The Art Of Endings: Tales Of Ending A Game

Endings are tricky. A good ending can resonate with you long after you’ve finished an experience and live on in your conversations and memories. However, an unsatisfying one can cast a cloud over an otherwise solid story. So much can hinge on a finale that writers often struggle to bring everything together to leave a strong statement. Writers across all media can relate to the dilemma, but video games present a unique challenge.

[This feature originally appeared in Game Informer issue #249]

Decades ago, many cared only about one thing: playing the game. Games like Super Mario Bros. started with just pure gameplay, throwing you into the game without any story beats. Only later did you realize you were rescuing a princess. It was about the fun and the challenge of platforming, not what the ending would reveal.

As the nascent industry grew, games started venturing further into narrative with character development, overarching themes, and full story arcs, making endings a bigger deal. It makes sense; an ending is the last thing the player is left with, a culmination of everything achieved in a game, and where the story reaches its shocking reveals and resolutions.

Developers are getting even craftier and experimenting with new techniques, which has led to the explosion of creative approaches we’ve seen over the past year. Are you still trying to figure out what Ellie’s last statement meant in The Last of Us? Have you pieced together everything in BioShock Infinite? Are you still haunted by that final scene in The Walking Dead? Maybe you’re still echoing your disappointment with Mass Effect 3’s ending on forums. The point is, gamers are talking about endings more than ever. They clearly have power, whether it’s to evoke emotion or sour an entire experience. So, just how difficult is it to deliver a satisfying end for a video game?

A lot harder than you think.

Note: We were careful about spoilers, but details about different game endings are brought up in this article. Discussed games include The Last of Us, BioShock Infinite, Deus Ex: Human Revolution, Gone Home, Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons, and Braid

The Difference With Games

Unfortunately, developers can’t just devote all their time to story. While other forms of media are passive experiences, developers must always consider what a player is doing. Cutscenes can’t go too long, and interactivity needs to be the driving force whenever possible, even during the ending. Ken Levine and Irrational Games had to overcome this challenge when executing BioShock Infinite’s final moments where Elizabeth enlightens Booker.

“You have a very narrow gauge of storytelling compared to a book or movie, because long scenes with people talking to each other are really tricky,” says Irrational Games co-founder and creative director Ken Levine. “The whole ending we could have had as a cutscene with people talking to each other. Elizabeth could have explained everything, like her and the tears and the lighthouses, but we had to make that whole sequence interactive. That was really tricky because it wasn’t just complicated from a development standpoint, but it was also conceptually a complicated notion.”

|

The Last Of Us’ Infamous Last Word Naughty Dog creative director Neil Druckmann didn’t always plan for the game to end on the word, “Okay.” Ashley Johnston, Ellie’s voice actress, would often inject the word unscripted into Ellie’s interactions, which got Druckmann thinking about how it would make an impact for the finale. “I thought it would be interesting to take that simple word, but the way she would play it would have such a different subtext, and people could interpret it in different ways, even though in our discussions she played it in a very specific way,” Druckmann says. “In the whole game we tried doing this, having dialogue that doesn’t tell you much about how the characters feel, but it’s more about how you’re going to read them and their expressions and delivery about how they truly felt about something.” |

The ending Levine tackled dealt with quantum mechanics and string theory, so the interactivity of walking you through the concepts as Booker was essential in making players grasp these challenging notions. Levine’s team presented the many-worlds theory without a hitch by showing all the different interpretations of the lighthouse and the world surrounding it. The “constants and variables” not only tie the story together for Infinite, but deftly ties Infinite to the original BioShock’s world of Rapture.

To make sure these interactive tales work, though, writers must be in constant contact with level designers. Naughty Dog creative director Neil Druck mann found out just how much of an asset this could be when working on the final moments of The Last of Us. Remember that hospital scene where you’re carrying Ellie that harkens back to the game’s opening? Originally, that was one big cutscene from the moment you entered the hospital. “There was one designer, Peter Fields, who kept arguing that that sequence should be playable, and he was right,” Druckmann says. “Even though that scene was already being animated, we threw it away and reworked that sequence to make it playable.”

The studio’s stressing of interactivity also helped establish another key moment to the The Last of Us’ ending. Did you resonate more with Ellie’s point of view than Joel’s as you entered their final conversation of the game? It was deliberate. Druckmann shed some light on it, saying, “I don’t think the ending conversation with Joel and Ellie would work outside of a cinematic for us, but the whole walk-up to that point, you’re playing as Ellie, now emphasizing as Ellie, and you’re viewing Joel now from the outside,” he says. “We’re using interactivity to give you a certain perspective. I think a lot of players enter that scene with the viewpoint of Ellie, kind of looking at Joel [saying], ‘What have you done?’”

One of the more successful interactive experiences achieved in an ending recently was Starbreeze Studios’ Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons. Director Josef Fares made it a point to put interaction front and center and thinks it helped make his ending mean more to players. “If the ending of Brothers happened in a cutscene, people wouldn’t react at all,” Fares says. Fares twisted the way players experienced an ending by making the controls play into a young boy dealing with loss, but not everybody was instantly onboard. “From a technical perspective, people were like, ‘Can’t we do this as a cutscene?’” he says. “But for me, no. The interactivity is extremely important for making the player feel something emotional and strong.”

Up next: Getting a glimpse behind the scenes...

Behind The Scenes: Making Endings Work

With publisher demands, development schedules, and last-minute changes, so much happens before we see the ending that gets shipped. Sometimes tough cuts need to be made. Other times, studios scramble to add an element for clarification at the last minute. Every once in a while, epiphanies hit that change how the entire finale plays out. Development schedules are stressful and time is of the utmost importance, so honing endings during the process isn’t exactly the easiest or smoothest venture.

Just ask Deus Ex: Human Revolution’s executive game director Jean-Francois Dugas and narrative design/writing director, Mary DeMarle. The duo had only a week to write the four different monologues and twelve variations for the endings to Deus Ex: Human Revolution. Dugas and DeMarle were prepared for the task, as they both had researched the philosophical angles they wanted to take well before the endings had to be written. “We knew all along what we wanted for the endings, but we couldn’t really crystalize it for a very, very long time,” DeMarle says. Both were heavily involved in other aspects of the game, so they both would work full workdays on other parts before turning their attention to the narrative. DeMarle remembers being in the motion capture studio all day and then meeting Dugas and working from 6 p.m. until at least midnight to get the job done.

Even when DeMarle and Dugas had set their endings, things still had to change. Dugas envisioned much more startling imagery pulled from real historical events to go with the final monologues. “I had much more graphic stuff,” he says. “Not in the sense of gore or anything like that, but we’re going back into the history of mankind. We had more powerful imagery originally in those endings and we had to edit it for the company. I can respect that, but for me from the creator’s standpoint, it was, ‘How do I respect the company without compromising the vision of those endings?’ I worked two months reworking the imagery and going back and forth until we got something powerful that the company was also comfortable with.”

Irrational Games also struggled making all the pieces of BioShock Infinite come together in the end. “I knew what I wanted the ending to be when we worked on it for a long time, but then it was like, ‘Okay, here’s where we want to go. How the hell do we get there in a way that’s going to be clear to the player?” Levine says. He wanted players to understand certain connections, which lead to his idea to give Elizabeth her missing little finger and thimble, but he didn’t have this epiphany until late in development. “Her pinky became a big component of solving a lot of our problems,” Levine says. “If you look at the E3 demo from 2011, she’s not missing half her pinky.”

Naughty Dog’s Neil Druckmann also has experience with last-minute changes, but in his case, it was to take the ending in a different direction. Originally, The Last of Us’ ending wasn’t as ambiguous, with Ellie believing Joel’s infamous lie. “The more Ellie got developed...it felt dishonest to end it that way,” Druckmann says. “It felt that Ellie would be more aware of what’s going on, and as I started writing that final scene, it took on a whole different tone where Ellie challenges Joel and confronts him.”

Even games without blockbuster budgets still need to make changes late in the game. Jonathan Blow didn’t decide on the ending for Braid until nine months into development. His vision also changed while he was creating the game. “I didn’t know what the ending was going to be, but my assumption was that the princess didn’t actually exist,” Blow says. “That was the working assumption that I went with from the start of development: That she didn’t exist. That it was an existentialist kind of situation where she’s always in another castle.”

Blow didn’t settle on that idea, but it informed him in how he wanted to cast the end. “When it comes to making an ending the way that the game actually ended, it’s more like a natural outgrowth of that thought,” he says. “The princess isn’t what Tim expected, and the situation is not what he expected. When he gets wherever he’s trying to go, it’s maybe not what he envisioned.”

Fullbright Company co-founder Steve Gaynor, who helped create Gone Home, has a similar tale. “We did not arrive at the ending we ended up shipping until two weeks before we went into the recording studio to do the last round of voice recording, which is a month and a half before we finished the game,” he says. He recalls having an ending he thought he was going to be happy with, but realized it wasn’t working. “It was a much more melancholy ending,” Gaynor says. “I started writing it and I just wasn’t happy with it.”

From then on, Gaynor wrote a bunch of different endings to see what worked and didn’t. “We went down some of these blind alleys trying different endings. We didn’t keep them, but it gave us material that we ended up incorporating into the game,” he says. One example Gaynor recalls is having Lonnie run off to be in a band. While this didn’t become the ending, it gave him the idea to have Lonnie join a band in the first place.

While Blow and Gaynor were able to change things around much later in the process, bigger budget games often don’t have this luxury. Corey May, a consultant for Ubisoft's narrative talent group who wrote much of the Assassin’s Creed series, says he starts planning for the ending as soon as discussion starts for the games. “You want to avoid not knowing where you’re going, especially when you have finite time and resources like you do with a game,” May says. “If you’re writing a novel you can sit on it and see where it takes you; when you know you have deadline, you don’t want to be unaware or surprised at the end.”

May also says that advanced tech like motion capturing makes tweaking ending moments difficult. “The challenge has always been that we as writers don’t have enough time or as much of a chance to iterate as other people do because of the motion capture pipeline,” May says. “Once that stuff is recorded and then put into the engine, cleaned up, and edited, it’s very hard to go back and say, ‘Well, I want to tweak that or we should change that line.” Once cutscenes are motion captured, they’re often set in stone. “You have to figure out clever ways to get around it, like dropping in additional voiceovers where you don’t have to worry about lip sync, or surrounding cutscenes with narrative information because you can’t go back in and tweak cutscenes,” May says.

Up next: Examining different ending types...

The Art Of Different Ending Types

Each developer may have a different agenda when it comes endings. Some tease a future release, others close out a tale, and many writers prefer to leave things open-ended. As with all creative mediums, the results vary depending on the tactics.

|

Digesting An Ending: Braid’s Epilogue With all the different things going on in endings, is it possible we’re just not properly digesting these larger reveals? Jonathan Blow took a unique approach with Braid by including an epilogue that provided a bit more insight into what happened, giving you plenty to piece together and work through in your head. Blow’s reasoning for including the epilogue is interesting. “There needs to be some space for digesting a surprise,” he says. “Otherwise, it’s like someone just punched you in the face and then it’s over. It’s like, ‘Well…that doesn’t feel very good.’ In terms of the fiction, there needs to be some kind of space if the character had a surprise happen to him. There needs to be some response to that or you’re not letting the character develop or come to a final place.” The epilogue also has some things with the game mechanics going on that Blow won’t spoil because he feels not many people have figured them out. “[They’re] about trying to develop maturity a little bit in the space of solving puzzles,” he says. |

Assassin’s Creed usually goes for two different endings: one that resolves the historical tale, and one that leaves the present-day on a cliffhanger. According to May, the meta-story of Assassin’s Creed exists in studio documents, so the writers are always prepared for what’s coming and can tease that.

“We never knew sitting down that the franchise would grow as large as it did, so I’m really glad that we took the time to establish some rules for our world and the different factions and the different potential events both in the past and the present, so we can draw on that to move things forward,” May says. He also compares Assassin’s Creed’s ending formula to a TV season cliffhanger. “We’ll wrap up the conflict and drama for a given season and then introduce what comes next, but since there is a much longer arc that’s been planned and plotted, it’s easy for us from that. It’s been designed with those peaks and valleys in mind.”

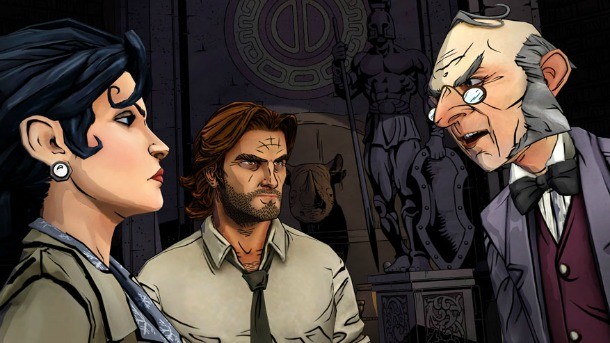

Telltale Games mastered the art of the cliffhanger in The Walking Dead, using it for each episode. Telltale’s newest venture, The Wolf Among Us, is striving to find the same fanfare, but how do you please people with the knowledge you’re going to leave them hanging after each episode? “The hope is that...you come out of it with a level of resolution that makes you feel like, ‘I got my money’s worth and I want more,’” says lead writer Pierre Shorette. “A cliffhanger doesn’t work unless an episode tells a compelling experience,” says director Nick Herman. “You could have an amazing cliffhanger and a bummer of an episode and nobody’s going to care.”

While the cliffhanger is a popular ending technique, there’s no denying the appeal of player choice and multiple endings. These approaches come with a slew of other obstacles. How do you make sure one ending doesn’t overshadow the others? How do you let players make choices that matter, but not judge them for it in how you cast the conclusion? For Deus Ex: Human Revolution, Eidos Montreal tried to include a shade of gray to every ending outcome. “We didn’t want endings that said, ‘You made the wrong choice,’” DeMarle says. “We wanted endings that embraced the good and the bad of the decision and that tried to show you that.”

When adding an element of choice to the narrative, many studios struggle with balancing how much power you put in the player’s hands while still being able to tell an authored story. The Mass Effect trilogy is the most ambitious and controversial of these attempts.

“When we did Mass Effect 1, we wanted to be building a trilogy, but...we weren’t greenlit for a part two,” says BioWare executive producer Casey Hudson. “We didn’t know if it was going to be successful enough to be a trilogy. We wanted [the first Mass Effect game] to feel like the first act – your call to glory. But we also wanted it to be able to stand alone in case we didn’t end up building the other two.”

Once work on Mass Effect 2 started, BioWare knew it would be a full trilogy, so it kept things uncertain to enhance the player's concern for the future. The goal was simple for the third game: resolution. “For 3, we were trying to wrap up the whole trilogy, show you what your story meant, but leave things there for you to think about and interpret,” Hudson says.

BioWare experimented with having player choice span throughout the three games, but the choices available in the final endings didn’t meet many fans’ expectations. This started one of the most raucous uproars ever over a game ending. BioWare learned firsthand the danger of balancing player choice with an authored story. “I think different people have different ideas,” Hudson says. “Even for Mass Effect, many people play the exact same games, but come out with very different ideas to what degree they should be able to see their choices reflected in the story, and to what degree they’re going to see the impact of what they’ve done versus the authored story.”

Hudson recognizes it’s a difficult balancing act, but believes it’s worth the effort. “Our goal is always to put the story in the hands of the player as much as possible, but to somehow also ensure that that story is always going to be a good one,” he says. “The idea of total freedom and choice in the way that the story unfolds obviously do compete with each other to some degree. Our goal is to try and create enough of an illusion of total freedom, while taking you on at least a variety of options that we’ve been able to author and telling a really compelling story. It’s definitely challenging to find that balance.”

Choice and multiple endings are so difficult to nail down that developers are often lukewarm about them; Levine doesn’t want to attempt an ending that embraces choice again unless he knows he can deliver on it. “In BioShock 1 we had multiple endings, and that was the one thing the publisher insisted upon that I didn’t agree with, but, hey, they were paying for the party,” Levine says. “So that time, I was like, ‘I’ll do it,’ but I didn’t want to do it again because I felt like it wasn’t something we could really deliver on, not just as a game, but as an industry, we still have problems delivering on that level of choice in a narrative experience.”

Levine prefers to leave some open-endedness to allow a degree of player interpretation and spark discussion. “My favorite endings are the endings that leave you piecing everything together...where it makes you reexamine everything you saw before and you have to go back through it all and rethink everything.” You can see this in BioShock Infinite’s ending; Levine still gets people asking him for the correct interpretation, which he always declines to answer. “It’s much more interesting to let people imagine what it is, and if I answer it all those conversations would come to an end. I think that would be a shame,” Levine says.

Up next: What's the future hold?

Game Endings: Present And Future

Look at most message boards, and multiple topics arise regarding game endings. Gamers are placing more importance on them than ever, but what is so often forgotten is just how young the art form is. Developers are still trying to figure out how to do endings, and most agree the medium still isn’t where it needs to be for storytelling.

Hudson, who’s working on the next Mass Ef fect game and a new IP, is also trying to figure out a way to combat story issues. “Our main focus is to find ways to tell story in a more free form way, where it’s what you’re doing that is the story, so that the story is always with you. It is as much about total freedom as possible,” Hudson says. “Over time, games have become more and more about the interactivity and the freedom. So, every time you’re showing a cutscene, you’re taking control away from the player to tell an authored story. I think we have to get closer and closer toward always being fully interactive, and through that complete interactivity we are able to tell you a story.”

The focus on interactivity is a hot topic amongst designers. Because of a game’s interactive nature, are endings even what the experience of playing a game is about? Darby McDevitt, lead writer of Assasin’s Creed IV: Black Flag, is not so sure. “I actually almost think that it’s a tragedy so much focus is put on the endings,” he says. “I prefer experimental literature where the endings don’t matter; it’s about the journey. The pleasure is in the doing. I find that has a weird connection with games. If games aren’t fun to play with and within themselves then there’s something wrong.”

Levine thinks so far games haven’t struck gold with stories, but the worlds are part of the magic. "Games do worlds better than they do stories,” he says. “One thing that games can do is immerse you in a space in a way no other media can. But I think we have a ways to go because our narratives don’t allow us the freedom that the gaming experience does or that the exploratory experience does. That can get frustrating for gamers, and I’m not sure how to really solve it. It’s something I’ve been thinking a lot about lately. I have some thoughts, but I don’t have what I would call a plan.”

Druckmann echoes similar sentiments to Levine. “We do have a long way to go, only because we don’t fully understand the language or what stories we’re capable telling within in games. We’re constantly coming up against limitations where gameplay can dictate the types of stories we tell, and sometimes those things are in conflict, but I feel like we’re figuring more and more of that stuff out.”

Developers will continue to experiment and discover new ways to make stories thrive, but endings will always be tricky; that’s a given no matter the medium. It is thrilling that games are evolving in the ways they tell stories, and we’re right in the middle of it. Look at Papers, Please; you do busy work as border control to understand human empathy.

Gone Home co-creator Gaynor sees this experimental time as equally scary and exciting. “We’re in this situation where…we’re still discovering a lot about what works versus what doesn’t with different kinds of games and finding new conventions that haven’t existed before and seeing how other people are doing things for the first time,” he says. “I think that’s a really exciting time to be in, but it also means as a creator, you don’t have as many examples to draw from, so you have to be very in tune with what you’re making and do something that’s right for [your game].”

Ken Levine sums it up, saying, “I think we’re in the Stone Age, honestly. It’s tough when people ask questions like, ‘What do you think of the state of game narrative?’ It has a long way to go to figure out what it is. [In film,] everything had to be invented – the reverse angle shot, the tracking shot – the first films had several years before they came into the idea of cutting in time and spacing, moving from one scene to another. All of those things had to be learned along the way, and we have a lot of learning to do.”

Get the Game Informer Print Edition!

Explore your favorite games in premium print format, delivered to your door.

- 10 issues per year

- Only $4.80 per issue

- Full digital magazine archive access

- Since 1991