Our extra-large special edition is here. Subscribe today and receive the 25% longer issue at no extra cost!

Behind The Wizardry: Our Interview With Stern Pinball

Last week, I posted a story about Stern Pinball and the company’s thoughts on digital pinball. It was pulled from a much larger conversation I had with Stern’s director of marketing, Jody Dankberg. Today I’ve got the rest of that interview, where we take a deeper dive on pinball as a whole. We cover topics including the process of designing and troubleshooting new tables; what makes a great game from a bar-owner's perspective; and why bands are so eager to get involved in pinball.

“I’ve never met anyone who doesn’t like pinball, but I have met lots of people who say, ‘Oh, wow, I didn’t know they still made those,’ or ‘Where do you get one? Where do you play one?’” Dankberg says. “That’s exciting to me because it’s something where people always get a big smile on their face and most people have a fond memory of it, so it’s a really neat opportunity not only to promote something fun, but we get to work with all sorts of cool licensed properties – anywhere from rock bands to big sci-fi movies to big brand names like Ford Mustang, that we’re working on now.”

Band Recognition

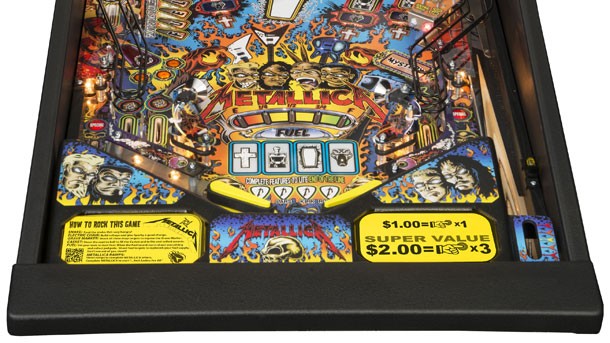

Dankberg comes from the musical-instrument industry, working with guitars and amps, while also maintaining artist relationships. It seems like a natural transition to his current role at Stern, considering the frequency that the company works with bands including Metallica and AC/DC. I asked about the relationship between musicians and pinball, as well as the role of licenses as a whole within the company.

“Music and pinball go really, really well together,” Dankberg says. “I have a lot of relationships in the music business, and it’s really hard to find a band who doesn’t want their own pinball machine. Most members of these bigger bands, the iconic bands, are of the age where they probably grew up with pinball. All of these guys are super rich, so they’re not doing it for the dollars, they’re doing it for the trophy of having a pinball machine. Oftentimes, people look at it as a halo or a vanity project, because [the results are] a cool pinball machine. J.J. Abrams, when we made Star Trek, said, ‘You know when you have your own pinball machine, you’ve really made it.’”

Working with bands also gives pinball designers creative freedom that they might not otherwise get working with other license holders. Players have expectations going into a game based on the latest Star Trek movie, for example, such as missions and thematic elements that evoke the film’s basic plot. Bands bring their own unique style and music to the table, so to speak, but they also let designers’ imaginations run wild.

“That’s what’s really cool about doing a rock band, because there is no good guy or bad guy – there is no lore or missions and stuff,” Dankberg says. “Doing these rock bands, they’re kind of like original titles in that the gameplay is all up in the air. There’s no specific storyline to stick to, and that’s another cool thing about doing the music games. Like Metallica; what do you do? You take some iconic stuff from Metallica, and you make your own world. The same with AC/DC. That is the closest that we get to an original title as far as gameplay goes. … In the case of Metallica, we got to work with the band, they did custom speech on the game, they had a lot of input about what went in the game. They’re big pinball fans, and we got to work with an artist they recommended, a guy named Dirty Donnie, who did all this hand-drawn artwork for the game, which was something that we hadn’t done in a long time.”

Pinball Wizards

One of the things I’ve always been interested in was learning more about how pinball tables are designed. Like any creative pursuit, there’s no template for how table designers work. Dankberg walked me through the general process, starting from conception, engineering, testing, and revision.

“It’s a long, long process,” he says. “It almost starts with the design of the machine. What will happen is the designers will come up with all their concepts, they’ll sketch out their playfields in either solid works or CAD, they’ll work with the mechanical engineers, and the electrical engineers to bring the thing to life. Then they’ll come up with what’s called a white wood. The reason they call it a white wood is because it’s the first iteration of a game and it doesn’t have any paint on it – it’s just a piece of plywood. This is really where the first playtesting begins. This is where the designers can see if what they thought was a good shot is a good shot, test the flow, test where the parts are going to be placed. At the same time, there’s a lot of mechanical testing going on. For example, every time we make a game, we make a new mechanical device, right? There’s no spaceship that shoots pinballs or there’s no guy in an electric chair that makes himself jolt around, right?

“In our mechanical-engineering department, you’ll see a lot of what we call life-cycle testing. We’ll shoot a ball at something a million times or we’ll make a ramp go up and down a million times. That’s going on concurrently with the white-wood testing, making sure that the devices work properly, and they’ll work for a long time, and also making sure that the shots come together. At that point, we’re going into production, because everybody says, ‘OK, cool.’ Once the games come off the assembly line, the playfield goes on what’s called a rotisserie. The reason that it’s called a rotisserie is because if you’ve ever had to work on a pinball machine, they’re quite heavy, so lifting up a pinball machine up and down is very tedious. The way we test the table is we put it on this rotisserie and we’re able to flip the thing around in a circle and they can work on the top and the bottom very quickly. We plug it into our diagnostics system to make sure that all the coils and switches and lights are working. And this takes place for about an hour or two hours, where they’re really fine-tuning all of the device.

“Really, there are only three things on a pinball machine: lights, switches, and coils. Once everything is fine-tuned and adjusted, we’ll place the playfield in what I call its home, and it’s going to live in this cabinet, and it has its own CPU and everything like that. Once it gets to the final assembly, they’ll actually do all those same tests that they did on the rotisserie again, so another couple of hours, and then, believe it or not, there are guys who will play the pinball machine for 20 or 30 minutes to make sure everything’s working properly. It sounds like a fun job, but I tell you, once you’ve playtested a game about a thousand times, it gets a little tedious – but you get pretty good at it. They’re rigorously playtested. It’s a series of checks and balances, because there are 3,500 parts that go into this game, and if one thing’s wrong the whole thing doesn’t work. That’s no fun for anybody, and we’re in the business of making things that are fun. There’s a lot of checks and balances that go into it. It’s a long process; it takes about 30 hours for a pinball machine to make it through the factory, and it also takes about nine months to a year to design a pinball machine and north of a million dollars. They’re big projects.”

What happens when something does go wrong? Since pinball tables are physical objects, coming up with solutions isn’t a matter of fixing lines of code, as you would while debugging a video game. Instead, engineers have to come up with on-the-fly fixes that require a special sort of ingenuity.

“Sometimes you have a game that performs really well on the white wood, and then you get to the production stage and something happens, where it flies right down the middle,” Dankberg says. “What happens with that? You fine-tune adjust. I believe it was either Avatar or Tron had an issue like that, where the ball would come out of the pop bumpers and come straight down in the middle, and what the team did was, on the fly – we call this a running change – they created some type of spring that the ball would reflect off of so it wouldn’t go straight down the middle.

“You want a good balance of where the ball goes. You want it to go down the left side, the right side, down the center a proportionate amount of times. You want people to have fun, you want the game to be what we call ‘mean,’ because you don’t want somebody to be playing for 45 minutes, but you definitely don’t want the ball going down the middle every time with nobody having any chance to hit it.”

While collectors might be attracted to flashy modes and special extras, commercial operators are primarily interested in one thing: making money. They want tables that are reliable and keep players interested (and paying). I asked Dankberg what a typical bar owner is looking for in a new table.

“They want a game that’s going to be one to two minutes, maybe two to three minutes. They want someone to have a good time, but they also want them to put another quarter back in. They want ‘em to almost get some of the good stuff, but almost get there. ‘Oh man, that was close. I’m going to put some more money in.’ They also don’t want the game to be so easy for a guy who’s a world-ranked player where he goes in there, he puts in 25 cents in, and he’s playing for an hour and a half. At that point, the game is not making a lot of money. You don’t want it to be too hard, and you don’t want to be too difficult. You want it to be easy enough so that it’s approachable for a novice, so they have fun and they want to keep putting money into it, and you also want it to be challenging enough for an expert player, too.”

Stern sells several models of each table, aimed at commercial customers and collectors, and they each have their own unique requirements. That means a lot of extra work for the designers.

“Different designers work differently,” Dankberg says. “Some guys start with the lower-end model and then add on, and then maybe in their head they have a concept of what they’re going to do. Other designers do the complete opposite – put everything and the kitchen sink in there, see what works, and then scale back for the commercial models. In reality, they’re really designing two machines, because if something’s missing, you have to fill it in – either with rules or lights or some type of symbolic thing. And if you’re padding something, it really needs to do something. You can’t just say, ‘I just added this,’ and then blink the light.”

What’s Next For Stern?

It seems like we’re in a bit of a pinball renaissance lately, with a thriving collector market and a lively virtual presence from software developers including Farsight Studios and Zen Studios. Dankberg agrees, and he sees additional growth from the same aspect of the business that helped keep the company afloat.

“It was the export business that really carried Stern through a lot of tough times. The reason being, our export business is far more commercial related than our U.S. business,” he says. “When I say, ‘commercial related,’ we’re talking about games going on the street, being operated for money. In export, there’s still a big culture – especially in Western Europe, Australia, South America, the U.K., some far east – where playing on location is still very prevalent. We are seeing a rise in collectors in our export market as we become more of a world economy and everybody knows exactly what’s going on everywhere. Our export customers are now starting to resemble our U.S. customers, because again of the world economy. And then we have certain markets that are completely foreign markets for pinball, and really fun for us to develop – we’re talking about China, India, stuff like that, where there’s never been a pinball culture, so there’s a really huge opportunity for commercial pinball there, and those are some things that we’re working on as well.

“Let’s use China as an example. There’s not really a pinball culture in China, but there is a gaming culture in China, so you tap into that. ... A game that’s very popular there is the Pop A Shot, which is [shooting] that little basketball into the hoop. They have tons of these really high-stakes tournaments, so they’re familiar with tournament culture. It’s a matter of educating them on how to play pinball, which can be daunting because it’s not a very easy game to understand, but once you educate them and start to get them into the culture, they don’t have the decades and decades of culture like we have. We’ve all grown up with pinball, we’ve seen it in the movies, we’ve seen it in home locations, we’ve seen it at the pizza parlor when we grew up, we’ve seen it in the Laundromat – they don’t have that culture yet.”

Reissues are also part of the company’s future. “We’re reissuing our Iron Man pinball machine with what we’re calling our Iron Man Vault Edition,” Dankberg says. “It’s not the first time we’ve ever brought a title back, but this is really going to start a tradition of doing this. Iron Man was a game that we made in 2010, and at the time, the company was much smaller and the market was much smaller. We only made about 1,100 units of the Pro model. It has since become a super cult classic. The used prices were through the roof, and we still had commercial customers and collector customers repeatedly over the past four years requesting this title, so we worked out a deal with Marvel and they’re shipping next month. I would not be surprised to see other Vault Editions – I don’t know exactly what they might be. That’s something we’re getting into right now. We also often have requests for Stern Electronics, which was the company before Stern Pinball; Gary [Stern, Stern Pinball’s founder]’s father [Sam Stern], had a lot of classic tables in the early ‘80s, like Sea Witch and Meteor and Galaxy, and all sorts of fun stuff like that. They’re more of a simpler game but they’re fun games and collector pieces, and we’ve also gotten a lot of requests to [reissue] stuff like that. Who knows? Maybe we’ll do something like that in the future.”

Get the Game Informer Print Edition!

Explore your favorite games in premium print format, delivered to your door.

- 10 issues per year

- Only $4.80 per issue

- Full digital magazine archive access

- Since 1991