Opinion – Unfriendly Controls Can Make Horror Games Better

It’s a familiar experience: you start up a new game, and something feels weird. Actions aren’t happening at the right time or the right speed. Something’s off with the way your character turns. The controls just feel bad.

"Bad controls" usually mean we’re not getting feedback that matches what we’re seeing or doing. Games have developed an established control language over the years, which most gamers have already internalized. Spacebar means jump, the right trigger means shoot. When a game doesn’t follow these unwritten rules, it’s jarring and difficult to readapt.

Dark Souls felt bizarre and unfriendly in my hands when I first picked it up, and my initial steps through that game were all the more frightening because of how alien the control scheme was. I inched my way forward, in part because I quickly learned that Dark Souls enjoys hiding enemies behind blind corners, but mostly because I wasn’t sure I’d react properly when I got attacked.

The game had made me anxious and unsure of myself, just by mapping my controller inputs in an unfamiliar way. That was, I think, done on purpose. Sometimes feelings of uncertainty and tension are exactly what a game needs.

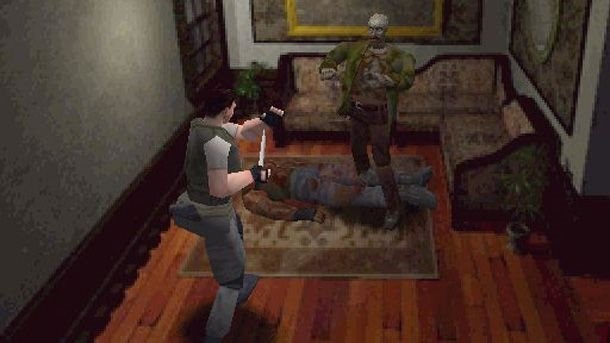

Take the first Resident Evil game. Originally released in 1996, it featured polygonal characters exploring a blighted mansion with pre-rendered 2D backgrounds. As you moved from scene to scene, the camera angles changed dramatically. This led the developers to use so-called tank controls, which keep you moving forward as long as you press up on the stick, but require you to rotate, rather than strafe, using left and right. Tension is built into this control scheme – if something is chasing you, you have to stop and then watch as your character slowly turns around to face the threat. It evokes that nightmare of running away from something, but finding that your legs don’t work properly.

Resident Evil almost single-handedly created the survival horror genre (the term was coined by Capcom for the game’s marketing), and the army of clones it inspired frequently used the tank control scheme. This made sense while everyone was still using the limited processing power available during the original PlayStation era, but survival horror games continued to use tank controls even when new hardware allowed games to use fully-rendered 3D scenery with cameras that followed the player. Capcom even opted to use an adapted version of these original tank controls for Resident Evil 4, one of the Game Informer's top 25 horror games of all time, even though players had begun to expect the ability to strafe, shoot, and turn on demand.

Why? Because horror is scarier when you have to struggle, and the clunky control scheme means you’ve got to physically struggle (albeit, with your fingertips) to accomplish time-sensitive tasks in-game.

Technical limitations in 1996 led to the development of a control scheme for Resident Evil that enhanced the tension and (arguably) the overall horror experience. Compare this to Ridley Scott’s masterful 1979 film Alien. Because of budget constraints, Scott’s team was unable to make a fully-articulated, working Xenomorph that looked convincing on camera. But by surrounding small, manageable parts of the alien with darkness, they forced viewers’ imaginations to fill in the blanks. What we came up with in our minds was far scarier than anything they could have put on the screen.

By the time Alien: Isolation came out in 2014, the Xenomorph was a well-established pop culture icon. There’s nothing to hide on the creature now that we’ve repeatedly seen the whole thing thanks to modern CG. Creative Assembly had to find other ways to evoke the dread and terror of the original film, and one way they accomplished this was by making some of the player’s important interactions with the game inherently frustrating. Player-character Amanda Ripley must physically reach out and manipulate each button or lever to interact with them, and in the retro-future setting of Sevastopol station this takes in-game time. Even saving your game is done by painstakingly interacting with the environment. That’s time during which you can be horribly killed by the alien that’s stalking you, and it’s excruciating. You’ve been trained to expect instant feedback when interacting with game environments, and Alien: Isolation preys on that expectation. It creates a tension reminiscent of the final moments in Alien, where Ellen Ripley races to disarm her ship’s self-destruct sequence. This is different from what’s usually considered “bad controls;” Alien: Isolation’s controls work fine. But a save system that deliberately creates this kind of player discomfort has a lot in common with Resident Evil 4’s awkward shooting controls. Both games want you to empathize with the character you’re playing on a physiological level.

It certainly worked on me. After one late-night, multi-hour session of Alien: Isolation, I hit a save point and decided to call it a night. As I exited the game and went to stand up from my desk, I became aware of how tense the muscles in my legs were. The color was starting to return to the whitened knuckles of my right hand, which had been clenched around the mouse.

Dying Light is another game that uses its control scheme and feedback in order to create added tension. As Brian Shea wrote in his review, combat at the game’s outset is usually not worth the effort, especially if there are more than a couple zombies around. Clumsy and awkward in the early hours, Dying Light’s combat system evokes the kind of stress and haplessness that characters in Dawn of the Dead or The Walking Dead might actually experience. Getting into scraps in the streets as you start out is usually a terrible idea, as it’s exhausting and likely to attract the attention of the more dangerous "virals." As in classic zombie fiction, you generally want to avoid fighting zombies.

This pushes the player toward the game's parkour system, which has its own weird control scheme. To jump and grab ledges, you press the right bumper. This allows you to always keep your thumbs on the control sticks, but it can be a disorienting button mapping when you start playing the game. My hands felt weird holding the controller like this, almost the way they did with Dark Souls, and that never completely went away. That physical weirdness makes sense in the context of what’s happening in the game. As Kyle Crane, you’re dropped into the foreign country of Harran to help survivors of the zombie outbreak. Unlike Faith in Mirror’s Edge, Crane doesn’t start as a parkour master. You’re learning parkour from the characters you meet and from practice. He’s new to the city and new to parkour, so he can’t see the right paths to take the way Faith can through her vibrant "runner vision." Making a big jump in Dying Light always feels at least a bit risky to me, and in the back of my head I can’t help but wonder "Can I make this?" Here again, "bad" controls are helping communicate something important to the player; in this case, it’s the inherent danger of real parkour.

While each of these games – Resident Evil, Alien: Isolation, and Dying Light – has a tense theme and controls that reinforce it, it’s far from settled whether these control schemes were deliberately designed to accomplish that, or whether it’s the best possible approach in a particular game’s design. Critics and players alike have (justifiably) complained about the control schemes in these titles, and even though I’ve had my own frustrations with them, I think that might have been the point all along. It’s true that countless games have crummy control schemes that make them less fun to play without adding anything meaningful. But it’s also possible to design tension into control schemes well. Grand Theft Auto V’s driving proves that point – imagine how absurd and meaningless the garbage truck mission would feel if the vehicle handled as well as a sports car. Another great non-horror example of this is Papers, Please, which has you shuffling papers around a cramped workspace in order to reinforce the sensation of working under an autocratic bureaucracy.

Building discomfort into entertainment isn’t a new idea. Making audiences feel uncomfortable is something art has been doing for a long time. Ghost stories and horror movies poke at our fears of the unknown and our fight-or-flight instincts just enough to push us out of our comfort zones, and at least for fans of the genre, that’s what keeps us coming back. What games bring to the table is interactivity, and the point of interaction is usually the controller, the joystick, or the keyboard and mouse. Smart designers have recognized that these can be used alongside games’ audio and video, and their stories and characters, to enhance themes of fright and tension by allowing the players themselves share in those experiences.

Get the Game Informer Print Edition!

Explore your favorite games in premium print format, delivered to your door.

- 10 issues per year

- Only $4.80 per issue

- Full digital magazine archive access

- Since 1991