Please support Game Informer. Print magazine subscriptions are less than $2 per issue

Casual-Gaming Pioneer Moves From Creative Treadmill To Hellevator

Some game developers seem to thrive on the spotlight, while others seem to prefer the space outside the glare. Adrian Woods is one of the latter types, though he's been instrumental in the creation of an entire gaming genre. Millions of people have played his Mystery Case Files games, but Woods, a game designer, is laid back and approachable about his success. "I've always shied away from the public eye," he says. "It's definitely something I could have taken better advantage of for my career and stuff, but it was just sort of like, 'Whatever, I'm just going to do what I can behind the scenes.'"

Woods left Big Fish Studios last year after finding himself in a creative rut. Now he and his new company, Fezziwig, are preparing to launch their first title, an escape-the-room game called Escape the Hellevator. The game may be grim, but Woods' personal story is an inspiring tale for anyone who's wanted to follow their passion.

He got into games while working at a marketing firm and ad agency near the Quad Cities in Iowa and Illinois. "I've always wanted to make games, so I started fiddling around with [Adobe] Director and playing with Lingo, and I started making little games,” Woods says. One of his first games was a word game called Chatterblox. It caught the attention of Paul Thelan, an entrepreneur who left Real Arcade to found a new studio. “I was shopping around [Chatterbox], and he caught wind of it and said, 'Hey, do you want to come work in Seattle?' I came to Big Fish when there were about 15 people; at one point, there were five- or six-hundred people all over the world. It was interesting to see that just explode. It was a lot of work, but it was neat to be a part of it.”

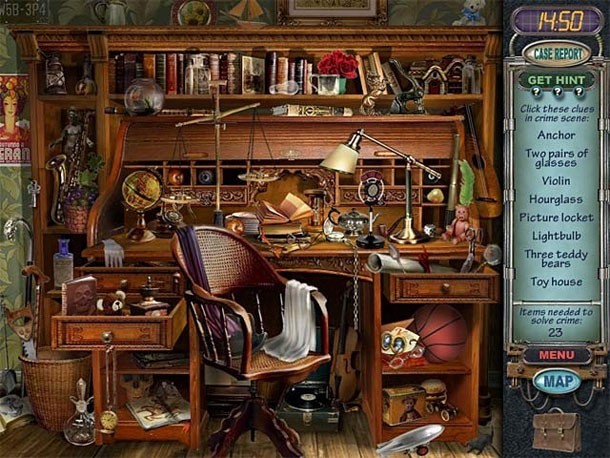

Woods started working on his first real project for Big Fish before moving northwest. It would become the Mystery Case Files series, which is considered to be the originator of the hidden-object genre. There have been 10 entries in the series since it debuted in 2005 on PC with Mystery Case Files: Huntsville, and Nintendo has republished four of them on the DS and Wii.

The term “hidden-object game” might not be as recognizable to hardcore players as, say, “first-person shooter” or “MOBA,” but the genre has been a juggernaut in the casual-gaming space for years. The games, which challenge players to locate items in visually complicated scenes, are easy to pick up and play, which has undoubtedly led to their popularity.

According to Woods, they existed in a primitive form through the I Spy games, particularly the PC game I Spy: Spooky Mansion. While the most basic building block was in place in Spooky Mansion – finding objects – it lacked the structure and storyline that Woods would add in Huntsville. “It was kind of my idea to put a mystery theme to it, because I didn't know what to do with this thing,” he recalls. “I didn't want to just say, 'Click and find an object.' It didn't seem like you had much of a reason to do that, so I decided to wrap it in a mystery. It was just a stupid little story.” Though Woods seems to downplay the importance of the story now, the addition seemed to work, and Mystery Case Files eventually became a phenomenon. At the time, however, he didn’t seem to know what he had on his hands.

Mystery Case Files: Huntsville introduced players to what would become a thriving genre

“The game came out, and I remember talking to my dad on the phone saying I wouldn't be in Seattle long because this game's terrible,” Woods says. “A few months later, it just absolutely exploded. The initial title of the game was CSI: Huntsville. It was basically a takeoff of the television show, and we got into a little bit of trouble for that. We started looking for a new name, and I suggested Mystery Case Files. Once that happened, we started making a few other games. Before we knew it, a lot of other people were coming in and starting to clone those games, which Paul didn't take too kindly to. After a while, he came around to it – ‘Hey, we can publish these games that other people are making.’ They had a lot of companies over in Russia and Ukraine that were cranking these things out, and Big Fish was publishing them. You got to the point where Big Fish would just say, ‘Hey, here's $100,000, make a game and send it to us when it's done.’ They've put out one of those every day for years and years now, so it's been extremely lucrative for the company.”

Big Fish continued to develop its own games and publish other casual- and hidden-object games. In 2012, the company purchased Self Aware Games, which was the top developer of mobile and social-media based casino games. Woods says he was already in a creative rut, and the prospects of moving to another seemingly less creative outlet didn’t excite him. “At that point I was so burnt out on making hidden-object games that I was like, ‘I don't want to make slot-machine games.’ ... I got burned out pretty hardcore and just said, ‘Forget it.’” He left Big Fish in 2013.

His inherent love of games never changed, though. Woods had been playing “escape the room” games, a genre that includes Can You Escape 3D, and the Zero Escape and The Room series, while getting back up to speed on programming. “I always wanted to learn 3D, and when I fired up Unity it was like a reawakening a little bit, where I was like, ‘I've got to learn this stuff, it's pretty neat what you can do with this.' That's kind of what drove me to leave what I was doing and then start up a little game of my own.”

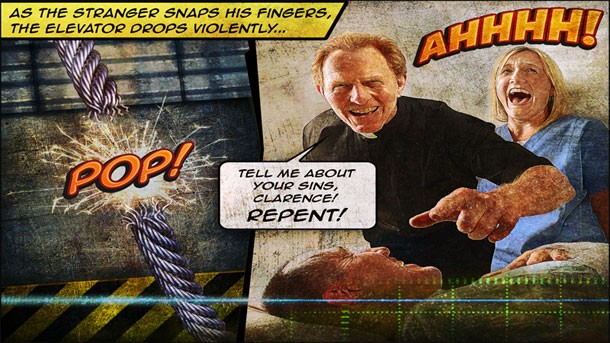

Each floor in Escape the Hellevator represents a sin committed by the reprehensible protagonist, Clarence Ridgeway

Over the next nine months, he taught himself Unity, and, working with Moksha Marquardt, an artist he worked with on the Mystery Case Files games, he created Escape the Hellevator, a mobile game that’s set for a release in the coming weeks. I played the first few levels of the game, and it’s a great little game that should engage people who are new to the genre or who have been escaping rooms for years now.

You play as a dying man named Clarence Ridgeway as he’s being taken down to the hospital ER on a gurney. He’s met by a priest, who performs last rites and urges penitence. Each of the game’s levels plays like a nightmarish version of “This is Your Life,” with players recreating macabre moments in Ridgeway’s past. Judging from the character’s propensity for embezzlement, arson, and worse, sending Ridgeway down the Hellevator shaft could be a completely appropriate punishment.

At the start of most levels, the Hellevator doors slide open and players are shoved into a small room, which represents a pivotal scene in Ridgeway’s life. From there, players will have to recreate some of his most evil moments to call the elevator car to the next vignette. The opening level, which serves as the tutorial, starts right after Ridgeway’s encounter with the priest. The elevator’s cable has snapped, and the car is skidding down the shaft. Your job is to release the emergency brake. Unfortunately, it’s behind a locked mechanism.

After a quick rundown of the basic controls – which are simple swipes, taps, and pinch gestures – the game is on. A scalpel rests on a nearby piece of medical equipment, and using the blade on a pillow reveals an object: a screwdriver’s handle. The rest of the tool is on the floor in the corner and, after assembling the components, I’m able to unscrew the panel to the brake controls. It’s not just a matter of pulling the handle though. Three shapes are above the handle, but tapping them into the correct sequence frees it from its housing. After a good yank, the Hellevator screeches to a stop. Unfortunately for Ridgeway, his journey is only beginning.

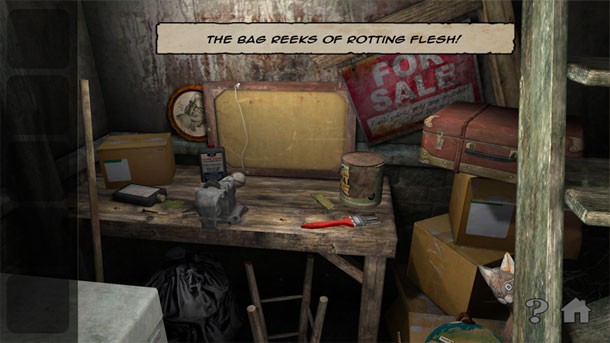

See that coffee cup? It belongs to your grandmother, and you'll need to poison it to escape this floor

The next level is more involved, and certainly much darker. Here, you have to find a way to poison your grandmother’s coffee – I told you it got worse. Her drink is on a kitchen table, and you have to scour the small room for the deadly ingredients. The environments are small, but well detailed, from the tacky wallpaper to the newspaper clippings and other items in the world. That’s important, because you’ll need to look carefully at the area and examine objects in your inventory to solve the puzzles. Considering Woods’ experience with hidden-object games, you might assume that he’d rely on a lot of pixel-hunting gameplay. That’s actually not the case. Objects are certainly placed out of sight, but it’s not a case of trying to squint to find needles in haystacks – something that would be a deal-breaker on mobile devices.

I won’t run through the steps I took to poison granny, but they did follow a clever and skewed kind of logic. It is an escape the room game, so there are those “screwdriver in a pillowcase” moments, but the majority of the challenges I faced were tricky without being needlessly obscure. There’s a divine punishment in the game’s story, but I’m glad Woods didn’t decide to flog players along with Ridgeway.

Woods isn’t saying what he and his studio, Fezziwig, will do next, but his excitement and enthusiasm for the future is apparent. “In a way it was kind of cathartic, because I could get away from that hidden-object grind, or that groove that I was in, and push myself a little bit,” he says. His success at Big Fish has given him the opportunity to break free and pursue his own dreams.

“If you're a creative guy, you have to roll your own and hope for the best,” he says.