Please support Game Informer. Print magazine subscriptions are less than $2 per issue

Empathy Games: Life, Meet Play

It’s difficult to write about the emerging genre of “empathy games” without dimming their liveliest characteristics. Even their title is nebulous. You might say empathy games attempt to put you into someone else’s shoes, and indeed many do. However, while big-budget titles strap you into iron-clad boots and decorate your torso with rifles and grenades, a game like Cart Life, for example, hands you divorce papers and a small sum of cash and asks you to provide for a daughter.

Empathy games are about lives – even a single life, in some cases. They grab the wide-angle lens that big developers use to tell stories of galactic destruction and they zoom far in on, say, a transgender woman crossing the street. If we’re looking at human life in quantity only, then yes, the stakes are smaller. But through intelligent writing and design choices, these creators have managed to make a rude, overheard comment feel more menacing than a looming Death Star.

Even the “someone else’s shoes” description feels inept, because, like a fairy tale, it implies there’s a universal, moral takeaway. I’ve spoken to several developers for this feature, and not one was concerned with such singular outcomes. Instead, these designers had something to say about their lives, and they decided that expression through video games was the most powerful way for them to tell their stories.

Are empathy games fun? Not necessarily. Frightening, consuming, and alien better describe what I felt, though none were totally devoid of hope. If you turn to video games to escape stress or to feel powerful, you might want nothing to do with the following five games. That’s okay. Their existence doesn’t doom cinematic blockbusters. Make no mistake, though. These designers are chiseling their names into this industry as fervently as others, because it’s their game too.

That Dragon, Cancer

Joel has battled cancer for three years. He’s four years old.

When Joel was first diagnosed with terminal cancer, his parents, Ryan and Amy Green, started a blog to update friends on Joel’s progress. They shared art, poetry, and prayers, and eventually wrote a children’s book. For a creative software architect like Ryan Green, creating That Dragon, Cancer felt like a natural next step.

“We talked about Heaven and we talked about Joel’s sickness like it was a dragon that Joel was fighting,” Green said. “I knew what the title of the game would be before I knew the content. The demo that we have been showing is the recreation of one of my worst nights with Joel in the hospital; one of those moments of desperation and grace.”

Desperation is the perfect word to describe a game that takes place in an intensive-care unit. As Ryan, you pace through a lonely hospital room, pointing and clicking. Sometimes you recite poetry. Sometimes you think about ordering food. Other times, Joel screams in agony, and all you can do is whimper along with him.

“I hate that we’re here,” Ryan’s character cries, though we know he’s not a “character” at all. “I hate that he’s sick.”

Green and his small team hope to release That Dragon, Cancer in 2014 on “as many platforms as possible.”

Cart Life

Cart Life is billed as a “retail simulation,” and while that title is factually accurate, it’s also entirely misleading.

Your default character is Melanie (there are other choices), a poor, recently divorced mother living with her sister, with the immediate goal of setting up a coffee cart downtown. You believe that if you can earn enough money you won’t lose custody of your daughter.

On the first day in the city, you’ll probably get lost. The receptionist at the courthouse is rude to you. You might even forget to pick up your daughter from school. Later, when your sister is about to organize a police search, your ex-husband may show up, daughter in tow. She probably won’t speak to you for a while.

"I want you to start the game expecting Farmville with Coffee, because the characters Melanie, Andrus, and Vinny, themselves, start the week with simple ideas about the path ahead, which quickly become so complex as to be difficult to manage," said creator Richard Hofmeier.

His website sums up the whole of his game with one succinct passage: “Work harder, hard worker.”

Cart Life won the “Excellence in Narrative” award at this year’s Independent Games Festival, as well as the grand prize. You can download it for free here, though deluxe editions are available for purchase.

Up next: Conformity, depression, and gender confusion...

Lim

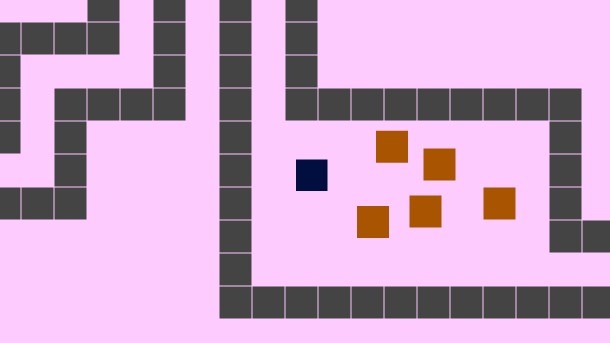

Lim tells its story with squares. Most have one color tone; yours is flashing and brilliant. Though, if you choose, you can bottle up your colors and look like the others.

As you move along, you pass groups of other squares. If you refuse to look like them, they bash you mercilessly. The screen shakes. The collision sounds are harsh. It feels nauseating. There’s no health bar, so you can’t even wait for the quiet of death. If you fit in, you’re rewarded with safe passage, but soon the sounds and the shaking arise again – only this time, the disturbances are internal.

Lim’s designer, Merritt Kopas, said a lot of people believed Lim to carry a powerful anti-bullying message. However, Kopas was influenced to create the game when, during the summer of 2012, she became more aware of how the public perceived her as a trans woman.

“When I made Lim I wasn't thinking of it as an educational game – my goal as an artist and game maker is usually not to educate outsiders about my experience, but to connect with others who share similar experiences,” Kopas said.

You can play Lim for free here.

Mainichi

“Holy s---, YOU’RE A MAN! F---!”

This is a line from the video game Mainichi, which is Japanese for “everyday.” This is also a line that was directly spoken to Mattie Brice, the transgender woman who created the game.

Mainichi is a game about the simple, day-to-day task of getting dressed and meeting a friend at a café. However, as it is autobiographical, players assume the role of Mattie herself. Walking a few blocks seems simple at first, but soon people start talking about your appearance, swearing, and making rude, misinformed comments about your gender.

My second time through the game, I crossed the street to avoid the crowd.

“Many people felt deeply for what it was communicating, either identifying or empathizing with what was going on,” Brice said. “They found it important because it directly communicated an experience – that it was about being a minority was only part of it.”

You can download Mainichi for free here.

Depression Quest

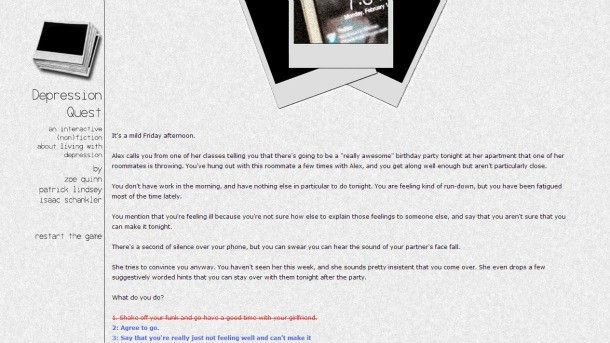

“This game is not meant to be a fun or lighthearted experience. If you are currently suffering from the illness and are easily triggered, please be aware that this game uses stark depictions of people in very dark places.”

This message precedes Depression Quest, a text-based game from designer Zoe Quinn. The game can be absorbing in the cruelest way. You start out level-headed, trying to make the best of bad situations. You intend to open up to your mother. You attempt to make your partner happy by attending parties. Things just have a way of not working out.

By the end, you may be so shaken from your downward spiral that you no longer have the will to make things right.

According to the World Health Organization, depression affects nearly one in 20 people worldwide. As Quinn writes on her game’s site, even if you aren’t suffering from the condition, Depression Quest might “illustrate to people who many not understand the illness the depths of what it can do to people.”

You can play Depression Quest for free here.