Critical Mass - Do Companies Put Too Much Stock In Metacritic?

Video games may be our favorite hobby, but it’s a business. It’s big business for the people that make the games, and it’s also a business for the media who review and rate video games. Whether or not you write for a magazine or website, we all have opinions about how good or bad a title is. But to some it’s more than an opinion; it could be life or death. The competition is tougher than ever today, and not only making, but selling a successful video game makes and breaks the fates of developers large and small.

How do you gauge if a game is successful? Overall quality? Sales? Reviews? For a publicly owned publisher, for instance, you’d think sales are the one and only figure that matters. Sales are undoubtedly important. However, another factor is arguably just as valuable to the marketing departments, accountants, executives, shareholders, and development teams behind these multi-million dollar projects: public opinion. More specifically, the scores calculated by aggregate review score sites such as Metacritic and Game Rankings.

What does a site like Metacritic, which takes a swath of review scores for a game, interprets the different scoring systems, and squeezes out a single unified score, really tell anyone? Is it fair to judge a game based on such a system? How does it affect the attitudes and practices of companies and the teams that make the games? Regardless of your answers to these questions, companies like Electronic Arts are paying close attention to what Metacritic says about its products.

“It’s definitely something that pushes us, motivates us, and makes us work harder,” says Glen Schofield, former Visceral Games general manager and Dead Space executive producer.

Under the Hood

Metacritic gives games a Metascore based on a 100-point scale, with titles scoring 75 or above receiving a green banner to indicate to consumers it’s a good game. Outlets that don’t grade on a 100-point scale have their scores converted by Metacritic, including those that don’t assign a review score of any kind. Metacritic draws from a host of close to 140 different outlets to determine which will be utilized for a Metascore. Which ones it chooses is something that co-founder and games editor Mark Doyle says he decides himself. In fact, Doyle told us that half his time is devoted solely to trying to keep up with who’s good enough to contribute to a Metascore. “You can’t automate this process,” he says. “You really have to pay attention, because there’s a lot of really weird stuff that goes on.”

Metacritic has drawn criticism because of how it converts review scores into its own Metascore, including grade-based reviews from sites such as 1up.com. Editorial director Sam Kennedy believes that it’s potentially dangerous to take a review out a magazine or site’s overall context, and that their move to a letter grade system was done because they thought it would be better understood. “The unfortunate thing,” he says, “was that the only people who didn’t understand that were some of the aggregators.” Kennedy says that they’re working with Metacritic to come to a better understanding, but that right now a 1up.com B- translates into what Metacritic considers a mixed review, while Kennedy says that they think a B- is still in the good range.

Metacritic’s Doyle disagrees that letter grades are necessarily universally understood. “I find it the complete opposite. If you give something an F it’s totally worthless, so why put it up against everyone else’s 50 or 58 like it is in school?”

While there is no absolute way to infallibly convert grading scales or come to total agreement, to developers like Glen Schofield, the effects are very real. “Dead Space on the Xbox 360 had 78 reviews. 51 of them were 90 or above, but we got an 89 as our final score. We only had one 65 so…how do you get 51 that are above 90 and end up with 89? That brought us down one point. The difference between an 89 and a 90 is a big ass deal.”

It's Not Just a Game

How big of a deal? It can put a lot of pressure on the entire organization, from development teams to marketing and public relations. Some publishers tie a game’s Metacritic score into the dev team’s bonus money, and high-level decisions can be made before a game’s release depending on what that company anticipates the Metacritic score to be. Maybe a company plays it safe with a game so as not to risk a lower score at the expense of taking a chance on a possibly cool, but risky, direction. Some teams are forced to gauge the time and money needed to implement a feature against what it may or may not gain them in Metacritic points.

Sales would surely seem to be more important than an aggregate review score. Some believe there is a tight relationship between the two, but that isn’t always the case. Some rumors have circulated stating that some industry analysts have used a Metacritic score, for example, to change their outlook of a publicly held company’s stock before the real sales data rolled in. A bad score on an otherwise fine game could scare off potential buyers, thereby lowering sales numbers.

Finally, there is the argument that sales, scores, and other outside artificial benchmarks can pollute the artistic vision of the creators, and therefore the games themselves. This question of subjectivity occurs from the nature of reviews, opinions, and scores such as in this magazine.

“I made a game quite a few years ago,” Schofield tells us, “and it was about six months later and a reporter was asking me, ‘Well, why didn’t you ever make a sequel? I loved that game!’ I said, ‘Dude, you gave it a 70, so based on those reviews, we didn’t do another one.’ And he was like, ‘Oh yeah, that’s right, I did.’”

Schofield says Electronic Arts doesn’t have a defined policy regarding Metacritic scores, and he would not talk about whether the company ties employee bonuses to such scores, but he fully admits the effect it has on a development team.

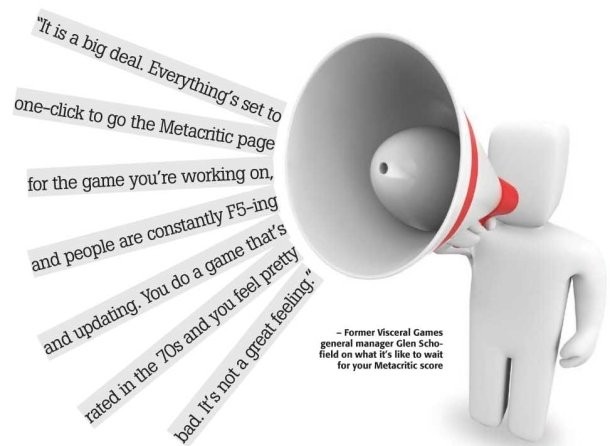

“It is a big deal. Everything’s set to one-click to go the Metacritic page for the game you’re working on, and people are constantly F5-ing and updating. You do a game that’s rated in the 70s and you feel pretty bad. It’s not a great feeling. I know when scores were coming in for Dead Space, people were yelling, ‘It just went up a point. We’re up to 16th!’ They were looking to where we are overall, and it’s a huge deal. The first few weeks are really, really exciting when it comes out.”

Discerning Voices

Schofield has his own idea of how to tweak the system to make it better: Throw out the highest and lowest score used to create an aggregate review score. This would help eliminate any extreme bias for or against a game and possibly create a more realistic average. Publishers could just do this themselves, but such internal judgments don’t seem to be occurring. Companies could also be more self-selective about what opinions they decided should matter in an attempt to tune out some of the static. Schofield says that in the case of Dead Space’s near-miss of a 90 Metacritic rating, it turned out that the game’s lowest score was from a freelancer that a particular magazine had hired. This made him question the score. “They just picked up a freelance person and he or she did a review on it, and so, you know, I wonder, why would we give so much weight to that? Maybe that person’s favorite games were sports, and maybe shouldn’t be doing this kind of game.”

Choosing context and what opinions to heed and ignore can be a dangerous way to drink your own kool-aid, but companies are starting to get smarter about aggregate scores. EA Sports’ Peter Moore says that factors such as a game’s genre and platform need to be taken into account, citing the extenuating circumstances regarding traditionally lower scores for Wii games and the fact that these don’t always match up to those titles’ higher sales. Moreover, EA CEO John Riccitiello believes that factors such as a game being a sequel or polarizing because it has already established fans and non-fans (like the Sims) must be weighed.

In the end, Schofield believes that the importance of Metacritic will remain. “We need a judge to tell us how good we are, and I believe that the consumer needs something that says whether a game is good or not. I’m always going to be looking for a way to judge myself and judge our games against our peers and competitors, and we always want that Holy Grail: good scores, DICE awards, and all that good stuff. It validates your hard work. You’ve been working two years or whatever on the game, and you want someone to tell you that you did a good job. And if not, it pushes you really [emphasis his] hard for the next one.”

With the importance of aggregate scoring a constant for the foreseeable future, perhaps all that can be done is for companies to get smarter about reading the Metacritic tea leaves, and media outlets to publish quality reviews so that the hard work of developers like Schofield is not in vain.

Get the Game Informer Print Edition!

Explore your favorite games in premium print format, delivered to your door.

- 10 issues per year

- Only $4.80 per issue

- Full digital magazine archive access

- Since 1991