How A Fighting Game Documentary Survived 9/11 And Became A Cult Favorite

This article was originally published in issue 289 of Game Informer.

On the day Peter Kang’s years-long passion project went up in flames, it wasn’t his biggest concern. Two commercial airliners had just collided with the World Trade Center in New York, and while the morning news was inundated with coverage of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, Kang didn’t need to watch. “I looked out the window, and of course the north tower’s on fire from the first crash,” Kang says. As he was escorted out of Battery Park to safety by the NYPD, the Street Fighter documentary he’d been editing was the last thing on his mind.

But since then, Kang’s been thinking about it a lot. After turning what little footage he had left into the award-winning film Bang the Machine, he’s been on a 15-year, on-and-off journey to have it see the light of day. The road has been rough and Kang still hasn’t defeated the film’s toughest opponent, but as in the scene he documented at the turn of the millennium, victory is always within reach.

From Designer To

Filmmaker

Bang the Machine, a documentary series chronicling the

emerging arcade and online culture of Street Fighter competitions, was the

brainchild of Kang and Gene Na. The two were partners at Kioken, a cutting-edge

web design agency with high-profile clients such as Diddy and Jennifer Lopez. A

few years in, they decided to sell the company in order to pursue a life-long

passion. “I was a big Street Fighter fan, I used to play on all the arcades,”

Kang says. In fact, the two had met playing Street Fighter II in arcades, so

naturally, they wanted to honor the community they’d been a part of for years.

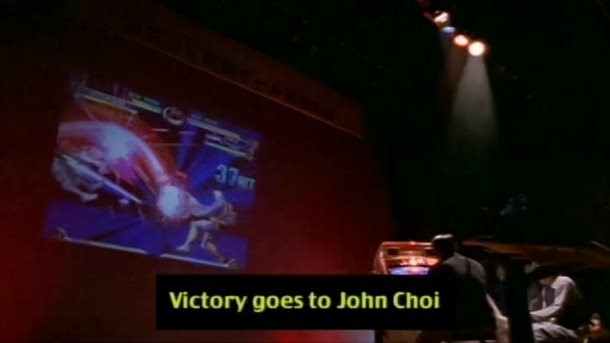

Around that time, Kang was in San Francisco for a client meeting and decided to visit Southern Hills Golfland, a popular destination for the West Coast’s best Street Fighter players. There he met players like John Choi, Joey “Mr. Wizard” Cuellar, and Alex Valle – people he’d heard about in magazines and online IRC channels, but never met in person. They became fast friends, and after returning to New York, Kang and Na got to work. “We decided that since we had access to these people, if we could find a director we could start a film-production company with the hopes of licensing this [project],” Kang says.

That director was Tamara Lowe, a film student at the Rhode Island School of Design. Lowe was introduced to the pair through her roommate, a senior designer at Kioken. Lowe had been interested in making a documentary for a while, but wasn’t aware of the scene. “It was a steep learning curve for me, because I wasn’t a gamer,” Lowe says.

To orient Lowe in arcade culture, Kang took her to Chinatown Fair, a New York City arcade. There Lowe spent hours talking to players, learning their stories and nitty gritty details, such as how the survival-of-the-fittest and region-oriented culture of arcades sparked competition, and how players dreamed of playing video games for a living someday.

Select Your Character

Next, the film’s crew needed players to follow. Among the

most popular games at the time was Street Fighter Alpha 3, and Alex Valle was

its American champion. Valle wasn’t on board with the documentary at first, but

changed his mind after speaking with Tom and Tony Can non, twin brothers who

ran the tournament the film would center around, B4 (Battle By The Bay, which

would later become The Evolution Championship Series, best known as Evo).

The film highlighted several players, including Valle, over the course of a year as they compete throughout Northern and Southern California in the lead up to B4. The stakes for B4 were higher than most other tournaments, since victory came with the chance to travel to Japan to compete in a fighting-game exhibition pitting the United States against Japan in a number of fighting games. “Back then traveling internationally was unheard of, because it was so expensive” says Cuellar, who helped run B4. “People almost never traveled for video games back then.”

Bang the Machine captures much of the raw passion that permeated the Street Fighter scene at the time. Though playing for your local region is still a big part of competitive gaming, rivalries were both more local and more heated in the late ‘90s and early 2000s. “There was no just being friendly and kind to everyone, it was super fierce,” Cuellar says. “If one of your rivals beat one of your team members, it was pretty personal.”

An Upset Victory

After filming for the better part of a year, the team got to

work putting the series together (see sidebar). Unfortunately, the team’s

office was located directly south of the south tower of The World Trade Center,

and on Sept. 11, 2001, most of the digital footage, some film footage, and much

of the audio for the film was destroyed. “It was terrible,” Lowe says. “People

lost their lives. And in comparison to that kind of loss, a documentary about

gaming didn’t seem like something that I could get that upset about. But I was

pretty devastated.”

Not all of the footage was lost (some of the film negatives at a processing lab survived), but the team had to severely reduce the scope of the project. Scenes were cut and characters were removed. Most of the audio came from VHS tapes Kang and Lowe had been bringing home from the editing studio. “What survived, that kind of dictated what kind of story we were going to tell,” Kang says.

Lowe, Kang, and the crew put together an early cut that made it into the 2002 SXSW film festival, where it screened for hundreds of people who knew nothing about the fighting- game community. Viewers flocked to the film. “We had a certain number of screenings, and we had to schedule more because it was such a big turnout,” Lowe says. Bang The Machine ended up winning an audience award at SXSW, and anticipation for a full release was high.

A Daunting Challenge

Unfortunately, that didn’t happen. Despite the reception, no

distributor picked the film up for a full release. The documentary also used a

number of licensed songs from prominent artists, which made it expensive to

release. And because much of the footage used in the film came from screener

tapes that had already been finished, the audio and video were already meshed

together. “We had like a Beatles track or a Chemical Brothers track mixed in to

Valle speaking, and we couldn’t separate the two,” Lowe says. Because the

company couldn’t pay the fees to license these songs, Bang the Machine couldn’t

officially release.

Despite the setback, the film slowly developed a cult status within the fighting game community. In 2004, Cuellar reached out to Kang about getting a copy of the film (of which there are only a handful) for a small screening at that year’s Evo tournament, after which Kang overnighted a DVD of the film. Since then, Cuellar has occasionally shown the film to small crowds at Evo tournaments. Beyond that, however, few outside of the crew’s friends and families have ever seen it.

Fight For The Future

Though the crew behind Bang the Machine has moved on, Kang

still keeps up with Lowe, as well as players like Valle, Cuellar, and John

Choi. “We’re all still super-tight. Everyone still talks to each other every

day,” he says.

Kang hasn’t given up on the film, either. “The plan has always been, and we haven’t changed our minds, but we will get this thing released at some point, come hell or high water,” he says. The biggest issue is still the music licensing rights, which Kang hopes overcome by running a fundraising campaign to pay the fees, which Kang estimates would total around $300,000. The core team also has plans for a sequel of sorts, catching up with many of the players featured in the original film.

If the film does receive a full release someday, it’ll be in a context far removed from the one that birthed it. Originally conceived as a way to show a larger audience the future of competitive gaming, Bang the Machine now acts as a time machine to its nascent past. But for all that has changed in the years since the film’s release, Kang still sees it as the distillation of the fighting game community’s inclusive spirit. “It didn’t matter who you were,” Kang says. “Everyone’s just kind of blind to the normal tags people have on themselves, how the world usually segments us and kind of divides people.” Considering the circumstances which nearly destroyed the film, it’s a powerful message.