The morning after, the day of release, I went into the local shop, and saw people lining up to buy it and was extremely relieved. It was close. Super scary at the time.”

Ruby and Sapphire went on to be huge successes, breaking a sales record in Japan previously held by Final Fantasy X, which hit the year prior.

FireRed and LeafGreen marked the first of many Pokémon remakes for Game Freak. The main reason to rerelease the game was to make sure every Pokémon could exist within a single generation, and ensure the classic Pokémon would have a place on the most modern versions of the games, since they couldn’t be transported from the Game Boy titles to the new Game Boy Advance games.

“We talked with Nintendo over and over, trying to figure out a way to do that, but there was just no way to technically facilitate that communication.” Masuda says.

Of course, that wasn’t the only factor. “Really, just having so much attachment to the original Red and Green games, they were very special to us at Game Freak, and we wanted to recreate that and allow people to experience them again.”

Game Freak has already remade six of its previous games and looks to continue to do so with more games from its backlog. “I don’t think we’re focused exclusively on making all new stuff. I think it’s important – the nostalgia factor is one thing – to give these memories, this content, another chance to shine for new players. And as a player myself I enjoy that kind of thing, as well.”

As remakes, LeafGreen and FireRed didn’t quite reach the commercial heights of the Pokémon games that came before them, but they had no problem selling 10 million copies.

Diamond and Pearl brought an extra screen to Pokémon, but they also introduced another important innovation: online connectivity.

“Two screens is really tough to work with,” Masuda says. The DS was a new gaming frontier at the time, and the most important thing for Game Freak during development was making sure new players understood how the screens were used. “A lot of the things we focused on were to make sure that if someone who didn’t play a lot of games, would they think to touch that screen? We focused on making sure people wanted to reach out and touch things. That’s how we designed the interface on the bottom screen. Making them look like buttons.”

It was also important to Game Freak to make sure the game could be played with your fingers, and not just with the stylus. “I don’t want to speak poorly of Nintendo, but when the DS first came out they had fully expected, and they were always telling me, ‘Everyone’s going to play using the touch pen,’” Masuda says. “But later when I saw all these kids and other people using their fingernails and fingers to play the game, it seemed like most people were doing that.”

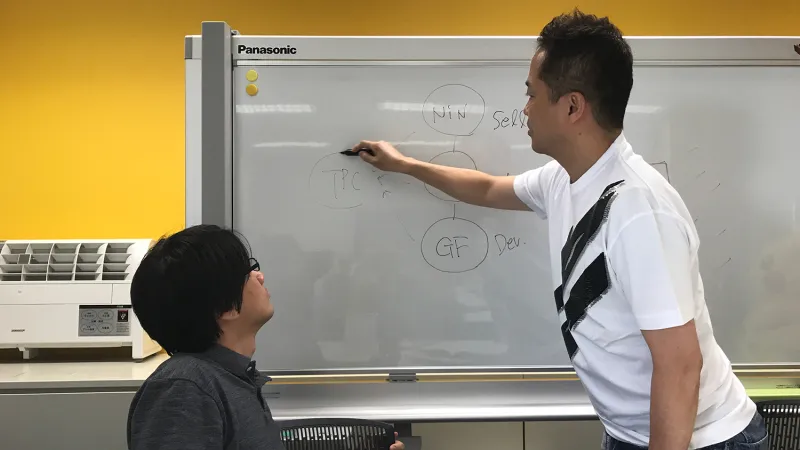

Bringing the game online for the first time also proved challenging, mostly thanks to the localization process. “We kind of created rules there with the Japanese characters you would have a certain amount of given characters, and you would double that for the Western languages,” Masuda says, as he writes out a collection of letters on a whiteboard behind him. “Pokémon in Japanese could only use five letters so the English version could use 10. We had to think about the widths of all the different interface pieces and how they would appear. So, for each Japanese character you could have two Roman characters.”

The first games on DS were, unsurprisingly, huge successes in their own right, but they also helped boost DS sales dramatically. Nintendo estimates that nearly half a million additional DS handhelds were sold to players who wanted to play Diamond and Pearl.

The remakes of Gold and Silver were straightforward re-imaginings of the hugely popular Game Boy titles, but they did add a new element – one Nintendo would return to for the 3DS’ built-in pedometer – in the form of the Pokéwalker.

The idea for the Pokéwalker, which would be included with every copy of HeartGold and SoulSliver, actually came from Nintendo, and Ohmori was the one who took it and developed the mechanics. “I added a lot of gameplay ideas, like being able to take your Pokémon out for walks. Based on the number of steps, something good would happen, and then you could take it back into the main game,” Ohmori says.

Similar to the previous remakes, FireRed and LeafGreen, HeartGold and SoulSilver didn’t sell as many copies as the original Pokémon entries, but the games were still the top-selling titles of their release week, and went on to sell more than 10 million copies.

Black and White marked some important innovations for the series. They were the first to use fully animated Pokémon character sprites during battles and experimented further with 3D elements. Cities were rendered with the new 3D engine. Black and White also introduced 156 new Pokémon to the series, a record for most new creatures that was previously held by Red and Blue’s original 151 Pokémon.

“With the Black and White games, we really wanted to express this feeling of variety and diversity and different things kind of existing in the same place with people and Pokémon,” Masuda says. “When I was thinking about that, the first place that immediately came to mind was Manhattan in New York. There you have all these people living together in one space, but when you look at it from afar it appears as one. We expressed that with the Japanese name, Ishu Region, which means one type, which is one way to say it, and Unova, ‘uno,’ which is kind of a similar idea in English.”

Black and White’s success is notable, as they were the fastest DS games to sell 5 million copies at the time.

To date, Black 2 and White 2 are the only Pokémon games that are true sequels to the games that came before them. “Near the end of the development of Black and White, the team was coming up with ideas of what we would do next and a lot of them felt like they really wanted to expand on the story and the world of Black and White,” Masuda says. “So, the idea came up – what if we did a game that was set a couple years after Black and White wrapped up to kind of show how things changed and expand on the events of the previous one?”

Along with it being a continuation of the lore, the game also had two versions (unlike the follow-ups that came before it like Yellow, Crystal, Platinum, etc.) and released two years after Black and White. “The number two just kept popping up,” Masuda says. “We thought, ‘Why don’t we call it Black and White 2?’ which is pretty much how the title came up.”

“A lot of people were expecting Pokémon Gray at the time, but the concept of Black and White was kind of these opposing forces – a yin-yang kind of thing,” Masuda adds. “If we went with Gray, it would have moved away from that concept so we decided to keep the titles there.”

Even though they are among the weaker Pokémon games in terms of sales, Black 2 and White 2 were still highly popular, with more than 7 million copies sold.

Alongside another platform change, going from DS to 3DS, X and Y marked the series’ biggest graphical leap. Diamond and Pearl, Black and White, and their sequels flirted with 3D elements, but X and Y went all in. It wasn’t the first time Pokémon had been rendered in 3D, but it was the first time they would be in a core Pokémon RPG. Prior to X and Y, Creatures, which manages the card game, had been making 3D models of assorted Pokémon. “We went to Creatures to talk to them and pick their brain about the process of making Pokémon 3D models, and what you need to care about,” Masuda says.

Despite the stereoscopic capabilities of the 3DS, Game Freak used it sparingly, preferring to use the 3DS’ full processing capabilities over displaying certain images in three dimensions. This went against what Nintendo wanted developers to do with the system, but it wasn’t a problem according to Masuda. “[Nintendo] always wants us to use as many of the hardware’s features as possible, but after just talking with them and explaining our thoughts on it, it worked out.”

Pokémon, in general, comes to Nintendo’s platforms late, which afforded Game Freak the opportunity to see how people were using the system’s 3D capabilities. “I did have it in the back of my mind, maybe people won’t constantly be using the 3D feature by the time this game comes out, but there was another factor,” Masuda says. “Nintendo officially was recommending that kids under six not use the 3D feature, and we wanted younger kids to be able to enjoy the games just as much as the other players.”

Thanks perhaps in part to embracing the first generation of creatures and its move into 3D, Pokémon X and Y was a massive success and is the 3DS’ best-selling game.

Despite the difficulty of developing Ruby and Sapphire, a game that literally put Masuda in the hospital, Game Freak decided they were next for the remake treatment after developing X and Y. For Ohmori, revisiting Ruby and Sapphire was a nostalgic experience as the originals were his first Pokémon games. “It’s the game where I transitioned from being a fan of Pokémon to working on the games,” Ohmori says. He worked on the maps for the originals, but had more responsibility for Omega and Alpha.

“I was the director on it,” Ohmori says. “I kept hearing from Masuda about how hard the original Ruby and Sapphire games were and I kind of had that pressure in mind while creating Alpha Sapphire and Omega Ruby. But from my perspective, it was a lot of fun to work on the original Ruby and Sapphire, so I was super motivated to work as the director on the remakes.”

The games marked a first for the Pokémon series with the integration of soaring. For the first time (and last, to date), players could climb on the back of a Latios or Latias to fly over the land of Hoenn. Players could always use flying Pokémon to fast-travel, but this marked the first time players could actively control the flight.

Historically, remakes following new titles marked somewhat lower sales for Pokémon games, but Omega Ruby and Alpha Sapphire spurned that trend – to date they have sold more than 13 million copies.

Game Freak leaned harder into the 3DS hardware for Pokémon’s best-looking entries. Despite not marking a platform change for the series, Sun and Moon were still a difficult project for Ohmori, the game’s director. “I didn’t go to the hospital, but I definitely had a lot of stomachaches on Sun and Moon just from the stress,” Ohmori says. “One of the main reasons, or one of the most challenging for that, was with Sun and Moon we knew we kind of wanted to shake up the typical gameplay and structure of the games a little bit.”

“We knew we wanted to use this four island concept and take the player across the different islands and each island would have its own kind of type that is strong,” Ohmori says. “That concept of how they would experience the game really came first.”

The game launched during Pokémon’s 20th anniversary and marked Masuda’s exit from director duties for the original core Pokémon releases, which was why Ohmori did his best to try and change up some of the series’ core concepts. Players still train and fight Pokémon, but a new trials system made players perform strange tasks, such as photograph ghost Pokémon, or participate in atypical battles to acquire badges. “That feature actually really wasn’t locked down or figured out until we really went into the main debugging phase,” Ohmori says. “I was really paying attention to social media when the games came out just to see if people would accept this new trial system, and the impression I got was that they did seem to like it in general and it made it feel fresh.”

It was so late, in fact, that the programming and art teams were not able to lend much help for the trials’ creation. “I had to figure out a way that just us game designers could create these features and figure out the content of the actual trials. So we had a basic scripting language we could use, but obviously we couldn’t create new visuals,” Ohmori says. “We were trying things like maybe we have a sound quiz or something, so we came up with a lot of ideas based in the restrictions we had.”

The Future Of Pokémon

We know only a few things for certain about the future of Pokémon. Game Freak is revisited Sun and Moon for follow-ups called Ultra Sun and Ultra Moon that released in November on 3DS. This new version included an alternate story, along with Pokémon that weren’t previously included, among other changes.

Which brings us to Nintendo Switch. At E3 2017, The Pokémon Company’s president and CEO, Tsunekazu Ishihara, appeared briefly in Nintendo’s Spotlight presentation to confirm that a core Pokémon RPG is currently in development for the platform, and while visiting Game Freak, the developer was expectedly cagey about the game.

When talking about the necessity of Pokémon being on a handheld system in order to promote face to face interaction, we brought up the fact that Switch is the first home console that will allow you do this, and Masuda agreed – but that was all he offered.

One thing both Masuda and Ohmori are happy to talk about, however, is the excitement for Nintendo’s new console and bringing a Pokémon game to it. “What I’m really curious about, and really excited to see, will be the main way that people play the Switch,” Masuda says, “Will it be home for the most part? Will it be out and about? I think that is really going to depend on where the person lives, maybe. Depending on the country, maybe the main style of playing will be different. As we’ve been saying a lot, we always focus on, when designing the games, thinking about how the player is going to play the game – how they’re going to enjoy it, and what kind of experiences they are going to have. I’m really just kind of excited to see where the main style of playing is going to land.”

Masuda also acknowledges that for the Switch game, it’s not a typical platform transition. “It’s definitely different this time,” he says, since players will be able to choose to play like they always have, in handheld mode, or on a big screen in their living rooms, like they would a typical console RPG. “Just playing it at home is kind of a little bit different than the portable systems we’ve made games for up until now.”

Game Freak is watching feedback carefully, paying especially close attention during E3. “It definitely is really fun to see that, but at the same time, it is definitely a lot of pressure, so we’re going to do our best to create a great game that answers those expectations,” Ohmori says.

With more than 20 years under its belt, the Pokémon franchise has become a surprising juggernaut that only seems to grow, even when it faces accusations of being an expiring fad. Its latest release, Sun and Moon, recently passed the 15 million copies sold mark, sits high on the list of Nintendo’s fastest-selling games, and is bested only by Pokémon X and Y for the 3DS’ best-selling games. Even Pokémon Go, which lost a healthy percentage of its initial player base after launch, still boasts over 60 million active players.

How a yellow electric mouse with a limited vocabulary and its 801 friends can continually enchant the world is impossible to identify, and visiting the studio didn’t reveal any of its secrets to success. Game Freak is a humble team that quietly crafts its Pokémon experiences in an office that feels more like a home. It is fully aware of its impact on the world, but understands that Pokémon has become something bigger than themselves. Even as it ramps up and expands to develop its first true console Pokémon experience, Masuda is careful to temper expectations. “Of course, it is very difficult to make the game, so I hope people don’t get their expectations up too high,” Masuda says. “We’ll do our best."

For even more from our trip to Game Freak in Japan, follow the links below for more features from our History of Pokémon coverage.

This feature originally appeared in the September 2017 issue of Game Informer.

Explore your favorite games in premium print format, delivered to your door.