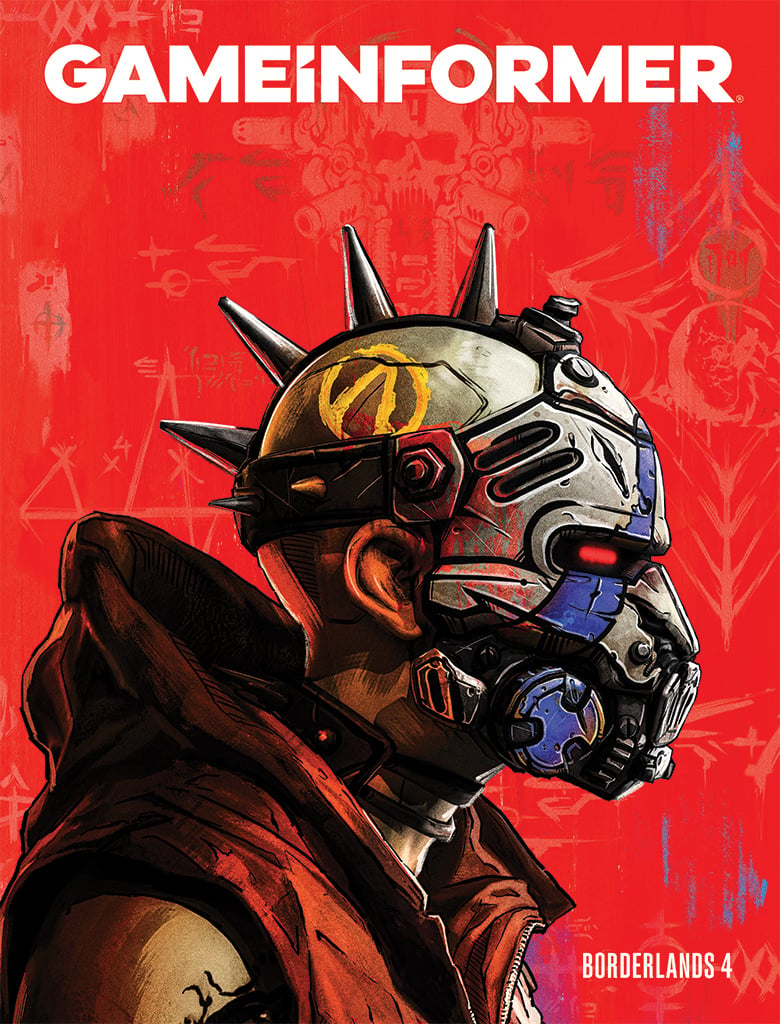

Last chance to get your Borderlands 4 issue when ordered by July 1st. Subscribe Now!

Composer Jim Guthrie Talks Below And More

In the latest issue of Game Informer Magazine (#245) we offer an exclusive look at Capybara Games' Xbox One roguelike Below. Famed composer Jim Guthrie reteams with Capy on this project following work on the much-lauded Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP on iOS, Android, PC, and Mac. We chatted with Guthrie about working with Capy and Superbrothers, and on Indie Game: The Movie, Sound Shapes, and his solo music.

While you're reading this, do yourself a favor and head over to Guthrie's Bandcamp page to play a wide range of music spanning much of his career.

Is Sword & Sworcery your first connection with Capy? How did you meet up?

I met them through Craig Adams [of Superbrothers], who’s the center of all of this. I met Craig around 2004-2005 and he was just a fan of my music. He sent me some mail that had some of his art on it. It was a postcard that had Superbrothers pixel-style art on it. He said he liked my stuff, and he was just sort of saying hello. We kept in touch. I sent him some of my music, some of the unreleased stuff that I had. It just went from there.

Somewhere in between where we met and when the game started, Craig met the guys at Capy and they got talking about making the game, and at some point I was just brought into the fold because Craig liked my music and the guys at Capy knew my stuff] as well as the indie rock stuff I do. One thing led to another, and I was working on my first game with Craig. It was Craig’s first game too. The real vets were all the dudes at Capy, so they were there to steer us all in the right direction and help out. It’s worked out I think.

How did working on your first game compare to your solo stuff and Royal City and what you’d been doing up to that point in your career?

You know, it’s not really that much different. The most challenging aspect of anything when you’re making art or working on anything is just getting inspired. You’ve got to find a way in, and I’ve always made instrumental music, so it wasn’t a huge leap like I was going from writing pop songs to, like, trying to have to think of these ambient soundscapes. I’ve always kind of thought in both worlds.

I was truly inspired by what Craig was doing. I always loved what Craig’s done. I think he’s a genius. The toughest part wasn’t making the music – it was trying to live up to how amazing I thought everything looked and felt and the ideas everybody was coming up with. That’s the hardest part. You don’t want to be the weak link in the chain, so it kicks you in the ass to do your best.

Photo of Jim Guthrie courtesy of Colin Medley

When you first came in were you checking out art or did they have segments of the game up and running to kick start the juices?

I was pretty much there right from day one. Craig liked a lot of the music. I sent him a bunch of instrumental stuff that I had made on a PlayStation, so I had all this weird electronic music. He liked a lot of it and he’d listened to it over the years. When we started the project, he knew maybe two or three of the songs. He had a handful of sounds that we knew we’d maybe start with.

Craig would make these little, crude animations. He’d start with making little videos and little ideas with little characters moving around the screen down a path. The art style was decided on early, but he worked on it over the course of the project, really refined it, and it’s really beautiful. We basically started with that – just videos and taking a song.

We said early on is that we wanted to make an album that you could walk through. We knew the music was going to be pretty important and each song would sort of lend itself to the next scene or the next event in the game. We always knew it was going to be highly emotional on some levels, and that we really wanted to put people in a place and not worry too much. We strayed from the norm in games. I think some people actually found it really boring. For the people who actually got it, it was a really great experience for them and for us. I totally agree that it is a challenging game.

I wasn’t new to gaming, but I was new to making games, so at many times I remember thinking or maybe even saying once or twice, "Hey can we have a couple more explosions or some more fighting or something?" Early on I didn’t get the brilliance of the pace that Craig and Kris [Piotrowski, creative director of Capy] were going for. It was like way more of a meditation. I was like “Why don’t we throw in a chase scene?” or whatever the equivalent of a chase scene would be to pump it up a notch. But it totally messed with the sort of mood they were trying to create. I think I learned pretty fast.

They were the ones who taught me that games can be art. I always knew that games can be art, but when you make a game with the artfulness of it in mind, you understand how games can be art on a whole new level. So that was a good experience for me too. I got really lucky. Not many people get to work on a game that has as much of a vision.

Was your experience on that game how the Indie Game: The Movie people reached out to you?

That’s exactly it. It was the game that made them aware of me. I think they were playing the game or listening to the soundtrack while they were working on the film and they said, “Why don’t we see if we can get Jim Guthrie to do the music because this sounds great?”

I remember from watching it just how it seems like you were able to somehow capture the isolation of working on a game independently and all the stress that they were going through.

Yeah, that’s kind of it. It’s mostly [directors] James [Swirsky] and Lisanne [Pajot]’s vision of how they wanted to portray the life of a game dev. They gave good direction and they really knew what they wanted. It was easy to understand what they wanted based on some early cuts they gave me. Also, I had just done Sword & Sworcery. The game hadn’t been out that long before I started Indie Game, and so I experienced it firsthand. I didn’t go through quite the same sort of stress that those other guys in the film did, but it gets really stressful. Sometimes it gets really existential. It’s easy to get lost when you’re making a game, especially when we weren’t just trying to make an adventure game where you jump around and shoot people and save a princess or whatever.

Our game was a bit more abstract at times and it was hard to even know where it was going. It led to some pretty anxious moments where you sort of question whether or not you’re making something that’s worth anybody’s time. I got to understand how it could be stressful to spend that much time and money on something that nobody will ever give a s--- about maybe. And you might lose all this money. A lot is at stake, so that helped me understand the film a bit better and I could make music a bit better, too.

You created some tracks for Sound Shapes. Did you know Jon Mak before that, or how did that all come together?

I’m really lucky because I live in Toronto and Toronto has a ton of amazing people doing all these great things. I knew Jon through Shaw-Han Liem who’s the other guy on that game. He did a few of the levels – music for the levels – as well. He’s the "I Am Robot and Proud" guy. Do you know that band?

It rings a bell, yeah.

He’s an electronic guy from Toronto and I’ve known Shaw-Han for a long time and he knows Jon Mak just from the game scene. So he and Jon start working on a game and at some point they asked me if I would do a level and asked if Craig would do the art. The whole concept was that – there were a few concepts – but one was that each level would have different art and different music. So they thought “Wouldn’t it be cool to bring Jim and Craig together again on a level?” So Craig did the art and I did the music. We didn’t want to do another Sword & Sworcery thing, but it would be done in Craig’s style. It was through Shaw-Han that I got onto Sound Shapes.

That had to be quite an interesting project simply because all the music is so closely tied into the gameplay and it kind of flows in different ways depending on how the player plays it.

That one was cool because it was a different game mechanic. It’s one of those games, I think, that’s done really well in the sense that it can make you feel like you’re making the music, but the game is going to make the music anyways. You just have to turn it on and off by getting all the little coins or whatever they’re called.

It’s a really brilliant game. Those guys were in the same building as the Capy guys. They opened an office like two floors above Capy. It was pretty awesome, because you just go up and down between the floors, and you get to hang out with a bunch of really amazing people.

It’s kind of hard to explain the process, but I basically just had to come up with a bunch of cool loops that worked as a song when you put them all together. I had to make a song and then deconstruct it, kind of work backwards, and then figure out how they’re going to work as loops. And then make sure that when you reconstruct it, as loops, it still sounds as cool as it did when it was a regular song.

There’s a lot of remixing going on. Have you heard any interesting tracks that players have made?

I was paying more attention early on – I guess it’s maybe been about a year now almost since the game out – but the first six months, I listened to a bunch of stuff. I honestly couldn’t even really hear some of the original loops and sounds, [because] it’s so well done. It’s amazing when you give people a limited toolbox how they can push it out of the box. If you don’t give them a lot of options, then they have to take the limited options they have and really stretch it. I feel like that’s what’s going on in Sound Shapes. What people have done with the levels and the music is, I think, far beyond what anybody thought was possible when they were making game. It’s truly staggering what people come up with.

For Below, it sounds like Nathan [Vella, president of Capy] and Kris reached out to you early on the process?

It was such a great experience working with everybody that yeah, I think they were just like, “We gotta do this again.” That was just too good to not do again, and I was onboard 100 percent. I’ve made music for a long time, but only in the last three or four years I’ve been doing stuff for games. I like it almost more than anything I’ve ever done before in terms of the freedoms I feel like I have. I find it to be extremely challenging, but something that I’m actually really good at. I didn’t really know how well I would be at understanding the medium. But I just feel like I get it in a way that I haven’t really gotten other things.

I would have jumped at the chance to work with those guys again. They got me on pretty early, right from the beginning pretty much. I think they had a bunch of concept art and stuff like that when they first approached me.

Did they give you much direction? Did they give you free reign?

I work pretty closely with Kris. He's amazing in that he’s the perfect example of having a really strong vision and an emotional connection with what it is he’s working on. He really knows what he wants. But he also knows that things are changing and evolving all the time. He’s got a lot of ideas. He basically made me a big .zip [folder] of maybe 100 songs of bands and different tracks and sounds. He’s saying, “Take this and be you. Do what you do, but this is the world that it lives in.” It’s really not that much different than the Sworcery stuff in a lot of ways. It’s going to be a mixture of synthetic and acoustic, and a mixture of dark and really pretty -- sort of a dark sadness. There’s a whole bunch of words like that, I guess: nostalgic, pretty, and lonely. [It’s] just kind of dark and heavy, but really full of light at the same time.

We just talked pretty broadly. The game is still being formed. We’re still working on it, and things are still taking shape. We’re still at a stage where we’re just trying to find where our feet go. And I think we’re almost there, but I think there’s going to be a time when it’s just going to come out really fast. But right now, it’s just trying to figure out what the palette is, what sort of sounds, and what some of the themes are going to be musically. But I do take a lot of direction from Kris. It’s a pretty good conversation. It’s a really good back and forth that we have about it.

Can you talk about making music for the first trailers?

It’s one of those things where you’re working on the game for a long time, and you’ve tried a bunch of stuff, but you still don’t have a lot to show for it in [the form of] a playable game. We had the opportunity to make the trailer to sell the game or to show people the game, so you sort of have to stop making the game and just make a trailer. You’re trying to sell people on something that doesn’t even almost really exist yet in a way. Although, they do have it working as a build. I’m just trying to explain how you have to fast-forward everything and be like, “This is a slice of what it could be if it was fully finished.” And so you refine it all into a trailer. We were just trying to show off the mood and a little bit of the gameplay, and trying to convey that it’s going to be a pretty humbly epic game. It’s not over the top graphics and game mechanics.

That was the first time I was really trying to establish a mood and figure out some of the sounds that I might use for the rest of the game. Because once you can narrow it down, there’re a lot of sounds in the world that you can use in music. If you can just narrow it down to a handful of ideas and sounds, that’s half the battle, and then you can just make the rest of the music based around that small set of rules that you made for yourself. The trailer was the first opportunity I really had to be like, “Okay, this is what I think I really want it to sound like and feel like.”

Going back to what you were talking about earlier, this new niche you’ve been working with. Can you talk about this emerging market for composers such as yourself?

I’ve been making music [for] a long time, but I never would have been able to do what I’m doing now had I not made music for so long before. And also, not only on a skill level, I’m just better at making my own music than I ever have been before. I understand my own process better than I ever have before. Also, there’s this market there, and the Internet is there, and indie games are here. There’s a place to sell them, and there’s a place to buy them, and there are all these game consoles. There are all these machines to play them on. There’s just so much more of everything, and the Internet has made all this possible.

If you would have told me I would be making my living this way, back when I was 15 playing Mario on a Nintendo, if you had told me I’d be making a living doing music for something like that, I wouldn’t have believed you. I wasn’t even ever really sure how I was ever going to make any money making music. It was just one of those things I knew I had to do. I made a decision a long time ago that I was just going to do as much music as I could. I never made any money for years and years and years, but I never saw it like I wasn’t making money. I was just like, “I’m making music,” and I made enough to live. I never saw it as a sacrifice to make $15,000 a year, or whatever I was making a long time ago. It was just what I was doing. So the fact that I can have a few different projects on the go, and know all these really great people, and get my hands on so many cool projects, and be able to work in this field is…I still don’t quite understand it. I’m just kind of a workaholic, so I don’t even look up sometimes. I’m just going nuts and having the time of my life, really.

I imagine you must have a waiting list going.

I do get a lot of offers from people, for films and games. And I have my own solo career that I’m always trying to work on, or nurture, or come up with something new. I managed to put out a lot of records lately in the last five or six years. I do find myself having to say no to a lot of really cool things that I think could be potentially cool. But for me right now, I like it when it’s really close to home. All the guys from Capy live a 10-minute ride on the subway away, and I do lots of work from home. This is a really homegrown thing and that is what I know. I’ve always just worked with people in my community, and in my artistic community. This is all I really know. To make music and art with my friends, I guess, is my strength, or I’m just lucky that it works out that way.

Speaking of solo stuff, what were you able to do with this year’s Takes Time album that allowed you to experiment and not be tied to a specific project.

The most enlightening aspect of being able to put out this record at this point in my career is that I’m so busy, and I’m getting work from all these other places, that I didn’t have to treat this album as something that had to sell in order for me to live. It could just be. I didn’t have to ram it into the ground, and tour it, and try to do press, because that can really kill anything. I think for most people, you’re sick of the album even before you put the album out. You spend all this time writing it, and rehearsing it, and recording it, and mixing it, and mastering it, and by the time you’ve put the record out, you’ve listened to the songs literally 10,000 times each, and you just hate them. And then you have to go out and tour them to death sometimes.

I really like to make music and then never really think about it again. I haven’t toured a lot lately, and it’s because I’ve always struggled with playing live, so it was really nice to know that if I didn’t do a lot of touring, or do a lot of the same channels that one would normally do when they release a record, that I wouldn’t starve. I had all these other cool things to work on. So it was a really freeing record that way, even aside from the artistic things. I just always knew that, no matter what I made, I wasn’t going to go hungry if it didn’t sell anything.

But aside from that, that record sounds a lot more like my older stuff. It’s recorded in a different studio, but, I don’t know if you’ve listened to my older stuff, I think it’s in the same ballpark.

It’s cool to be able to go back to that earlier place and work in a way that fits your preferred lifestyle.

I’m lucky in that I can have a little bit of a solo career, and then have a bit of a career in film and TV doing music for movies, and TV ads, or whatever, and then I have video game stuff that I do. I’ve just been really lucky. I’ve been kind of reinventing myself every year or two doing different things. I’ve been getting work from all over the place. I just feel super lucky to be working, to be honest.

Read more about Below in our September issue (#245) featuring Dragon Age: Inquisition on the cover.