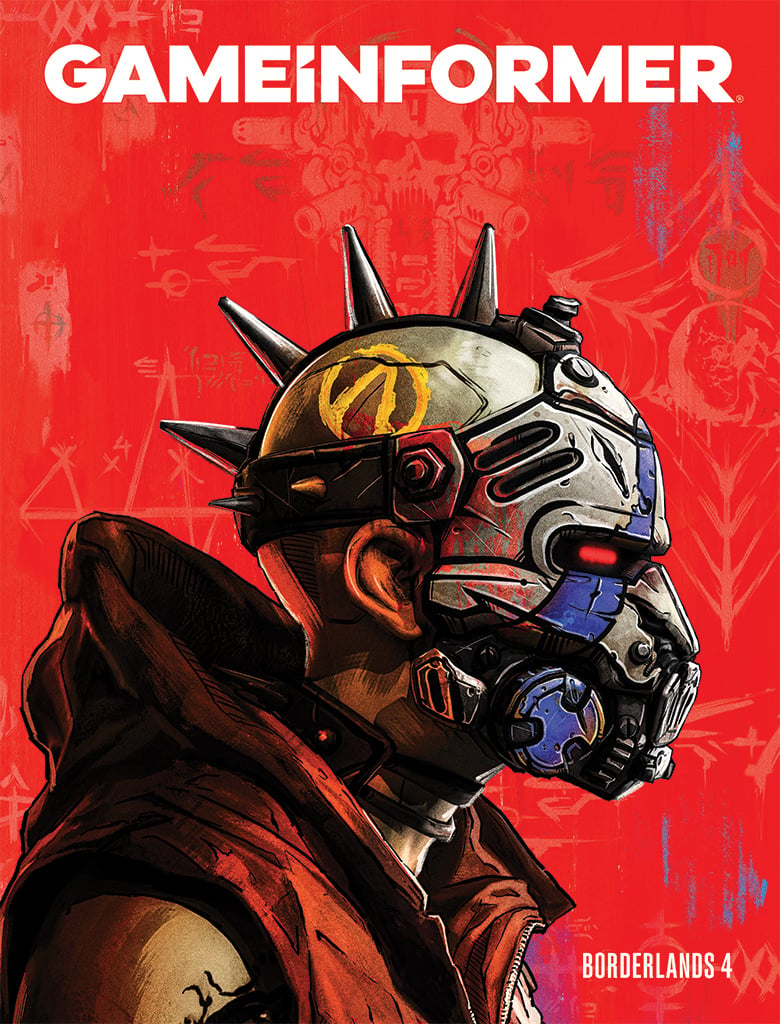

Borderlands 4 debut issue is already available for Digital subscriptions. Subscribe Now!

How Rare Cast Away Its Developmental Process For Sea Of Thieves

Rare was once a giant in the industry. The enigmatic U.K. studio built a legacy on innovative and often off beat classics like Donkey Kong Country, Banjo-Kazooie, and Perfect Dark. In the ’90s, Rare’s name was virtually synonymous with quality. But over time, that reputation faded. A series of lackluster releases like Grabbed by the Ghoulies, Perfect Dark Zero, and Kameo: Elements of Power took the shine off Rare’s star. Today, the studio is best known for its work on the Kinect Sports series and constructing the Avatar characters that once represented Xbox Live users and have now become largely ignored.

Rare hopes to change this image with the release of Sea of Thieves – a shared-world action game where players team up to crew a pirate ship and role-play the life of a treasure hunter. In order to develop a game it hopes lives up to its past genius, the studio has invited a community of fans into the creative process.

[Editor's Note: This feature originally appeared in issue 296 of Game Informer Magazine]

Setting A New Course

For most of Rare’s 30-year history, the studio has been notoriously secretive. Tucked into the middle of the British countryside and surrounded by sheep farms, Rare’s offices are so nondescript that cab drivers struggle to find the building. The company’s 90-plus acres of rolling hills and trees seem like an idyllic place to make games, but those trees have also shielded Rare from eager fans looking to get a peek at the studio’s next project.

For a long time, Rare’s efforts were a mystery even to its own staff. The studio’s offices are broken into four interconnected buildings, called barns, and developers who work in one barn haven’t traditionally been allowed inside any of the company’s other barns. This meant that the team that worked on GoldenEye 007 had no idea what the Banjo-Kazooie team was working on, and vice versa.

This air of mystery worked for several decades, but seemed almost paranoid in the modern era of social networking and global sharing. When Craig Duncan took over as studio head in 2010, one of his first priorities was tearing down those walls.

Over the years, Duncan has been trying to build his own legacy within the U.K. game industry. As the head of worldwide development for Codemasters, he helped develop games like Grid, Rise of the Argonauts, and Worms 4: Mayhem before heading up U.K. studios for both Sega and Midway.

“When I first started talking to Microsoft about a leadership role in the U.K., Rare quickly came up,” Duncan says. “I grew up playing Rare games, and I had a view of what I thought Rare was, but I didn’t know anyone that worked at Rare, which was strange because I knew everyone who worked in U.K. development…When I came in I was like, ‘Okay, what have we got? What’s Rare now? And what do we want Rare to be in the future?’”

Duncan remodeled Rare’s offices, creating a more open layout that encouraged idea sharing. This new design was symbolic of Rare’s new approach to game development under Duncan. The studio wanted to be more open with its fans and show the industry that it still had the steel to create a new IP that lived up to its legacy. As the rest of the studio developed Rare Replay, which was a celebration of Rare’s past, Duncan put together a skunkworks team and tasked them with figuring out Rare’s future.

“We looked at industry trends, at what was popular and tried to guess about where the industry was going,” says executive producer Joe Neate. “We really liked shared world games like DayZ, Eve Online, and even Journey. Games that had a DNA that allowed for interesting, player-created stories. The scale of some of those stories was huge, with betrayals that took place over the course of 18 months. We wanted to make a game like that, where stories came out of the very fabric of players playing together.”

The team began to dream about the kind of shared world Rare could build. They wanted to make a game that had a lower barrier to entry, one that would appeal to a wide audience but would also continue to foster a welcoming community as it grew. For a time, the team played with game ideas as far ranging as deep-space adventures, masquerading vampires, and lost dinosaur islands. Nothing felt right.

And then someone suggested pirates.

Sailing The Three Seas

In five months, a team of only five engineers and a couple designers built a prototype for their pirate game, which they dubbed Athena. The game looked crude, but it featured all the major concepts that are still part of the game. Players join a party of around four and work together to pilot a ship to uncharted islands where they hunt for buried treasure and fight off other treasure hunters before bringing their spoils back to port.

Three years later, the game looks much better, but it feels surprisingly similar to that original concept. The ocean, however, has grown a great deal. Players can now traverse three distinct biomes. The first of these zones, called The Wilds, is an oppressive seascape of dark clouds and islands that feel like they’re barely clinging to life. Players sail past ship graveyards where the dreams of pirates have crashed against the black sandstone. Beautiful blue skies and white sand await players that make their way to The Shores of Plenty, which is an idyllic pirate paradise. Those who crave a different kind of adventure can chart a course for the Ancient Islands, an Indiana Jones-inspired nirvana filled with temples, totem poles, and scattered signs of ancient civilization.

As players travel through these exotic locales, they complete quests and solve riddles to find buried treasures, battle skeleton warriors, and dive into the ocean to loot ancient shipwrecks. These adventures are all the more unpredictable thanks to the fact that every other ship on the water is crewed by other players. You’ll never know who’s out to steal your loot and who’s eager to run from a fight.

Rare says it isn’t worried about crafting a larger narrative that ties these quests together, but the individual quests will eventually come packaged with their own tiny narratives. All this treasure hunting begs the question: What will players do with all this bounty? Unfortunately, Rare isn’t ready to go into detail about its progression system until closer to launch.

“There are a lot of games out there that rely on the feeling of, ‘How much did I increase my stats?’” says design director Mike Chapman. “’How many of my twos turned into threes and how many threes turn into fours?’ In that world, if two people come across each other and one person sees that the other is 20 levels above them, they’re always going to run away, because they have no chance. We want you to feel like you’ve always got a chance, so our progression system is not a single number. I don’t see you and say, ‘Oh, you’re a six and I’m a five. You’re better than me.’ Instead, you’ve got unique cosmetics that are like trophies.”

It’s easy to imagine that players will be able to buy entire wardrobes of distinctive cosmetics and even replace limbs with Piratey prosthetics. Rare has already added several new weapons – such as a shrapnel-spewing blunderbuss – to Sea of Thieves’ alpha. However, Rare also plans to give experienced players access to more exotic quest chains, which feature ever-greater rewards. Still, these rewards won’t be limiting to other players, since newer crewmates can join in on these epic quests and reap the same rewards.

Players can also explore Sea of Thieves’ world by themselves on a smaller ship if they want to, but one of the most interesting aspects of Rare’s experience is how it has created an environment that encourages players to work together. Sea of Thieves features no classes or other specialization. Instead, Rare hopes players naturally fall into the roles they’re best suited for. Crewing a massive galleon takes many hands, and a captain won’t always be able to see where he’s going from the navigation wheel, so he needs people in the crow’s nest offering directions while other players turn the sails into the wind. In the chaos of combat, players might need to bounce between multiple roles. While one player mans the cannons, another might have to run below deck to repair leaks.

For the sake of fun, Rare isn’t aiming for historical accuracy. Players can use pistols underwater to subdue bloodthirsty sharks, fire themselves out of cannons to reach shore, or enlist the help of mermaids to repair a broken ship. Rare often incorporates humor into its games, but Sea of Thieves’ brand of whimsy is more interactive. Rather than doing stand-up, Rare is hosting improv comedy. This subtle shift shows Rare’s desire to interact with its community. When the studio first began work on Sea of Thieves it had no idea how drastically that little shift would influence the game’s development.

[Up Next: How Rare used its community to improve the world of Sea of Thieves.]

A Pirate’s Life

Charting the course for Sea of Thieves, the studio figured it would be able to predict player retention based on how much players talked to each other while playing. The team guessed that those who talked with each other a lot would most likely have a good time and play the longest, those who didn’t talk would probably play the least, and groups with a mix of both kinds of players would fall somewhere in the middle. When Rare invited players into its closed alpha in December of 2016, it tracked this kind of data and quickly learned that its predictions were wrong.

Groups that talked a lot did tend to return to the game regularly, but groups that didn’t talk amongst themselves would also play for extended periods of time. In fact, they often discovered creative ways to communicate with one another, like shooting their guns at objects they wanted each other to notice. Players in mixed groups of talkers and non-talkers actually had the least fun. Rare now understands that players enjoy the game most when they spend time with like-minded players. This insight was crucial for the team, because it helped the studio understand how to better bring people together.

“Our game is a friendship creation tool,” Neate says. “We want to turn as many strangers into friends as we can. A lot of the stuff on our roadmap allows players to make new friends, because that will lead to a healthier community. We intentionally have the social lubricants like the drinking and the music, because when you play music and you dance around or you have a drink and stumble all over the place, you kind of laugh and smile. When you do that with strangers, you’re much more likely to make friends, just like you would in a real pub.”

The data Rare collects from its alpha tests sharpens the game in other ways as well. For example, in Sea of Thieves’ earliest conception, when players found a treasure chest, they got to open that chest immediately and one member in the group had to hold the treasure. Rare discovered that 90 percent of the time, crews devolved into mutiny as the players wrestled over who got to hold the treasure. This ran counter to Rare’s desire to create a spirt of cooperation and foster friendships, so it changed the process, requiring crews to physically haul the treasure chests back to port before the spoils were evenly distributed amongst the whole crew.

As Rare continued thinking about how to encourage players to work together while transporting chests, the team came up with a series of unique chest types. The ultra-rare chests contain a lot of gold, but they also break the rules of the game in fun ways. For example, a chest called the Chest of a Thousand Grogs looks like a grog keg. When players pick up this keg they instantly become drunk, so their fellow crewmates must watch over them as they cart the chest back to the ship. Another chest, called the Chest of Sorrow, features the carved likeness of a face in agony. This chest constantly cries and will slowly fill the players’ ship with water, forcing them to work together and continuously bail out their cargo hold as they make their way back to port.

“We found that it sort of bonds a crew together, because they just want to get the chest back and get the gold inside, but it uses the mechanics of bailing in a different way,” Chapman says. “However, in the very third session after we put that chest into the game, people were already using it as a weapon. They would sneak onto other players’ ships and hide the chest somewhere. Then the opposing team would suddenly be like, ‘Why are we sinking? Where is all this water coming from?’”

X Marks The Spot

As a way of saying thank you to its fans, Rare is constantly looking for ways to incorporate Sea of Thieves’ players into the game lore. One of the first ways the studio did this centers on death. When players die in-game they are transported to the Ferry of the Damned, where they wait to respawn back into the world. Players from all across the in-game world get transported onto the same ferry when they die, and Rare says that some players from opposing crews have become friends after meeting on the Ferry of the Damned. The first player who died in Sea of Thieves and journeyed to the Ferry of the Damned (which happened only four minutes after the servers were turned on) got his name carved into one corner of the ferry.

Other notorious players have had their likenesses carved onto wanted posters and had in-game pubs named after them to memorialize their deeds. At one point, Rare noticed that a player had fallen to his death several times more than any other player, so the studio made a memorial to him at the bottom of a nearby cliff. Rare eventually learned that this player was intentionally jumping to his death so that he could respawn with refilled health.

These little tributes do more than color the world; Rare considers these stories a part of the world’s lore and references these unique locations in quest riddles, incorporating them into the treasure hunts that are the core loop of the game. This is something the studio expects to continue even after the game has launched.

“I don’t think you can make a shared-world game about player motivation without bringing players on the journey with you,” Duncan says. “I don’t think you get enough feedback. [Microsoft’s executive vice president of gaming] Phil Spencer actually jokes that, ‘You tell your fans more about this game than you tell us.’”

Rare cares more about how its fans feel about Sea of Thieves than what its corporate stakeholders think. For Rare, Sea of Thieves has been a journey to create a game that lives up to the studio’s storied legacy. But it’s also about something else: creating a game different than anything it has done before. It remains to be seen if Sea of Thieves’ progression system has long-term hooks, but Rare has accomplished its goal of making something unique.

Sea of Thieves allows players to create their own adventures. It’s a world where everyone is welcome, and where every member of the team is important and the team doesn’t compete against itself. In that sense, it’s fitting that Sea of Thieves is about pirates.

“Largely this is how pirates actually lived,” Chapman says. “They voted on the effects of the crew. They decided which ships they were going to sack. They operated like a democracy. There were female pirates and pirates of every kind of creed and race from around the world. They were very forward-thinking because everyone was welcome. Everyone was equal.”

That’s the real spirit of piracy that Sea of Thieves aspires to emulate.