Top Of The Table – The Pathfinder Playtest Interview

The Pathfinder Roleplaying Game has a fascinating history. Here is an entire system that arose out of the embers of the revised third edition of Dungeons & Dragons. As Wizards of the Coast took D&D in new directions with the fourth edition of the game, Paizo’s Pathfinder offered an alternative – an ongoing way for players to stay closer to the more familiar and beloved system they had played for years, but with some clever new twists. Sometimes informally dubbed by its fans as D&D 3.75 upon its official release in 2009, Pathfinder grew to compete against the very game it had diverged from, and to this day, many role-playing enthusiasts swear by Pathfinder’s rich campaign setting, strong rules, and dynamic play at the table.

Cut to 2018, and Wizards of the Coast has in the years since rolled out the popular 5th edition of Dungeons & Dragons, and Pathfinder is a system with nearly a decade of new content, rules additions, and other baggage to bear. By the admission of Paizo’s own director of game design, it’s time for Pathfinder to move forward on to a new edition – one informed by years of experience with the existing system, as well as the desires of an enthusiastic ongoing fan base.

I talked with Jason Bulmahn, director of game design at Paizo, and team lead on Pathfinder, and asked him about this new forthcoming edition of the game. Like back in 2008, the team considers its players’ feedback as integral to getting things right, so the first step into this new edition is a dedicated Pathfinder Playtest book release, coming this August. Within the Playtest book, players and GMs will be able to see what Paizo has been up to, with innovations and new rules to keep high adventure as the centerpiece, side-by-side with returning core systems that have been tweaked to keep all players – new and experienced alike – having a great time. And those same fans will then have the chance to offer feedback about those rules that will help shape the final release of the new edition.

As we conversed, Bulmahn shared insights into the new magic system, the move from character races to ancestries, and even shared some exclusive new sketches of the art on the way in the Playtest book. As a big fan of learning about new role-playing systems myself, I’ve chosen to run the bulk of our lengthy interview below, so Pathfinder fans can get the full picture of what Bulmahn chose to share. Enjoy!

Miller: When considering a new edition for Pathfinder, what were the design tenets you started with? What did you prioritize? What was the list you came to on a top level for what you wanted the new edition to do and be?

Bulmahn: In reality, the new edition of Pathfinder started the first day after we sent the first edition to the printer, because a game like this is such a big thing, and it has so many moving parts. Role-playing games have hundreds of pages, dozens of roles, lots of sub systems, and Pathfinder was born out of the 3.5 version of Dungeon & Dragons. As such, we inherited a lot of pieces of the game that, even when we started, were eight years old, and now 10 years after that we’re looking at parts of a mechanical system that are 10 years out of date. Well, I guess out-of-date might be the wrong term. The tech for it is almost 20 years old, and game design has moved a lot since then. I would say the start for Pathfinder: Second Edition really started almost right away with us understanding that there were some limitations to what we could and couldn’t do with the game.

The engine itself is great. It allows us to tell us these great, heroic stories while building the characters you want to build. We knew we wanted to keep that, but there was a lot about the way the math worked and how there were some elements of choice and the way you built your characters that wasn’t very friendly to new players. Even more problematic, at the higher levels of play when the story’s really coming together and you’re getting to the endgame, there are some math problems that make the game have some uneven play experience. You end up with some situations where high-level characters actually get worse at things when they go up in level, which is kind of odd and counterintuitive. We wanted to make the game a bit more true to the stories we wanted to tell.

I think in some way the engine wasn’t doing quite what we needed it to do, so the start for Pathfinder: Second Edition — or in this case the Pathfinder playtest which is coming out first — is that. We wanted to re-engineer the game to allow the game to emulate the stories we wanted to tell even more so than they did in the past. I think that’s where we started. We always try to start from a place of what’s best for the story, what’s best for the group, and what’s best for the players. All of our decisions spring from that. The most important part of the game is the people playing it and the stories they tell together.

Miller: You brought up the interesting thought that game design has come a long way in the last decade. What are some of the trends you’ve seen?

Bulmahn: I think a lot of people think of pen-and-paper role-playing games, and they think it’s like it always has been. It doesn’t really change; you sit at the table, you roll some funny-shaped dice, and you tell stories. In truth, over the past 10 years — even going back further than that — the game as a genre of entertainment has really made leaps and bounds in mechanics and storytelling, diversity, and with acceptance, and the audience has grown. There’s a lot of things changing. I would say in the last 10 years we’ve seen a big shift towards games that are a bit easier to understand, that are easier to get into. I think that’s become important to a lot of gamers, especially as segments of the audience have either grown older, or we get new segments of the audience that just don’t have the time I had when I was a kid. I didn’t have video games, I just had my books with D&D and I could spend an entire day just poring through a book trying to get all the details and get all of the rules in my head. Today, everyone has to compete with movies and cellphones and apps and video games, so I think having a game that’s a bit easier to get into, that’s a bit easier to understand, has grown more and more important over time.

I think the trick for us in particular is we need to push for that expression: A game that’s easier for people to learn, but we don’t want to sacrifice any of the depth, any of the richness. I want a game that’s easy for you to pick up and understand but still has the depth of options for you to explore and create the character you want to create. I think the industry as a whole has moved toward that in some directions — some games have moved that way, some games haven’t. Everybody’s trying to find their niche. I think the one we’re trying to aim for is one that has infinite diversity of choice without so much complexity that it’s really hard for you to understand.

I think that was part of the problem with our previous edition of the game. There was that real barrier to entry for new players, and that’s a term we use around here a lot. How much do you have to learn before you can start having fun? I think video games, above all else, have taught us that the faster the player is having fun the better off your game is. If you have to spend a great deal of time creating a character or reading a manual, that’s a time investment that you have to sink in before the fun can begin. I want to get out of the way and let people have fun as quickly as possible. With a pen-and-paper role-playing game, there’s obviously some things you have to learn and some things you have to do, but I want to minimize that by explaining some base concepts to you to get you going as quickly as possible.

I always think back to a game like Skyrim. They wanted to get away from the create-a-character screen and instead jump straight into a narrative where you’re playing (and they ask) what’s your name, and you type it in as the game is talking to you. We’re not exactly doing that, but we are looking at that as a model of how we can engage people from the moment they open up the book.

It’s beyond mechanics, too. I think narratively speaking we’ve learned a lot over the past decade. I think there’s a lot of games out there that are doing interesting things with narrative play and narrative construction and how they’re putting together their stories. It isn’t “here’s a dungeon map, open up a room, kill the monster, and take its stuff.” We’re trying to get more nuance, we’re trying to get a more emotional journey, we’re trying to build stories that take you places and let you explore aspects of not just your character, but issues that are important to you, issues that are important to the story and reach a depth you might not normally get.

I think it’s important we create games that speak to our more modern audience and we are working and trying our best to make a game that has a spot at the table for everybody. This new version of the game allows us to take even more steps in the right direction. We’ve always been a very diversity-friendly company, we’ve always been a forward-step-looking company, and I think the new edition allows us to bring even more of that into the fold in ways where everybody can have a place at the table, everybody can see themselves in the game. That’s really important to us.

Next Page: What makes this a new game, and not just an expansion to the existing rules?

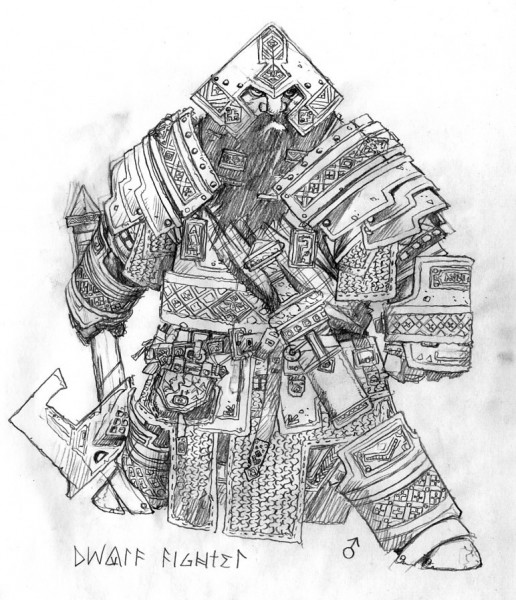

The Pathfinder Playtest will exlusively feature sketch art by Wayne Reynolds, like this new take on dwarves

Miller: What are some of the specific features that set this playtest of the new edition apart from the original game, and not just an expansion for the existing system?

Bulmahn: I think there are some things that are going to be really obvious the moment you pick up the Pathfinder playtest. If you’re familiar with Pathfinder and you open up that book, you’re going to see some things that are new to you. You’re going to see a new class that’s part of the core group: The alchemist has graduated to be part of the core offerings of classes, allowing you to mix bombs and drink mutagens and turn into a feral madman if you want, or whip bombs around the battlefield to blow things up. We added that because it’s such a good archetype of the fantasy genre that we’re interested in. In addition to ancestries, we have dwarves and elves and halflings and gnomes, but we’ve added goblin as one of our playable ancestries from day one. This is really important to us. Goblins have been a part of the Pathfinder schtick since day one, and making them a part of the game in a way that a player can experience the fun and mayhem of being a goblin is important to us, so we’re going to play with that and see how it goes. I think those are some of the obvious things.

The way some of the classes are put together is a little different, but ultimately a lot of this stuff is going to be very familiar, and that’s what we want. We want you to see the new, but we want you to understand the game at its heart is still the same. You still pick an ancestry, you pick a class, you pick feats, you pick skills. You are building the character you want to play. You create a vision of the character and you can put that character together using rules provided. Because of that, no two characters are identical. Every character, even if they’re all the same class or they’re all the same ancestry, they’re all going to be different. They’re all going to have choices and a unique expression. That’s the middle ground.

Once you start playing the game, you realize we changed some things about the engine to make the game itself play smoother. One of the big things that we had is when it came to your turn in-game. Say you’re in the middle of a fight, and your band of heroes are taking on a group of vicious trolls trying to rip you apart. When it gets to your turn, all of a sudden instead of having this complex menu of actions, the game master looks at you and says: “all right, you have three actions. What do you want to do with your three actions?” It’s really straightforward, it’s much simpler just on the play experience. Turns go faster, everybody has a better understanding of what they can and can’t do during that turn. You can take those three actions: you can draw your sword, you can move them up to your stride speed, and you can make an attack, and that’s your whole turn. Or if you start next to a bad guy with a weapon in your hand, you can just attack him three times because you have three actions — and that attack is one action. A lot of that stuff just makes the game run smoother.

All of the characters themselves have special actions and combos that they can take. The fighter has sudden charge, where he can spend two actions and move a whole bunch and attack just for two actions, which is better than what he could normally do. The spellcasters can spend actions to cast spells. All of it plays together in a way that everybody can understand what everyone else is doing, which helps everyone understand and have a better picture of what the environment is. That comes back to our core tenets that we want everyone to be able to fully understand the environments and the story as it unfolds in front of them. I think before we got lost behind determining if something was a move action or an immediate action. Where was that? It was a little fiddly for what we needed it to be. We need it to be a straighter expression, but this still allows us to have the broad variety of things a player can do. We can change how actions fit together and how pieces work. We can still tell the same stories, it’s just easier to for everybody to understand.

Miller: In what ways does this new edition speak to someone who has never played a role-playing game before?

Bulmahn: I think with the Pathfinder playtest, we’re taking the first steps toward what will be a game that is really open and inviting to new players. I don't’ think we’re quite there yet. I think that’s part of the process that we’re going to refine through the playtest, but the initial goal is this: we want you to open up the book and there’s an introduction. It covers the base concepts of play, tells you about what a character is, what a game master is, what choices you need to make. It gives you an outline of the things you need to do to make your character. It starts with things like: let’s not worry about the roles yet. Just imagine what you want your character to be. That’s where we have to start. We want to start with that picture. We don’t want to start with rules, content, and feat choices. We want to start with the dreaming up of what you are going to be playing. What’s the persona you’re going to be? And then we walk you through step-by-step, carefully taking you through as you make the choices to make that vision a reality.

I think in our previous edition we had a little bit of trouble with that kind of narrative description of how you build a character, but this gives us a brand new chance to approach that fresh and understand that a lot of people are coming to Pathfinder as their first role-playing experience. We need to make sure we do the things that are right by them, teach them how the game works, here’s how your character is created, and here’s how you play that character at the table and bring them to life. If we can walk you through that process, there’s a better chance that you’re going to be invested in the story, and you’re going to care about what happens to your character because it really feels like your character. You feel like it’s something you made; you’ll craft it from the rules that we gave you. That’s really important to us, giving you that investment in your character and the story that they are experiencing. I think for the new player, the playtest document is going to be the first step toward walking through how this process works, and then through the playtest of that book, we’ll learn more about the process and make it even better for the final version of the game. But yeah, it’s a lot of diagrams and charts and a lot of page references telling you where you need to go and explaining to you what it is that you’re looking at when you need to make the right decisions.

Miller: The product we’re talking about today is, as you say, a playtest. It’s not a final, new edition of Pathfinder. As a designer, what are most important, outstanding questions that you’re hoping to answer with the playtest?

Bulmahn: There’s a bunch of math buried in every game. The Pathfinder is no exception to that. There’s math in how the game works behind the scenes, and the moment we wanted to pull out and replace that math with better math, we realized we’re tinkering with some fundamental forces.

If I could explain it you narratively, you start out as the son of a blacksmith, and you worked in your dad’s smithy until orcs came and burned it down, and you had to go on the road and become an adventurer. When you’re the low-level adventurer and you just picked up your dad’s sword and you’re going out on an adventure, you expect to be living by the skin of your teeth. You’re not very good at killing orcs yet, you need to roll well to hit, and life is chaotic and random and you might not make it because you’re low-level and life is dangerous. But as you increase your level you become more sure of yourself. You start being better at fighting, and you’re wearing better armor and you become a legend and people start talking about you and your exploits. That’s part of the classic hero’s journey.

Even beyond that, that’s a narrative that a lot of people understand and they expect that as they become more powerful, they become more sure of themselves. Things that they want to do become more likely to happen. To be honest, that all translates back to a bunch of math formulas that say, as you go up, certain assumptions change about how you take your turn and how the game works. For the playtest, we’re going to be testing a lot of these functions, but we’re not going to be that blatant about it.

At the same, we have a playtest adventure that is going to be released at the same time, and also have it available for free as a PDF. In that adventure, there are seven short adventure stories that should take you one or two sessions to play, each of which explores one topic in particular. I don’t want to spoil any of them because we don’t want to taint any playtest results, so we’re keeping it close to the chest on what they’re about, but it shouldn’t come as any surprise to say that we’re going to be testing various parts of combat to make sure some of the assumptions about how the numbers work and how all of the games feel is in the right place.

We’re going to be pushing boundaries in some cases. We’re going to try things like, this is an adventure with a lot of encounters, and this one’s a series of long, easy encounters. We want to make sure that everyone has the right feel from the game, that they walk away going, “This felt right, this matched my expectation of what the story is.” The playtesting isn’t so much about how much damage you did on round 14. It’s more about, after an encounter, did you feel like that was hard? Was that a challenging encounter? How difficult was it for your group to overcome that challenge? Once we’ve got 50,000 people playing a game, we get a lot of good data really quickly. I think that’s our big push.

I think there’s a lot of little pushes, too, like asking players: “what did you think about this particular feat?” There’s a lot of specific questions we’ll be asking as well. There’s going to be a lot of surveys that go up online and very robust message boards that will be — in fact, already are — giving us a lot of feedback about the spoilers we’ve been releasing. The playtest is a chance for us to examine all the choices we’ve made, to make sure that we’re making the right ones for the game and for the community as a whole. We’re proud of the game we’ve made, but we understand we’re just one team of people trying to bring one vision to life. If the fans want something else, they’ll tell us, and we’re more than willing to adjust to make sure this game meets the expectations for as many people as possible.

Next Page: How will the campaign setting change with the new edition?

Here's a first glimpse of the hobgoblin appearance for the new edition

Miller: I want to ask you a little bit about the philosophy behind moving to a new edition. In its earliest days, Pathfinder was a way for some players to continue enjoying a style of play the enjoyed in D&D 3.5. A decade later, as you consider a new edition, is there a danger of splintering your community? What does this mean for your player base?

I think that thing that we really are trying to stress, and the thing that really was our goal from the beginning, was that we really are trying to keep the feel and the spirit of the game the same. We’re not trying to sub this out for a game you don’t recognize, that doesn’t work the way you think it does. On the whole, we have a game system that now is closing in on 20 years old. In that 20 years, for the past 10 of it, we’ve been working on it exclusively. There’s been a lot of innovations, and there’s been a lot of additions. Think about when we released the core rulebook back in 2009; archetypes weren’t a thing we had invented yet. The downtime rules weren’t a thing yet. There were just so many parts of the game that we hadn’t even come up with yet.

We added all of those things to Pathfinder, but by their very nature they were just add-ons. They weren’t seamless parts of the whole. They were built-on additions. Those work and they get the job done, but they never quite feel like they’re a native part of the game. They always feel like they were attached, and you have to make some adjustments and changes to make them work. The game certainly accommodates that, and there are certain parts of that that have been more successful than others. People love archetypes, and looking back at the game and the way that archetypes are attached to the game, there are things we don’t like and some things that we wish we could a little differently, and this gives us a chance to do that because it allows us to design the game with them in mind, which is something that we didn’t do the first time.

I think for those who are afraid that we’re losing our way or heading off in a direction they don’t agree with, I think once they get a chance to see most of the game they’ll understand that we really are trying to create the same experiences everyone knows and loves but with a game that works a little better. It’s not that we don’t love Pathfinder, by no means. We love the original game. I spent a decade of my life working on it, but it’s time for us to give the whole system a tune-up, and in some cases realize there’s a few parts that probably need be replaced.

Our community is amazing. They have gone with us on this journey for the past 10 years, and I have faith that they will come along with us to the playtest, and they will tell us what they like and what they don’t like. They’ve never been afraid to that in the past, and I don’t expect that to change now, which means we have a chance to adjust and make this the game that we all want to see. I think we’re close. To be totally fair, there are some things that have people concerned right now. There are some elements of the game that people aren’t sure about. They haven’t seen all the rules yet because, honestly, we’re not ready to reveal them yet. The game is still being laid out. It’s not even done. I think as we get closer people will start to realize that they tend to tell the exact same stories. One of the first things that we did with this is converted a first-edition module literally on the fly. I did it with no notes for the folks at the Glass Cannon podcast and ran the game for them without notes. That’s how easy it was to convert, that’s how close it is narratively and structure-wise. They were able to play the new characters and the new game and it was great.

There’s always apprehension whenever there’s change, and we understand that. We’re afraid of change, too, right? I’m never comfortable when a thing that I love is going through a renovation, but I oftentimes realize that it's for the best. You look backward and think those were things that needed some work. They may not agree with the directions we’ve taken, and that’s of course a danger, but we’re going to do our best to make sure this is a game that everyone can enjoy.

Miller: The Pathfinder game also includes a dedicated campaign setting that you’ve been fleshing out over the years. How does this new playtest move the fiction forward?

Bulmahn: I don’t want to spoil too much because I know there are people a few rooms over from me that will run over and throttle me if I told secrets, but I can say that we will be advancing the timeline of our world, which has always technically been advancing, which started out at 4707 in 2007, and every year after that we’ve kind of unofficially advanced the timeline, so the adventures we published in 2008 took place in 4708. When we start releasing new material with the next addition, we will jump the timeline forward fully to 4718 or 4719. And there will be some changes to the lore to go along with that. Some of the plot lines from the first edition will be resolved and baked into the storyline of the game, but I don’t think you’re going to see anything huge. We’re not blowing up continents or changing the world in ways that will be unrecognizable. We’re not killing off half of the characters or anything drastic, but we are going to be bringing a lot of new interesting storylines to the front. First Edition had the world of Golarion, and it had a lot of varied and interesting places. For those who aren’t familiar, Golarion is a world that kind of takes our philosophy of storytelling and makes it into a world. If you want to tell a horror adventure, there’s an entire nation that’s gloomy and filled with vampires and wolves. But if you want to tell a story about oceans, sailing, and Vikings, then we have a nation for that, too. If you want to go down to a desert with pyramids, we’ve got a place for that as well. We looked at all the story types and asked, “What types of stories do people want to tell? Let’s put a place for them.”

With the new edition of the game, that doesn’t really change, but it does allow us to take some things that we’ve been sitting on and thinking about for a decade and start playing around with them. The playtest adventure is the culmination of 10 years worth of storytelling wrapped into one, giant adventure. But there’s some other things happening with our adventure paths, especially in the lead-up to our new edition that I think people are going to find really exciting, starting with this year’s Gen Con. We’re releasing Return of the Runelords; for those who aren’t familiar, the very first adventure path we released was called Rise of the Runelords. There might be some interesting through-line stories floating around in there.

Miller: The industry has seen a huge upswing with player engagement from live streaming and recording of role-playing sessions. Are there ways you’re hoping for Pathfinder to further tap into that phenomenon?

Bulmahn: As a company, we’re starting to embrace that direction more. We’ve seen the change happening in the past few years with the rise of Twitch and various podcasts and broadcasts of role-playing games that have become very popular. I’ve watched a lot of them myself and they’re great. A lot of fun. For us, one of the things we looked at was, “What aspects of our game make it difficult to be shown in that sort of environment?” To be honest, the answer for what makes Pathfinder difficult to stream is similar to the answer of what makes Pathfinder difficult to learn and play. Because the game is very technical and has a lot of exception-based mechanics, that bogs down the play of the table and makes streaming seem slow and meandering, whereas a system that just says, “All right, it’s your turn. You have three actions, go,” is much quicker and flows better.

We’ve made adjustments for that, but I don’t think we’ve made them specifically so Pathfinder plays better on Twitch. But it’s a result of us trying to make the game simpler to understand and easier to play, which makes for a game that plays better in those sort of environments. When it comes time for us to do the Playtest, you’re going to see us do some Twitch streaming. I know that we’re constantly doing podcasts, and there are a number of folks in the office who are involved in various liveplay games that are streamed or captured for YouTube. We now have a dedicated Twitch studio in our office, so we’re in the process of getting all the tech set up, so when it’s time to show parts of the game, we can do that. We can show you how we play, which is fun! I really enjoy playing games for audiences and showing off how we roll, as it were. That’s a cheap joke. I’m sorry.

We’re excited to do that. It certainly seems like the desire to see people play role-playing games has increased dramatically. You don’t have to look very far on the Twitch channels to find huge liveplay numbers, so that’s what we’re looking to do.

Miller: As a longtime RPG player, it’s been wild to see this sudden celebrity culture around streaming and playing game – it’s something I would have never imagined when I was playing as a kid.

Bulmahn: I got the first hint of it a few years back when I was a guest at Dragon Con in Atlanta and they asked if I could run a celebrity game for some of the other guests at the show. I sit down to play with Jim Butcher of Dresden Files fame, and Richard Garriott of Ultima – literally Lord British. I’m sitting here running a game for them and voice actress Monica Rial, and Ian Frazier who helped design Mass Effect Andromeda, and I’m running a game for them in a room with 500 people who are just excited to see us role-play. It was surreal and truly amazing. It’s ridiculous to me how much people love that sort of entertainment and I thought I’d never see the day that people want to watch other people role-play, but if you get a bunch of entertaining people who are really getting into character, it really is fun to watch. I think it’s all about finding people with the right engagement level and the excitement for it and you’re good to go.

Next Page: Exploring the new magic system for Pathfinder's second edition

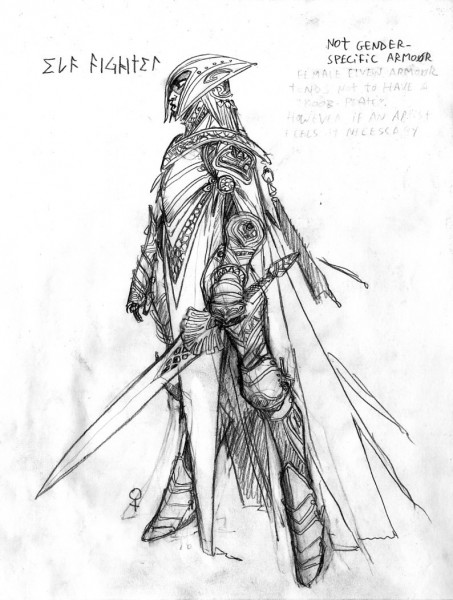

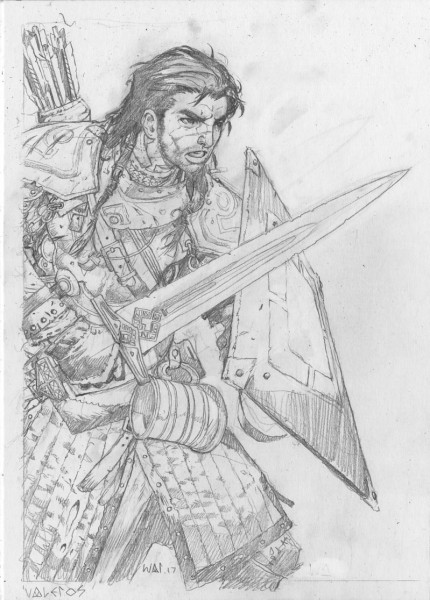

The gear and weaponry for different groups are being reimagined for the new edition

Miller: What can you tell me about the new magic system in the Playtest? What makes it distinct, and what aspects are you excited about?

Bulmahn: At its heart, like every system, it still works the way you’d expect. If you’re a spellcaster, you can prepare your spells every day so you know what spells you can cast and once they’re cast, they’re gone. We kept what is called Vancian spellcasting. There are still spontaneous spellcasters who don’t quite work that way but are close. They have spells that they know that they can cast from a certain amount of slots.

A lot of it is familiar, but when you look at the spells themselves, you’ll find a lot of changes. One change we’ve talked about publicly already is this concept of the four levels of success and failure. Whenever you get hit with most of the spells, they have four levels of effects that happen when spells are cast on you. You have to make a saving throw and you might critically succeed, succeed, fail, or critically fail. What happens depends on where you land on that chart.

If you critically succeed and make the target number by 10 or more, maybe nothing happens to you because you’re totally resilient to it. If you succeed, maybe something small happens or nothing at all. If you fail, something bad happens. If you critically fail, something terrible happens to you. Take the simple example of a fireball, which does 6d6 fire damage. It doesn’t scale. It’s a third-level spell that does 6d6. If you make that saving throw, you take half damage. If you critically make it, you take no damage. If you fail it you take full damage, but if you critically fail it you take double damage, which can be crippling in the middle of a fight. You can take 12d6 from a third-level spell, which is really bad! You don’t want to do that. But your odds of critically failing are small. But it can still happen with a more powerful spellcaster throwing it at low-level foes; the odds of critically failing go up, which means they’re probably going to get knocked out of the fight faster, but that’s appropriate because they’re low levels.

Some of this allows us to tell stories a little better, which goes back to our goals with the game. But what’s also interesting is that if you have spells that you love like fireball. You can prepare those in a higher-level slot, so let’s say you want to do more damage; you don’t want it to do just 6d6. You want it to be valuable to you when you’re fifteenth level, so you’re going to prepare it in a fifth-level spell slot instead of a third. Every spell slot you put it in that’s higher than third, you get an additional 2d6 damage. That’s what happens to fireball when you put it in a higher-level slot. There’s lots of spells in the game that do that. I think lightning bolt does more damage.

Other spells have multiple targets when you prepare them in higher-level slots. One spell can only affect one target when you prepare it as a third-level spell like Paralyze. But if you prepare it as a higher-level spell, you can affect multiple targets in an area and paralyze a bunch of people.

A lot of spells have this built-in spell scaling in them, whereas before we would’ve had to present three different types of spells that do the same thing, so in some cases, the game’s just easier to play now. You go, “I want to be the fire mage, so I’m going to prepare burning hands, fireball, and all sorts of stuff.” You can fill up all your slots with whatever you want your character to be. So, in some cases, it gives us flexibility to do different things with the magic in the game, and in other cases, it allows us to make the characters we want to make. We don’t have to worry about not having a good fifth-level fire spell so players won’t have anything to put there. You end up taking steps that don’t fit their stories, so we’re excited for the changes.

I’m also excited for the introduction of tenth-level spells. I know there are a lot of people that are like, “What’s the deal with that?” There’s a couple spells we’ve looked at from the game and went, “Wow, these are so powerful. I’m not even sure we want to allow those as ninth level.” We want to walk those away so you have to do something more to get them. You don’t get tenth-level spells automatically. You have to take a feat just to get them. That’s where spells like Wish live now. Let’s be honest, it’s one of those spells that can do anything. We have some guidelines built into the spell, but it really is there to be the make-or-unmake-reality spell. You shouldn’t use it to wreck your campaign, since it always comes with the chance that the DM will mess with you and corrupt your wish, so you have to be careful.

But this also gave us the opportunity to write other cool tenth-level spells. There’s one for druids that can wreck an entire environment by invoking a devastation on an area. Don’t make a high-level Druid angry because they will ruin your town! I think we’ve got another spell floating around there that allows you to turn into Godzilla or something akin to it. There are some crazy things floating around with the high-level spells of the game, but that’s appropriate for that level. At that point in time, characters are able to do amazing, almost god-like things when you’re up at the nineteenth-level or something. You know, the magic system is really exciting.

It’s going to be interesting to see how people respond to some of it. There are some things that are disappearing and others that got folded into other things because it was easier. We didn’t need cure light, moderate, and serious wounds as separate spells. We now have a heal spell that you can prepare in higher-level slots. It does the same thing but works better and is much cleaner to understand. You don’t have to look it up because you know what it does, so yeah. Magic has always been a great part of the game and something we wanted to make cleaner, so that it plays nicer with other characters. There’s always been a perception in the game that once spellcasters get to a high enough level, they don’t need anybody else because they have spells that can do everything in the game. We looked really hard at some of the spells that allow that and changed a lot of them to tamp back on some of that, so that the rogue doesn’t suddenly feel like there’s no reason for him to be on the adventure because everyone else can find traps and disarm them without him. We’ve taken a lot of steps in those directions to make spells play nice with everybody else.

Miller: I want to ask you about the art of Wayne Reynolds, who’s been inextricably tied to the Pathfinder aesthetic for a long time. Can you tell me how he’s involved with this playtest and the subsequent new edition?

Bulmahn: Wayne is an amazing artist that has been with us since the very beginning. He’s done the cover to every core Pathfinder book we’ve created and his work speaks for itself: it is the look of our game. We’ve always used Wayne and love him. His talent is second to none. When it came to the new edition, we obviously reached out to him and said, “We want you to be a big part of this.” Everything that he has ever touched for our game - any monster or character that he has designed has become a classic. The look of them is so uniquely his style and, because of that, so uniquely Pathfinder.

One of the things we did early on in the process – and this was last year – was we actually had him come to Seattle and hang out with us here in the office for three weeks. Over that time, we had him doing reams upon reams of sketches, iterating on various design ideas and concepts, looking at how some of the new monsters, creatures, and characters work in the game. He worked with us to kind of develop new looks for some things to refine and revise. For example, dwarves look more uniquely “dwarfy” to us. We widened the bridge of their noses, their brows are heavier, they’re a bit squatter now. We designed armor that made them look like a mountain range with their shoulder pads and helmets, right? One of the things I love is this evolution. For example, we’re known for our goblins, but when it came to orcs, their designs have been all over the place. We sat down with Wayne and redesigned orcs so that when people look at them, they’ll go, “Yep, that’s a Pathfinder orc.” He did some amazing work there.

Wayne has done incredible work across our line designing gear and weapons. One of my favorite things is that in designing halflings, he decided that their gear – because of the way they work since he knows how our game world works really well – needs to be multifunctional since they’re nomads and travelers by trade. So, he has their helmets that they can flip over and use as a stew pot. They have shields and the handle is foldable, which they can use as a fry pan. Their gear is weirdly functional and dual purpose, but still looks cool. Wayne also redesigned Elven gear, Dwarven gear, and other stuff people are familiar with in our game. The Playtest rulebook is going to be exclusively Wayne Reynolds art, most of which is going to be brand new sketches that happened from that three-week period and after. We may try and do that for the final rulebook as well.

Miller: Pathfinder has always featured several iconic characters that typified certain races and classes. Is the plan to bring back all of your iconic characters?

Bulmahn: For the most part. I think that the core eleven are coming back. I think we’re swapping out the alchemist for a goblin because that’s new and we don’t have a goblin iconic, so we have a goblin iconic alchemist. The other iconics are all coming back. Many of them have received some upgrades to their looks and costuming and, in some cases, their equipment. Valeros went from having long and short swords to a longsword and a shield. We made him a sword and board fighter. There’s a lot of fun, new things you can do with sword and shield. Some of them have modernized outfits created that don’t look the same way they would’ve looked ten years ago because sensibilities have changed and where we want to take some of the characters have changed. But their stories and backgrounds haven’t changed.

Miller: So, the expectation is that Reynolds is going to be involved in the visualizations of those new characters?

Bulmahn: He’s already done sketches of all of them, so we have his work. Each character class opens up with this amazing full-page piece of the iconic in action and it’s fantastic.

Next Page: Ancestries explained, and a closer look at archetypes

The goblin alchemist is a new iconic character in the Pathfinder universe

Miller: One of the terms you used earlier in our conversation is ancestries, which I understand to be a move away from race as a core concept in the game. What prompted that decision? What does it mean from a design perspective? Should somebody think about races being analogous with ancestries or are you changing things about the design concept as well?

Bulmahn: It’s a little bit of both. We changed the name because, to be honest, “race” didn’t mean what we wanted it to mean from a mechanical sense. And race as a term has some problematic meanings and overtones, coming with baggage about what it’s supposed to mean, right? The way we redesigned ancestry doesn’t really fit, so all members of an ancestry aren’t identical. They have very big differences and we wanted to move toward a term that allowed us to step away from any sort of scientific definition of species, race, or anything like that. We wanted to move to a term that’s free of a scientific definition because it allows us to do some things that we couldn’t otherwise do. What we’re saying is, “Where did you come from? Who are your parents?” They’re important questions, and they define part of who your character is.

In the future, it allows us to do things like, let’s say one of your parents was an angel, half-angel, or even quarter-angel. What does that mean? How can we build that as a character without necessarily having to provide this entirely separate write up or construction? Every ancestry gives you base abilities that all members of your ancestry share like your speed, languages, and a couple other things like that. But they’re not too in-depth on rules content, and each ancestry includes a series of ancestry feats you can choose from. You get one at first level, another at fifth level, and so on. These allow you to explore your ancestry and be a unique member of that group, culture, and setting. It allows you to say, “This is what this means to my character and that’s what’s important to me," instead of getting a package of abilities you have mixed feelings about that result in some you ignore for the rest of your character’s career.

We wanted that choice to be meaningful to you throughout your adventuring career, and we’ve seen this in other games too and how much more of an impact it has on your decisions. We also realized that in moving to ancestry, it opened up the avenue for us to kind of talk about it in a broader sense and say, “You are more than just those things. This can mean more and mean what you want it to mean based on your character.” So, if you want to say, “I was an elf, but I was raised among dwarves,” what does that mean? We’re building ways in the game for you to make these distinctions and possibly pick up some dwarf feats. We’re still trying to figure out how this will work during the playtest, but I think we’ve got a solution, so bear with us. It might take us a bit to get right. But you can have a character that crosses those lines that makes sense, which is fun and exciting. It’s the story of your character. The rules are opened up in a way that lets us tell even bigger stories.

Miller: Let me make sure I understand how that would function, to use your example of an elf raised by dwarves. Conceivably in character creation, it’s not fundamentally the genetic background of being an elf that would determine that character’s bonuses or special abilities, but instead that could come from their background of being raised by dwarves?

Bulmahn: What we’re trying to figure out is how to make that work mechanically without the player just picking whatever they want. We’re still playing around with that and I think we might have something that will go into the playtest, but we’re still teasing that out right now. That’s ultimately the goal. What I’d love to be able to do is to have a system in which you can say "I was an elf raised by dwarves and there are certain elven feats that I can take because they’re genetic. This is a thing that elves have based on being elves." But then there are other things that are cultural. For example, dwarves have a training and fighting against giants. There’s nothing genetic about that really; it’s more of a cultural thing. There’s nothing physiological that allows them to fight giants. It’s about the training regimen that they have that allows them to fight them after centuries of perfecting that. It kind of makes sense that you might be able to pick that up if you’re not a dwarf, but there are other things that don’t make as much sense. For example, elves have magic running through their blood, but it wouldn’t make sense for a human to pick up that ability because they don’t have magic running through their blood.

We’re trying to tease apart which parts of the ancestries we can keep exclusive to that ancestry against the ones that background and choices can dictate. That’s kind of where we’re heading. You might make a choice to say how you were raised in order to access certain things.

One of the other things you do during character creation is pick a background. When you’re building a character, you have to consider your ancestry, your background, and your class. Those are the three most important character choices. That background might be able to solve some of those problems. If you have a background that allows you to pick an ancestry feat that isn’t your own as long as it’s not illogical. That could be an interesting choice and is one of the avenues we’re exploring. It’s still coming together. That’s the trick about talking about a book before it’s hit the printer. We don’t 100% know what’s going to work or not, so this might be a dream that has to wait until we release later on in the playtest, but it’s something we’re shooting for.

Miller: Other than ancestries, one of the other terms you touched on, for people who aren’t familiar with Pathfinder, is archetypes, and taking something that came along later in the game’s life cycle and making it part of the core rules. Tell me about why archetypes are important, what they are, and what they bring to the core Pathfinder experience in this playtest.

Bulmahn: Archetypes in Pathfinder’s first edition were a way to expand on the ordinary class type, so instead of being a regular rogue, you could be a pirate rogue. Instead of rogue abilities, you could pick up some pirate abilities that speak to the way the rogue works and make sense for the rogue. The way they worked in first edition is that instead of getting uncanny dodge, you’d get an ability to swing from ropes and attack people on boats. You get some sort of bonuses when you’re climbing around in riggings and stuff like that. You could very easily build what were basically subclasses. It’s a rogue, but a slightly different version of that. We call those archetypes because we’re basically saying it’s something you choose and it becomes part of who you are. There are great ways to customize what you wanted to be.

The new version is built upon the idea of classes that have all these feats that they give you. When it comes to archetypes, it makes sense that they have additional feats you can choose. In the new game, they work similarly to how they did before, but instead of telling you what you’ll lose, you’ll get a package of feats you can choose instead of the feats from your class. They work just like an add-on package for you to choose from. It allows them to be more open and it’s not tied to specific features of classes. This kind of speaks to whatever character wants that to be a bigger part of their character concept. The rogue might want to be a pirate, but so might a wizard. It might have a feat or two that’s better at casting spells that burn sails or knocking holes in boats with lightning bolts. There could be a wide variety of abilities that speak to how the class works and you choose the ones that are appropriate to you. In this case, the archetypes allow us to expand the character types that we have. We’re not just at 12 classes, but we have dozens of different character concepts to explore from that decision alone, not to mention all the choices you have within skills and feats. It’s about giving you as many tools as possible to make the character you want to play as. Archetypes are a big tool that allow us to do that. They’re a box of toys that we can let people play with to customize their character. The playtest will have a number of archetypes in it, but we’re not putting them into the final version until we have time to test it out.

Next Page: Learn what Pathfinder's designer is most excited about in the new edition

Existing iconic characters like Valeros are having their appearances revised for the new edition

Miller: To reframe what you were just saying, archetypes aren’t tied to a specific class or ancestry, but they’re their own entity that can connect to any number of classes?

Bulmahn: Here’s the great thing about that. With the way we redesigned them, they can connect to a specific class, but they don’t have to. We can design an archetype that speaks directly to what sorcerers are supposed to be and exclusive to them, but for something like ‘pirate’, there’s nothing that says that anyone can’t decide to be part-pirate. That’s a concept that you can apply to almost any character. It doesn’t make sense to recreate the archetype for each class when we can create a suite of feats that speak to what the pirate is, and then pick the ones that you want as needed.

Miller: It sounds like your character system is even more reliant than it once was on feats that are coming from a lot of different places. Is that a fair assumption?

Bulmahn: It is, but I think it’s important to understand that they were in the previous version of the game, but we called them different things based on the class. So, you had barbarian rage powers and rogue talents and monk ki abilities. Everyone had their own unique thing, but it never made sense to call them talents based on their class. In reality, they’re both trying to speak towards certain skills that you pick. What we’re trying to do is step back and say that a feat as a concept is that you get to make a choice. Instead of reinventing a new name and explaining it differently, maybe we should just standardize it. If you pick a new class, you now immediately know how to build a character because you already know how to pick feats. You don’t have to think about how rogue talents work or how arcanists' discoveries work. They’re different, but not really. They were different only in how they advanced. Some of that was a distinction, but not a difference. We’re trying to move away from some of that and see what kind of realm that allows us to explore. So far, it’s made it so much easier for players to move between classes. The things they have to learn are the choices they want to make, not how to make those choices.

Miller: That is often a challenge for when a new player comes in for any game. They might start with a fighter, and find out how all of that works, then they start a cleric on the next campaign and it’s a whole new ballgame.

Bulmahn: That goes back to the concept that we only want to teach you how to build a character once. This is how characters are built and how they advance. I teach you that once and then can do it again with each character. It gives the player more freedom to choose different classes without too much trouble. You just need to learn about the individual choices to be made, which is part of the fun anyway. The fun part isn’t learning how rogue talents are distributed, but learning what they can do. Instead, we just changed them all to feats and allow you to choose between the feats that are available. We understand that it seems a bit confusing for a terminology standpoint, but once you see the master chart, it becomes really intuitive. Then you get to continue onward with the story and the concept of your character in a way that feels organic and straightforward. You can just make the decisions and move forward.

Miller: As its designer, you’ve played this game for a lot of years. What are you most excited to experience in the new edition?

Bulmahn: One of the things I’m most excited about is being behind the screen. I love running the game, I love telling my own stories and crafting the player experience. One of the things that has me the most excited is how we’ve approached monsters. We’re in the process of creating new ways to build encounters. You’ll still build encounters that you want to build and tell stories you want to tell. Ogres are still low-level monsters, dragons are powerful. But it’s really exciting to see the monsters behave differently. After 20 years of playing with the same monsters, it can get a little predictable. The moment something like a bear with the beak of an owl shows up, you kind of know what in for. Not anymore. The owlbear in the new version has this new ability to emit a terrifying screech that can cause everyone to become frightened.

We were just able to revisit monsters in a way that allowed us to step back and reevaluate the guidelines and make them more dynamic. One of my favorites is that if you critically hit an earth elemental is that it can immediately crumble, burrow underneath the ground, and then pop up behind you on the next round. There are a lot of cool tricks and tactics that people are going to get to learn and explore. Every time that they encounter something new, it makes perfect sense for what that monster is.

We just had a discussion about how we were changing Vrocks, the vulture-headed demon in the game. I got tired of the fact that the coolest thing about Vrocks is that a group of them together will start dancing. They’re vulture-headed demons that will float up in the sky and do the Dance of Ruin, and you never want them to get that off because it might kill everyone nearby. It’s really cool, but it never happens, because they have to dance for four rounds without anyone hurting them, which never happened. Now, the moment they start dancing, they let off electricity. Every round that you let them dance, it just gets worse. Cool things like that, little touches, I think will make the game more dynamic and make combat more engaging. Monsters are more mobile and have more abilities. There’s just so much more fun to be had. Maybe that’s just me as an evil DM, but I like my monsters to have cool, horrible things they can do to the characters. That’s part of the fun. The story is two-sided. The characters’ stories aren’t heroic if they don’t have heroic deeds and tales about the terrible monsters they defeated. That’s what I’m most excited about: terrifying a new generation of players.

Thanks for checking out this conversation with Jason Bulmahn, director of game design over at Paizo. If you're interested in learning more about Paizo's work, check out my interview with James Sutter on Paizo's Starfinder game, and a later closer look at the final Starfinder release. If you'd prefer to peruse the full backlog of Top of the Table, you can explore all those articles in our dedicated hub. As always, whether you're looking for a recommendation for a great new board game to try, or you're looking for the next tabletop RPG for you and your friends, drop me a line via email or Twitter, and I'll be happy to offer some recommendations customized to your goals.

Get the Game Informer Print Edition!

Explore your favorite games in premium print format, delivered to your door.

- 10 issues per year

- Only $4.80 per issue

- Full digital magazine archive access

- Since 1991