Please support Game Informer. Print magazine subscriptions are less than $2 per issue

Letting Players Tell The Story: Simulation Games As Narrative Machines

The settlement began with what can only be described as cautious optimism. The dwarfs made quick progress building their new mountain home during the first year despite the herds of vicious elephants outside. They found an underground stream that allowed them to irrigate indoor farms and began work on some rudimentary fortifications. But there were warning signs for what was to come. Worryingly, the name of the site they had chosen for their new settlement was Boatmurdered.

The dwarfs (who dislike the trendy term "dwarves" popularized by J.R.R. Tolkien) gradually learned to deal with the rigors of daily life, including the hordes of angry elephants who roamed the jungle outside. They built an elaborate mechanism to discourage visitors, which the dwarfs could use to flood the area around the gates with lava from deep within the mountain. In the end, it was this very defense system that doomed Boatmurdered. During one attack, the flowing lava ignited a defensive catapult, which belched smoke into the upper halls for weeks afterward. It proved too much for the dwarfs to handle, and Boatmurdered society quickly degenerated as dwarfs one by one lost their wits or suffocated. Dwarf set upon fellow dwarf, and the body count rose. Madness and violence spread throughout the halls, and the final hammer blow was a horde of mandrills, who attacked while their approach was hidden by the permanent cloud of smoke and miasma at the front gates.

When Boatmurdered's final leader at last abandoned the smoke-filled fortress, only one dwarf child remained: Dodók Astlumash, sitting obliviously atop the dwarfs' forgotten treasure hoard.

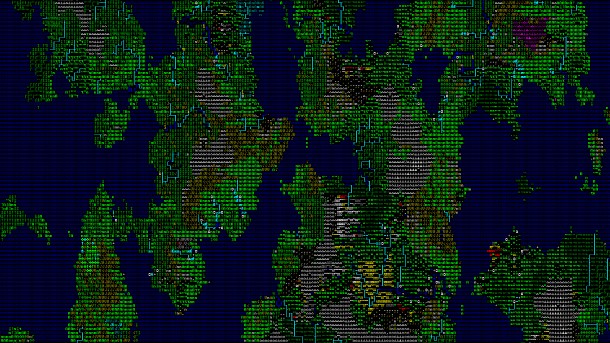

The ignominious (and frequently profane) history of Boatmurdered was carefully recorded and saved in the Let's Play archive, an offshoot of the old Something Awful forums. The colony was at least in theory a collaborative effort on the part of a group of forum mods, all playing a free game called Dwarf Fortress, which to the uninitiated looks like a mess of randomly colored ASCII characters. Each user acted as the settlement's supervisor for an in-game year, handing the save file off to the next player in line each spring. None of what happened was part of a traditionally scripted narrative, and yet the game still generated a remarkable string of stories. Dwarf Fortress uses carefully designed systems and simulations to foster "emergent storytelling," something that simulation games are uniquely good at doing.

Games are the only medium capable of truly generating stories as a function of interaction. While there will always be a place in gaming for traditional storytelling (think of the stirring stories of Uncharted, The Witcher 3, and Mass Effect), games that rely on emergent, player-driven narratives are doing something that books and film simply cannot. When you start a new game of the Sims, or Civilization, or Dwarf Fortress, nobody has written your next encounter or conversation. What happens next in your story is determined by the game's systems interacting with your decisions. Emergent stories don't necessarily center on the player, but rather on player choices, and they let you watch as your choices create cascading effects through the game's world.

The Story Generation Engine

Playing without a

crafted narrative usually means working with a certain amount of chaos. In the

case of Boatmurdered, "chaos" often came in the form of the native elephant

population, which collectively took an immediate dislike to the dwarfs. About

five years after Boatmurdered was founded, it had to be effectively locked down

due to constant elephant incursions. The dwarfs even named a few of the

creatures, which had become local legends for their dwarf-trampling abilities.

While the dwarfs cowered inside the fortress, the presence of the bloodthirsty elephants at the gates wound up being a blessing in disguise: A horde of goblins arrived to lay siege to the fortress, but they eventually wandered off when they realized the elephants had no intention of leaving the entrance. Meanwhile, craftsdwarfs (dwarfs also dislike the term "craftsmen" for obvious reasons) had begun fashioning great works of art at their workbenches, most of which depicted fellow dwarfs suffering violence at the tusks of angry pachyderms.

There are a couple things going on in Dwarf Fortress that make it a fascinating engine for creating original stories. The player has no direct control over the dwarfs; instead, they behave according to a specific set of rules, which include their needs, injuries, personal goals, experiences, and the environment around them. You can set out tasks and priorities for the fortress, but the dwarfs themselves will work out when they get around to actually complying with these directions, which gives the game a strong feeling of riding herd over an unruly and stubborn collection of actual people. The simple fact that each dwarf has a unique name goes a long way in helping the player establish subconscious, emotional bonds with the tiny, smiling ASCII characters.

Another important thing is that despite the simplistic graphics, the simulation happening under the Dwarf Fortress hood is complex enough to handle modeling dozens of individual dwarfs and their activities in their environment in convincing, if often infuriating, ways. As you watch your dwarfs putter about, you learn things about their behavior. Certain dwarfs are more attached to pets, for instance, and most dwarfs will risk life and limb for a chance to pillage the bodies of their fallen comrades. These game-driven personality quirks gradually coalesce into often surprising anecdotes within the story that emerges from a Dwarf Fortress settlement.

RimWorld hews closely to Dwarf Fortress in its game mechanics. It's a colony-building management game about survivors marooned on an alien planet. You'll guide your colonists as they build a base of operations, fight off wildlife and raiders, and develop relationships with each other in a hostile environment. But RimWorld takes the idea of story generation a step further by having players choose an "A.I. Storyteller" when they launch a new game. Cassandra Classic gradually increases the intensity of world events, such as raider attacks and droughts, while Randy Random can throw anything in the game's suite of events at players at any time. One enterprising modder has even added H.P. Lovecraft to RimWorld's roster of A.I. narrators, challenging colonists to stave off cosmic horror while trying to manage a settlement. Here again, the story is being written on the fly by the dynamics of player choices and game rules. A result of this is that it's easy to find yourself emotionally invested in the lives of your tiny stick figures. They seem real in a way that many high-fidelity game characters do not.

The emergent aspect of narratives in simulations works by designers assigning variables to important aspects of life and then letting these bounce off each other in game systems. This is an intuitive concept for anyone who's played a role playing game, but there are plenty of other settings where this approach works just as well as it does on a D&D character sheet or in a dwarf settlement. In sports, for instance, the important variables are all carefully identified and constantly updated by statisticians. This plus the fact that sports all involve games with explicit rulesets (think of them as "systems") makes them perfect for emergent narratives - just not the kind that normally involve dwarfs and elephants.

The Football Manager series of soccer-management sims lets players take control of practically any existing soccer club and staff it with whomever they wish. The games use current data on players, teams, and soccer mechanics to feed a highly sophisticated model, which produces results realistic enough that real-world soccer professionals (as well as sports bookmakers) use the dataset to inform their decisions, as Sports Interactive Studio director Miles Jacobsen discussed with editor Matthew Kato in a recent Sports Desk column. In game, the result is that players wind up creating their own alternate history of professional soccer: a story about the world of football, as it were. The fact that the simulation is so robust, and player decisions are so deeply reflected in the world, makes the stories of football season created by these games intensely personal, as HB Studios (makers of The Golf Club 2) producer Anthony Kyne wrote in a Game Informer Sports Desk guest column earlier this year.

Emergent Stories

Aren't Just For Simulation Games

Simulations lend themselves naturally to emergent storytelling because they

focus on game systems rather than a static script. But where does emergent

storytelling fit in a games landscape dominated by the more traditional

narratives of Uncharted, Dishonored, and Final Fantasy? It will certainly never

replace the crafted stories that have been part of human culture for thousands

of years, and even if that were possible, it wouldn't be desirable.

But aspects of the systems-focused emergent storytelling found in simulation games can exist side-by-side with traditional narratives found in bigger-budget "mainstream" games, and it's happening more and more. DICE recognized that the Battlefield series' main strength was the chaotic do-what-you-want multiplayer, and they designed missions for Battlefield 1 that can be completed with a variety of approaches, rather than by simply running from one shooting gallery to the next.

Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor used the clever "Nemesis System" to fill its world on the fly with believable enemies who remember you and compete with each other, even when you're not around. Thomas Was Alone and Volume creator Mike Bithell praised the game's innovation and encouraged others to follow its lead. "Somewhere along the way, we began designing games around the here and now," he wrote. "We forgot that games can also make rough simulations and gestures toward larger realities."

Fallout 4 has a traditional story, but it's also set in a complex (and often buggy) world that lets players bounce around off its various systems. There are players who abandon the main story altogether in favor of building astonishingly elaborate settlements in the irradiated Commonwealth wasteland.

As open worlds become more robust, it's practically a guarantee that we'll see more games embracing their natural capacity for emergent stories. Speaking to Le Monde in a recent interview, Ubisoft's Chief Creative Officer Serge Hascoet said the next Assassin's Creed game will take a step back from the series' traditional approach to storytelling and give players more free reign. Via Polygon:

"I don't want the player to go through a story created by someone," said Hascoet. "We have games like that still, but I ask more and more that we let the player write their own story - that they set themselves a long-term goal, identify the opportunities that are open to them and choose not to follow a path that was decided for them."

We'll always treasure and share traditional storytelling in our games, but they are also becoming more and more a way for us to create, experience, and share stories of our own. Simulation games are one approach to emergent storytelling, and they offer compelling lessons in narrative design for the medium at large.