Please support Game Informer. Print magazine subscriptions are less than $2 per issue

Five Of Our Favorite Hidden Stories In Games

Some of the most intriguing stories in video games aren’t told directly to the player. You can make it to the end of Dark Souls with no grasp on an overarching plot – left only with the thin narrative thread of surviving brutal boss encounters with sparkling bonfires in between. Some tales can only be read between the lines.

A lot of the time, it’s possible for stories to hang out on the sidelines because there are other factors drawing the player to the end of the game. Poorly constructed plotlines fall to the wayside while an alluring progression system draws the player to the end of an RPG. Some fighting games lay character backstories to rest in the pages of a manual in favor of sound fighting mechanics.

As it turns out, these sparse nuggets of storytelling end up sparking passionate fan theories and wild speculation. Are you still searching for answers to why you’re on a strange puzzle-filled island in The Witness? Have you been disassembling Undertale to uncover the mysteries of W.D. Gaster? Do you lie awake at night wondering why the G-Man stalks you in Half-Life 2?

Our minds definitely race with these possibilities, and here are some of our favorite hidden stories in games (spoilers ahead).

Braid – The atomic bomb

On its surface, Braid looks to be a painterly take on Mario’s damsel in distress story. A widely accepted theory is that Tim, the protagonist, isn’t racing to rescue the helpless princess. Instead, the princess can be interpreted as a metaphor for the invention of the atomic bomb.

Braid’s narrative is dealt out in storybooks placed in between levels, which all have slices of exposition. Fans stitched together this theory when they noticed that some of the quotes in the storybooks were from people involved with the invention of the world’s first nuclear weapon.

In the epilogue of the game is a quote from William Laurence, the only journalist allowed at Trinity – a codename for the first test nuclear bomb detonation. Laurence writes:

“On that moment hung eternity. Time stood still. Space contracted to a pinpoint. It was as though the earth had opened and the skies split. One felt as though he had been privileged to witness the Birth of the World…”

The storybooks that follow talk about how the princess “stood tall and majestic,” and how she “radiated fury.” Further evidence supporting the atomic bomb metaphor comes from other Trinity quotes in the story, and if you manage to touch the princess in the final sequence she explodes in a flash of light.

Jonathan Blow himself has all but confirmed that this theory is true, but he claims there’s more to Braid’s story than just that. "I'm not really talking that much about the story, but [that quote is] most certainly in there. It's something to take into account when reading the text,” Blow said at Nottingham’s GameCity Festival. “But how much does it come into the actual story? It's a very tightly focused game, I spent three years working on details.”

Jonathan Blow's latest game, The Witness, has some equally compelling mysteries embedded in its story. You can read our thoughts on Blow's latest brain teaser here.

Portal – Rattmann dens

When Portal released in 2007, the phrase “the cake is a lie” became inescapable. GLaDOS, the evil core-A.I. that guides Chell through Aperture Science’s testing chambers, promises all test subjects that cake is waiting for them at the end of their trials. Doug Rattman was the first person to realize that something was off with GLaDOS’ morality core.

Rattmann is a paranoid schizophrenic ex-scientist at Aperture science. As Chell escapes from GLaDOS’ insane clutches, she comes across various hidden dens where Rattmann wrote warnings with barely coherent doodles. The dens, which are often behind a grate or mangled wall panel, are freshly lived in. “The cake is a lie” is written over and over. Boxes with the Aperture logo become beds as the environmental storytelling implies that Rattman is seeking refuge from an all-seeing robot that would make HAL 9000 blush.

Rattmann’s involvement in the first Portal is confirmed by more detailed drawings in Portal 2, which explicitly show events from the first game. These drawings depict the mass-murder of Aperture’s employees at GLaDOS hand, and they confirm that Rattmann was closely following Chell with a companion cube that he thought was sentient.

Whether Rattmann is alive in the second game is up for debate, but we do know that Rattmann ended up saving Chell’s life by extending her cryogenic slumber after Party Escort Bots brought her back into Aperture Science’s facility in the wake of GLaDOS’ explosive death.

Rattmann’s insane scrawlings were a watershed moment for graffiti-based storytelling in games, and many more tried to imitate the effectiveness of letting the player stumble across tales embedded in the environment.

We delved deep into the development of Portal 2 with our cover reveal back in 2010, and there are compelling stories to be read at our Portal 2 hub.

Wolfenstein: The New Order – Ramona's Story

Wolfenstein: The New Order keeps its surprises tucked away deep in its Nazi-killing layers. It’s easy to view the game as another alternate-history tale with no emotional depth, but that’s only an outsider’s view. As we pointed out around the game’s release, there’s a hidden humanity to Wolfenstein.

Anya Oliwa is B.J. Blazkowicz’s intimate partner in the game. Their relationship was initially meant to be kept strictly professional. Throughout the game Oliwa and Blazkowicz open up to each other and become lovers.

Halfway through the game, Anya tells B.J. that she obtained a diary that belonged to her cousin Ramona. The story unlocks incrementally, and each passage in the diary is voice acted with nuanced emotion. Ramona’s diary charts her evolution from an oppressed war victim to a vengeful Nazi killer.

Ramona’s town is taken over by Nazis during their Polish invasion, and her anger seethes after the violent occupiers killed her lover. She notes in her diary the moment she hatches a plan to kill them. Ramona writes:

“May 12, 1940. The Nazis have taken over the police station. They are asking local people to volunteer for service. I'm going to volunteer. I'm going to find a way to kill them.”

Ramona builds up the courage to kill her first Nazi, and is rattled by the soldier calling out for his mother while being murdered. She pushes her emotions away by thinking of her past lover as she kills more Nazis, and tragically gets impregnated by a soldier that she later strangles. She considers herself a soldier by taking revenge on her occupiers, and newspaper clippings in the game’s environment talk about a serial Nazi-killer.

The final entry heavily hints that Ramona is actually Anya, and her diary was a way of sharing her troubled, guilt-ridden past with B.J.

It’s a small pocket of emotional storytelling that can easily be missed, and is indicative of Wolfenstein's nuanced storytelling.

To find out why Wolfenstein: The New Order was surprising in more ways than one, check out our review.

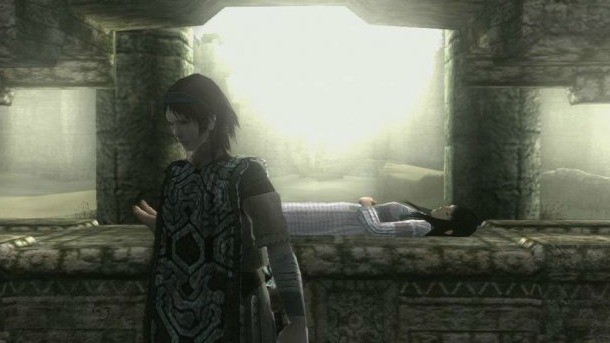

Shadow of the Colossus – Wander and Dormin

Shadow of the Colossus lets you sit with your decisions. A booming, ominous voice is the only semblance of speech in the game, and besides that, you’re stuck in silence. You wordlessly roam from one hulking Colossi to the next.

Wander travels with his loyal horse Agro to kill the 16 Colossi. He is motivated by Mono, a dormant lover who has fallen to a curse. If Wander destroys all of the ancient beasts with his stolen Ancient Sword, then he would be allowed to resurrect her.

On paper, this story may seem brim with clichés, but the fact that it’s communicated with almost no dialogue makes it a unique, emotionally impactful experience. After scaling the furry husk of a giant ancient being, you sympathize with it as it wails after you drive your sword into its glowing weak point. It makes you wonder if you’re doing the right thing; after all, you’re killing creatures that are completely peaceful until provoked.

It turns out you’re kind of a jerk for doing it, and resurrections carry a hefty price. In the final sequence of the game you realize that the ancient booming voice telling you to murder the Colossi may have had ulterior motives.

After killing the final Colossus, you are consumed by the dark being that compelled you to leave a trail of gigantic bodies. The princess is resurrected, but you have been reduced to an infant with horn-like nubs protruding from your forehead.

This is a shocking and memorable end to one of the most atmospherically complete games of the PS2-era. Seeing Wander lose everything to resurrect his fallen love puts a new spin on the damsel in distress story, and the player is left wondering if the ancient darkness has once again been unleashed across the land. Shadow of the Colossus is not only remarkable for its unique way of crafting a narrative, but it has many other qualities which make it one of our essential games to play.

Dark Souls – Artorias and Sif

Out of all the games on this list, Dark Souls tells its story in the most indirect fashion. Every character is on the brink of insanity and speaks in cryptic sentences, and most of the story is told through item descriptions. It’s an incredibly bleak game, and when you put a magnifying glass to its mythos, nobody gets a happy ending.

Artorias of the Abyss is a piece of DLC for Dark Souls, and tells a gripping story in one of the most obtuse ways. Everything about Artorias and his wolf companion Sif is obscured by a layer of mystery that the player has cut through with sporadic clues.

Even access to the additional content containing the Artorias subplot is hidden. You have to go through a laundry list of fetch-quest objectives to enter Oolacile, a land that exists in a time before the events of Dark Souls. Time in Dark Souls is convoluted and distorted, so time travelling isn’t outrageous.

The Knight Artorias and his wolf-pal Sif went to Oolacile to save Princess Dusk, but the people Oolacile were completely consumed by a dark force known as the Abyss. While being overrun by enemies, Artorias sacrificed himself to protect Sif by laying down his greatshield.

Much like Shadow of the Colossus, killing Sif the Great Grey Wolf should make you feel bad about yourself. When you come across Sif in the main storyline, the hound lunges as you approach Artorias’ tombstone, picking up Artorias’ Greatsword to battle you with.

It’s a subtle piece of storytelling, but if you’ve faced Artorias before you’ll notice that Sif shares a similar moveset. Also, if you happened to kill Artorias before your encounter with Sif, you’ll be treated to an alternate cutscene. Sif pins you down and sniffs you, sensing that you’re the one responsible for killing their companion.

The story of Sif and Artorias is emblematic of how powerful and hidden the storytelling in the souls series can be. It’s something that you can completely miss if you’re not trying to assemble a narrative from clues in the environment.

If you want to watch editors Tim Turi and Dan Tack bash there heads against Artorias, check out Super Replay. Dark Souls III looks to have similarly obscure storytelling techniques, and you can head to our hub to get more information on the upcoming From Software title.

Games are constantly disassembling and repackaging how stories are told, and if you liked hearing about our favorite hidden stories in games then you should check out the epic sagas contained in our list of gaming's longest continuous stories. Also, read this excellent feature exploring how developers wrap up their narratives in The Art of Endings: Tales Of Ending A Game.