Please support Game Informer. Print magazine subscriptions are less than $2 per issue

A Place for the Unwilling

Something feels off about the city in A Place for the Unwilling, a narrative adventure game from the Madrid-based indie developer AlPixel Games. Black smoke spews from the chimneys of homes and factories, friendly faces hide secrets, and a sense of mysterious, unknown dread permeates the streets of this Dickensian city.

In A Place for the Unwilling, which is due out next year on PC and Mac, AlPixel crafts a Dickensian world with a visually striking style that begs you to explore its darkest corners all while the hands of a ticking clock remind you the end is nigh.

The intriguing mysteries of the city and darkly humorous tone draw you in, but it’s the Majora’s Mask-style ticking clock mechanic that spices up the game’s narrative-adventure tropes. It adds urgency to a genre that usually allows you to play at your own pace. Although you can guide your character around the city, which is viewed from an isometric perspective, talk with NPCs, and add information to your journal and inventory, the clock is always ticking, except during conversations. The mechanic also makes choices that often seem insignificant – who to talk to, what area to explore – much more important.

“We asked ourselves if there was any way to make every moment meaningful,” says game designer Luis Díaz. “We came up with a solution. What if just choosing to visit a certain place or talking to a certain character affected your story? What if every second you're playing you're opening some doors and closing others?”

Players arrive in what is simply and mysteriously named “the city” as a newcomer, a young man who is taking over the trading business of his childhood friend Henry Allen who recently committed suicide. Over the course of the next 21 in-game days, each of which currently lasts around 20 real-time minutes, players explore their environment, learn about the setting, and form relationships with characters during the dying days of the city.

Every interaction matters. Deciding whether to spend the day talking with people, earning money through the trading system, or reading the daily news all becomes important to the narrative. Even staying out late at night can affect a playthrough.

“At night, the protagonist will start feeling tired. They can stay up late, though they’ll wake up later the next morning, which might mean missing some important events,” Díaz says.

With a lot of activities to do, it might seem like A Place for the Unwilling is a time-management game, and to a certain extent it is. However, the focus remains squarely on the city and the relationships you form within the city.

The setting in A Place for the Unwilling immediately establishes an intriguing blend of charm and dread. This strange combination runs through every aspect AlPixel’s adventure, from the art design and music to the writing and world building.

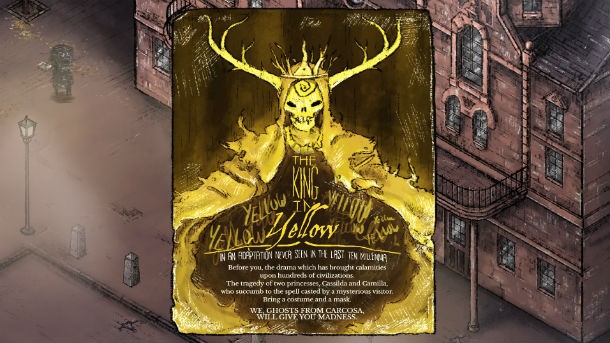

According to the team, the mood and atmosphere comes right out of their smorgasbord of influences, which are as diverse as H.P. Lovecraft’s cosmic horror, the darkly humorous work of Charles Addams and Edward Gorey, and the Grimm’s Fairy Tales-like animated miniseries Over the Garden Wall.

“In [those] works, a candid and heartwarming facade hides something macabre within,” Rubén Calles, a 2D artist at AlPixel, says. “[It] was quite important to define the mood we wanted to convey.”

A Place for the Unwilling has a similar mix of humor and horror, which its heavily shadowed, cartoonish art style helps portray. The city’s smoke-spewing factories, foggy cobblestone streets, and Lovecraftian dread lend a darkness to the proceedings that the characters, with their charm and humor, balance out.

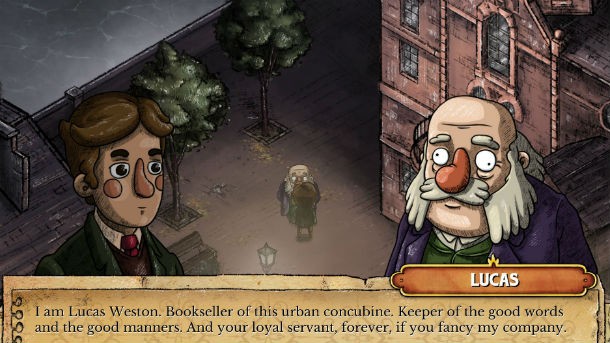

“Laboral abuse, police brutality, child slave labor, or political corruption are among the themes we’ll be addressing,” says AlPixel narrative director Ángel Luis Sucasas. “But, at the same time, we have a lighthouse-keeper that turns on and off the lighthouse whenever he feels like reading, a stuttering bookseller that can only express with clarity through singing, and a young thirteen-year-old anarchist who always carries a cigarette in his mouth. Both humor and harshness go along in our game.”

It’s especially important to have engaging and entertaining characters, considering that most of the time players spend in the game involves dialogue choices and conversation. A Place for the Unwilling is primarily about the relationships players form with these characters, which is why AlPixel took a different approach to its NPC population.

“Since our whole project is based on narrative, we decided characters would only mean something in terms of gameplay once they mean something to the story the player is building,” Sucasas says. “So everybody starts out as a shadow, they’re blurry strangers you can ask for directions but you’ll forget their faces soon enough. Once you’re involved with them in [a meaningful way], the shadow will fade away and you’ll recognize their faces as they wander the streets.”

It's a clever commentary on the way people inhabit and interact with real-world cities, and the effect of this design choice is disconcerting in a good way. Walking around the streets of the city past shadowy, unknown figures adds to the dark, mysterious atmosphere and as an outsider, it makes sense that the city would seem hostile or foreign to the player.

Just like how the ticking-clock mechanic spices up decision-making, this mechanic makes social interactions refreshing and meaningful. Not only are you engaging with someone who can help you out, you are bringing a friendly face and a bit of life to your world.

With its blend of humor and dread, an intriguing setting, and the pressure of working within a time limit, mystery remains at the heart of A Place for the Unwilling, and AlPixel is intent on surprising players at every turn.

“We want to disconcert players, make them laugh, horrify them and move them; never knowing which emotion will come up once they draw the next card from the deck,” Sucasas says.