The Fearsome Folklore Behind The Witcher III: Blood And Wine’s Monsters

The Witcher series is steeped in mythology, both of its own creation and drawn from reality. However, nothing is more folkloric than the monsters Geralt faces – which draw inspiration from Slavic, Germanic, Scandinavian, English, and other lore. The Witcher III’s new DLC takes players to Toussaint, the land of Blood and Wine. Although its lush hills and contented people make Toussaint appear untouched by shadow, this DLC also brings almost 30 new monsters to fight. Geralt’s bestiary may differ from the true mythology of these beasts, but the traces of their fictional sources may be present in their entries. Ever wonder where CD Projekt Red may have drawn inspiration for the temptress vampire the bruxa, or her more dangerous cousin the alp? Get acquainted with the possible real-life inspiration for the lore of some of the most interesting new monsters in the land of vampires and vineyards.

[Warning: this feature has Witcher III: Blood and Wine spoilers from various points in the game.]

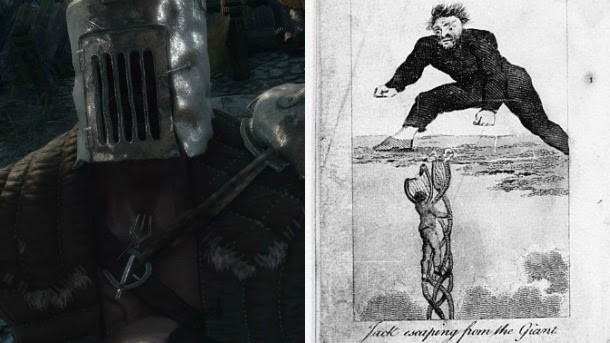

Cloud Giant

In Folklore: According to Durham University anthropologist Dr. Jamie Tehrani, the story of Jack and the Beanstalk originated within a group of stories entitled The Boy Who Stole Ogre’s Treasure, dating back over 5,000 years ago. The modern iteration of the fairy tale known firstly as The Story of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean is an English fable that's first printing dates back to the early 18th century. The popularized tale of Jack and the Beanstalk follows Jack as he attempts to procure a golden goose from a giant residing in the castle at the top of a beanstalk.

In The Witcher: In Blood and Wine Geralt helps Jack, and climbs a beanstalk to fight against the monstrous Cloud Giant. He was originally a peasant strongman who became “degenerated and overgrown” until he turned into a monster. His armor is made from various pieces of furniture including what looks like an oak stove oven for a helmet, while his gigantic weapon is part hoe, part pitchfork. He ducks in and out of the clouds to attack Geralt from various different angles. The bestiary makes direct reference to his part in the English fable stating, “After Jack stole his goose that laid golden eggs, the Cloud Giant decided anyone who climbed onto his cloud would be tossed off, without a word of warning.”

Bruxae

In Folklore: Originating in Portugal, the bruxa is a woman-turned-vampire through witchcraft. Prominent in the Middle-Ages when The Inquisition targeted pagan and satanic beliefs, Portuguese lore states a bruxa sucks the blood of infants and assumes the shape of various animals including a duck, ant, rat, goose, or dove. Steel and iron was said to deter them, with children tucking a pair of scissors under their pillow at night or even sewing garlic into their clothing in the hopes it would keep them at bay. If children were to die and a bruxa was suspected, the parents would boil the clothes of the deceased child while stabbing them, believing the bruxa would also feel the jabs.

In The Witcher: The bruxa was included in the first two Witcher games, but was scratched from the third during development. Now they are returning in Blood and Wine, and are one of the first monsters Geralt encounters when arriving in Toussaint. In the Witcher series, bruxae use the power of invisibility and their screams offer a devastating sonic blow. They are rare creatures that live away from population centers, but can assume the shape of an attractive woman around humans while their natural form is much more grotesque. They have sharp claws and, like any vampire, suck the blood of their victims.

Alps

In Folklore: From Germanic folklore comes the alp, a typically male creature that ignites nightmares in its victims. It sits upon the chest of a sleeper and becomes heavier and heavier until they awake, breathless and immobile. Their attacks are called alpdrücke, translating to ‘elf-pressure’ or nightmare, and strongly aided the origin of the word. These demons were likely an attempt at explaining disorders such as sleep apnea or insomnia. It can shapeshift into a pig, cat, dog, snake, or white butterfly, but no matter its form it always wears a hat called a tarnkappe that grants it the power of invisibility. These guys were pretty mischievous, souring milk, re-diapering babies, and even trying to suck the blood from the nipples of men and children, and the milk from women. Probably the most interesting method of deterring an alp was to urinate into a clean bottle, let it sit in the sun for three days, walk down to a stream without saying a word, and toss it into the water. Boom, nightmares cured.

In The Witcher: Alps appeared in the first Witcher, and are back once again in Blood and Wine. Their gender is strictly female, contradictory to the Germanic lore, and are akin to the bruxa in appearance with bloody naked bodies and long claws.They dart around with amazing speed, using the same sonic screams as bruxae. However, contrary to the Witcher III cinematic trailer, alps are not able to turn invisible like their so-called-cousin the bruxa. They can take on the form of a normal woman, which allows them to blend into crowds. In the Witcher universe alps also are associated with nightmares, as their saliva can cause one to fall asleep and when applied to an already sleeping man can bring on terrifying nightmares. They attack at night, most often when the moon is full, and are usually found near smaller villages.

Daphne’s Wraith

In Folklore: In Greek mythology Daphne was a naiad, a female nymph associated with bodies of fresh water. She was so beautiful that the Greek god Apollo pursued her relentlessly until she was so exhausted she called up to either her father, the rivergod Ladon or Gaia, for help. Daphne was then transformed into a laurel tree, and artistic representations of the transformation show her sprouting leaves as Apollo clings to what's left of her human form. The laurel tree was sacred and directly associated with the god Apollo, and winners of the Pythian Games were crowned with a wreath of its leaves. After Daphne was transformed, poets say the only trace of her left was her beauty.

In The Witcher: While in Toussaint, Geralt hears of a woman who has been turned into a tree. Her bark bleeds when ripped, and as the wind travels through her leaves, it produces the sound of muffled sobs. Unlike Daphne the nymph, Geralt suspects the reason for this transformation is due to a sorrowful curse that occurred when the love of her life, a knight errant named Gareth, had gone to the witch of Lynx Crag to ask her to lift a drought on their land. Gareth refused to bend a knee to the witch, planning to force her to lift the drought, and thus never returned. An in-game book entitled Tales and Fables states, “Daphne stood on the top of a hill and looked for him night and day. Finally, she turned into a tree, so that she may live to see the return of her knight.” Geralt can attempt to free Daphne from her curse by offering up proof of her previous love with a kerchief, but it proves too much for her and the trauma transforms her once again, this time into a wraith. Geralt sadly explains to the woodcutter Jacob, “More like tore than freed her from her prison. Shock was too much. Released all the rage and pain that was in her.” The witch of Lynx Crag can also free Daphne, but with arguably an even worse outcome as Jacob dies as a casualty.

More monsters await on page two, including a grim-spin on the tale of Rapunzel.

Longlocks

In Folklore: The tale of Rapunzel is Germanic in origin, and was included in the famous collection of fairy tales by the Brothers Grimm. It was an adaption of the 1790 story of the same name by Friedrich Schulz, but plot similarities connect it to a 10th century Persian tale of Rudāba who let down her hair to allow her lover to unite with her. The story has Rapunzel, named by her mother for the pregnancy craving of a rapunzel flower, held within a tower by a witch named Dame Gothel. She is impregnated by a prince who climbs her hair into the tower, but Dame Gothel cuts Rapunzel’s hair and tricks the prince into climbing it once again, only for him to fall into thorns and become blind. After wandering the forest, he stumbles upon Rapunzel who has given birth to their twins. Her tears of joy heal his blindness and they live happily ever after.

In The Witcher: In Blood and Wine, Longlocks wasn’t as patient as the fairy tale Rapunzel. While waiting for her own prince, she grew tired and hung herself with her own braid. Her troubled spirit then turned into a wraith, forever waiting for her suitor. Geralt climbs her tower, only for a fight to ensue where she summons skeletons to distract him while she flies away to heal.

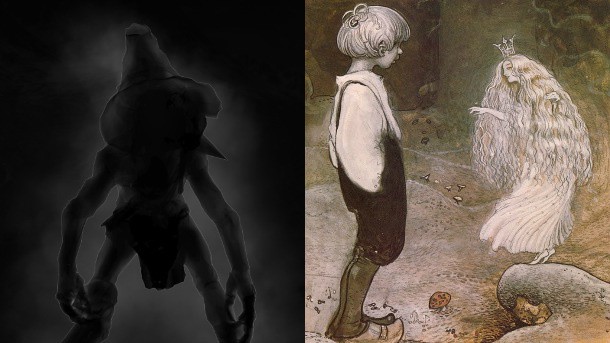

Pixies

In Folklore: Pixie lore comes from England, more specifically the south-west areas of Devon and Cornwall along the Celtic sea. They are famously mischievous, depicted as the tiny pranksters in the world of folklore. Pixies are essentially a sub-species of fairy, and it is suspected a great deal of the characteristics attributed to pixies are simply a cross-over from already-established fairy myths. They were taken seriously by populations in Devon and Cornwall before the 19th century, as legends state they would turn into rags to entice children to play with them. They are usually helpful to humans, but their mischievous nature has them occasionally pulling pranks or misleading a lost traveler or child. The cure to avoiding being misled by a pixie was to turn your coat inside out. They can shape shift as well, with their most common appearance being that of a hedgehog, but their natural shape was commonly naked. They are also lovers of horses, as stories say they would ride the Dartmoor ponies of south-western England, tying their manes into a pair of stirrups to gallop about the moors.

In The Witcher: Pixies in the Witcher universe were created to protect the Land of a Thousand Fables from intruders, as well as protect the future duchess of Toussaint, Anna Henrietta, and her sister, Sylvia Anna. They are much more combative than the Celtic pixies of lore, described as “aggressive, war-like creatures, created to kill, defend, and fight till they can fight no more.” Their appearance is shadowy and they attack in packs. Standing at about half the size of Geralt, they apparat out of thin air and move quickly, using their shadowy appearance to create a black fog around their victim as they dart about.

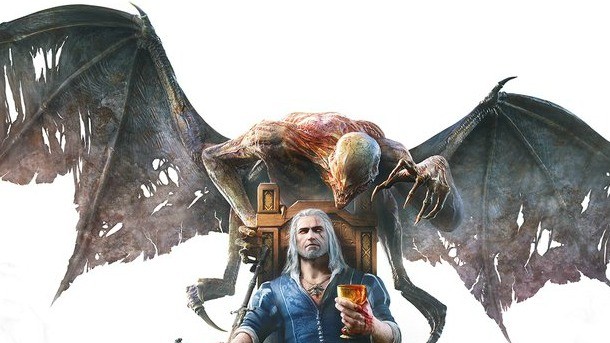

Dettlaff van der Eretein

In Folklore: This one comes with speculation, but higher vampire Dettlaff van der Eretein bares similarities to the lore of the German shapeshifter, the Aufhocker. It is never described as having a specific shape, but the Aufhocker is closely associated with vampiric lore and is often depicted in a humanoid form. The word translates to “leap upon,” with the beast often jumping upon the back of its prey, sometimes growing in size after it attaches itself to their body. The Aufhocker’s main attack was to tear at the throat of humans, embedding its vampire-like teeth and ripping out the flesh. It cannot be killed, although deterrence that work on vampires such as church bells or sunlight are said to work on Aufhockers as well. Even swearing profusely has been said to keep Aufhockers away.

In The Witcher: The main reason to associate Dettlaff with the Aufhocker is because in nearly every encounter the main antagonist and other higher vampires have with Geralt, they targets the throat specifically, digging into the flesh and tearing out pieces. Dettlaff is clearly labeled as a higher vampire, and vampires tend to go to the throat, but the insistence on tearing at the flesh is akin to the Aufhocker’s infamous attack. He shapeshifts as well, the most terrifying iteration being the eye-less, winged beast he turns into if you happen to injure him enough, as he uses bats as tactical weapons from the sky. Like the Aufhocker, he cannot be killed, but with one exception. If a fellow higher vampire were to deliver the last blow, then he would finally lose its immortality.

Umbra

In Folklore: The word umbra originates in Latin, meaning shadow. In mythology, the word is also associated with a shade, which is simply a deceased spirit or ghost residing in the afterlife. Combining the two meanings, an umbra would be a spirit cast into the shadow of the underworld. Shades appear in two famous works of antiquated literature, The Odyssey and The Aeneid. Homer sees shades during a vision of Hades, even talking to his mother’s spirit whom he thought was still alive. Aeneas calls the spirits he encounters after crossing the river Acheron shades, and this text inspired Dante Alighieri to refer to spirits as shades in the "Inferno" portion of his epic poem, Divine Comedy. For Dante, they are phantoms who lack both a body and the ability for thought. They eternally wait along the shore of the river Styx (in the classical Greek texts it’s the river Acheron), hoping to gain passage from the ferryman Charon into the kingdom of Hades. Even Dante’s guide Virgil, named for the author of The Aeneid, is referred to as a shade. In the Polish version of the game the umbra is called a zmora, which is akin to the female version of the alp, the mara/mare. The mara is also closely associated with the horse, said to ride them from night until morning until they were sweaty and exhausted. In Polish folklore they are the souls of living people who travel during the night, and can take on the shape of straw, hair, or moths.

In The Witcher: When Geralt encounters a hermit having restless nights, he is told a monster haunts her but is invisible to humans and witchers alike. The only way to see the apparition is to drink a brew of previously thought extinct greytop mushrooms. Dead moths lie outside the hermit’s home and Geralt notes this happens when there is a phantom nearby, but it’s interesting that the mara is also closely associated with moths. Thanks to the now communicative Roach, the two spot a luminous horse, its blue body decorated with intricate patterns and its mane is fire orange. They learn the horse is actually the troubled spirit of a knight who flogged his own mount to death due to it bucking him off in a tourney. The bestiary states, “An umbra is merely an unclean conscience, one tormented by guilt and unforgiven wrongs.” This umbra had returned to his mortal love the hermit, seeking her forgiveness for his evil deed, unknowingly appearing to her in the shape of a horse. Like in mythology, umbra’s are simply spirits. However, in the Witcher universe they are directly tied to the guilt they feel about the misdeeds they committed during their time on earth.

Blood and Wine fills its world to the brim with monsters similar to the real-life lore of our own mythological history. The new creatures combine both a historically consideration and a new creative outlook for their implementation in the game, allowing any mythology buff to see immediate similarities. Which new monsters did you most enjoy in Blood and Wine and why?

For more on Blood and Wine, read our review.

Get the Game Informer Print Edition!

Explore your favorite games in premium print format, delivered to your door.

- 10 issues per year

- Only $4.80 per issue

- Full digital magazine archive access

- Since 1991