Something In The Water: Crystal Dynamics In The '90s

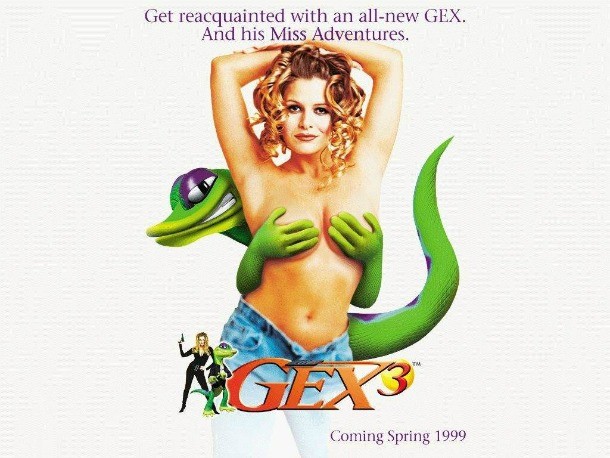

Today, many gamers think of Crystal Dynamics as the studio that pulled Tomb Raider back from the brink of irrelevance. Its upcoming reboot of the series is one of 2013's most anticipated titles. Those with a few more years under their belts recall the company's glory days in the '90s, when it was known for the then-edgy platform star Gex and as the publisher of Silicon Knights' early Legacy of Kain games.

Many people may not know it, but Crystal Dynamics was one of the greatest incubators of talent in the history of video games. Since its inception, several ex-Crystal employees have risen to positions of influence throughout the industry, helping craft multimillion selling and critically acclaimed franchises along the way. Dead Space, Uncharted, World of Warcraft, and Grand Theft Auto all had influential designers and producers on their credits list with Crystal Dynamics backgrounds.

Whether by chance or design, Crystal Dynamics brought together an incredibly talented group of game developers, many of whom formed friendships and working relationships that endure to this day.

A New Breed

"It's bizarre...there was something in the water, I guess," Amy Hennig (pictured above) says while recounting a list of the people she worked with during her stint at Crystal Dynamics. Hennig, now creative director at Naughty Dog, is revered as one of the industry's best writers for her work on the Uncharted series. However, she's worn nearly every hat imaginable in the game industry, including artist, animator, producer, and designer.

Hennig was a relative industry veteran when she arrived at Crystal Dynamics in 1995, already having worked at Electronic Arts on games like Michael Jordan's Chaos in the Windy City as an artist and designer. Positive reports by some ex-workmates eventually lured her to Crystal, which had been founded by Judy Lang, Madaline Canepa, and Dave Morse (who'd previously helped create Amiga).

She wasn't alone. Crystal was quickly developing a reputation as a place where young talent could go to work on new IP - in an environment that was a precursor to the freewheeling culture of the upcoming dot-com boom. Less corporate than more established Bay Area companies like Sega and Electronic Arts, the company provided less-than-seasoned development talent a way in to the industry.

Jeronimo Barrera who has overseen blockbuster games like Grand Theft Auto IV and Red Dead Redemption as Rockstar's VP of product development, was one of the young developers who got a chance to shine at Crystal. "They took a lot of chances on people," Barrera says. "There wasn't necessarily the strongest game development community in those days. Now, there's a whole industry of kids coming out of schools with degrees and things for games. This was a bit more ad-hoc. They took a chance on me and I was in my early 20s. I think my hair was dyed green at the time - it was a real mess. But I was passionate about what I did. I remember before there was a word called 'crunch.' I looked forward to working overnight and being surrounded by these really passionate people. Crystal, as a company, really supported that kind of environment."

Evan Wells (pictured above), now co-president of Naughty Dog, had been introduced to some Crystal employees through a temporary job at ToeJam & Earl developer JVP. He joined the company for a summer job working on the original Gex. "They were trying to ship it in time for me to get to school in September," Wells remembers. "It was supposed to be a summer gig, but summer was ending and the game was not ready and it was going to slip. It did, and they wanted me to stay on because I was working on so many levels. Well, I said, 'I'm a year from graduating; I have to go back to school.' I was also on the gymnastics team at the same time. We had a shot at winning the championship; I couldn't just drop out on them. So I continued to work through my senior year."

Others came from a variety of backgrounds. Glen Schofield, now head of Sledgehammer Games at Activision and the creator of the Dead Space franchise, was more experienced. "I left Capcom because we had spent two years trying to make an engine," he says. "We had all the art built and everyone was learning 3D. I was getting frustrated that we just couldn't build an engine. I was only a senior art director at Capcom and went on to try to be a producer, but I was running into technical difficulties. I go up to Crystal for an interview, and I see the exact opposite. They [had] the art but they couldn't get it together. But I saw this beautiful engine, and I said, 'Damn.' The art and the design, that's my forte, so I was like, 'This is it.'"

Noah Hughes, who still works at Crystal, is a testament to how the company's open structure made it easy for talent to rise through the ranks. Today, Hughes is the creative director overseeing the high-stakes Tomb Raider reboot. In 1993, he was just a kid in the test department.

"It started as a summer job for me," Hughes says. "I started as a film student at San Francisco State. My brother worked at Crystal; he was a programmer. He got me a job. I got in the door as a tester, but I don't think I tested much more than a day or two before I was taking over a lot of the video production, since I had the passion and experience from the film background. So I came in through the classic entry point, but I instantly started weaseling my way into any production role that I could get into."

Crystal quickly became a hotbed of game talent. Other notables include Sledgehammer creative director Bret Robbins, Naughty Dog's The Last of Us lead Bruce Straley, and World of Warcraft's lead content designer Cory Stockton.

Sweet Freedom

Developers found that Crystal allowed for the free exchange of ideas and was structured to encourage collaboration. This started with the building itself.

"It was just a huge, open-plan atrium with open cubicles that were all built in," Hennig says. "It was really neat; it was not the typical type of office. You could stand up and see everybody. There were some offices around the outside, but even those were glass-walled. It was very open and collaborative - everybody could see and hear what everybody else was doing.

Unlike their more established competition, Crystal operated with a relatively blank slate. With few commercially established franchises to lean on, the company (which was operating as both a publisher and developer at the time) had to seek out new IP.

"It felt like a studio that wanted to make really good games but wasn't corporate yet," Schofield says. "There was this free and easy spirit. Any idea could get into the game. If you think about the games we were making, they were all pretty new IPs. Being not corporate, I can remember doing really unorthodox things like, if we needed another level done, asking somebody if they would put in some overtime and saying, 'I'll give you $5,000 extra.' One guy really kicked ass and, at the end of the game, we bought him an electric guitar and lessons. Another woman - she was just this lead engineer on our team who was really fantastic - we got her a trip to Japan."

This approach paid off, as Crystal accrued one of the era's most diverse game catalogs. From the vehicular combat of Off-Road Interceptor to the comedic pop culture-spoofing hijinks of Gex, no genre was off limits at Crystal. It also helped craft externally developed projects from Silicon Knights and Toys for Bob. Amy Hennig, in particular, worked extensively on the Legacy of Kain games.

Not all the partnerships would end well; Silicon Knights eventually sued Crystal Dynamics over the rights to the Legacy of Kain franchise, a legal battle that Crystal won. Jeronimo Barrera recalls a moment that may have foretold things to come: "You know who made a big impression on me at the time? [Silicon Knights founder] Denis Dyack. I remember, one time, something was going on and Denis was unhappy. There was screaming, the cops showed up, and it was all over the place. [Laughs] But, then, I thought, 'That's cool, that's rock 'n' roll, and that's why I'm in this industry.' I never looked at it as unprofessional, I always looked at like, 'Yeah, someone's got some strong opinions about how things should be done and that's that.'"

Within Crystal, teamwork was encouraged with a structure that gave smaller groups of people greater control over their part of a game.

"We started putting levels together by 'pods,'" Schofield says. "We get a group of people that work together - designers, artists, animators - they build the level. They are empowered to make a lot of the level themselves. We still do things in pods [at Sledgehammer] - of course, they are a hell of a lot bigger."

With an open office design and an atmosphere of creativity, the designers would riff with each other, brainstorming ideas that were unique but not necessarily commercial. Evan Wells recalls being impressed by Barrera's (pictured above) outside-the-box ideas, including a never-made valet parking attendant puzzle game. Barrera, for his part, remembers a then-rejected idea that may have been more viable than he thought at the time. "There was an idea we had where you played a cat burglar," he says. "It was a 3D, platforming, run-and-hide game. It didn't go anywhere. It was like, 'Well, who'd want to to play a burglar?' Then Sly Cooper eventually came out and was along those lines."

The other secret to Crystal's success? Lunch. Many former Crystal staffers recall the free, catered lunches the company brought in for its employees, an extravagance that wouldn't be common practice until the tech industry boom later in the decade. The company's approach came at a price, which meant that Crystal Dynamics was frequently strapped for cash. "There were times when they would post how much money we had left on the door, like 'A couple million left!'" Schofield recalls. "But we always managed to get the game out on time."

The Cutting Edge

Free lunches are a nice perk, but developers don't put in 80-hour weeks for months on end for sandwiches. Crystal Dynamics was formed during a period of disruption in the game industry. For the talent that became the backbone of the studio, working at Crystal offered a chance to work on the latest and greatest technology.

"I think an important backdrop to it is the feeling in the industry at the time that frontiers were pretty ripe," Hughes says. "3D gaming as a concept was really just emerging. In that first year, it was about full-motion video. But most of the important technology was just taking games from 2D to 3D. That was an exciting time. You had this nexus of small developer excitement around, 'What can we do with these new frontiers?' I think Crystal Dynamics was one of those focal points."

The company was an early adopter of the 3DO, an expensive system that featured an optical disc drive. Crystal jumped into 3DO development with both feet, creating Gex, The Horde, Total Eclipse, and Off-World Interceptor for the system. However, the 3DO's extravagant $599 price tag (which would be nearly $1,000 today when adjusted for inflation) meant that it quickly sank in the marketplace.

When the 3DO tanked, Crystal became an early Western developer for Sony's PlayStation thanks to Mark Cerny, the most well-known of the early Crystal gang at the time. Cerny, who created the classic arcade game Marble Madness for Atari while still a teen, had strong ties to Japan after moving there to work for Sega on Sonic the Hedgehog 2. Cerny's connections gave Crystal a leg up on its fellow American developers.

"[Mark] got Crystal the very first PlayStation development kit," Wells remembers. "We were able to port Total Eclipse to the PSone. It was the very first approved game that Sony Computer Entertainment America ever gold mastered. It was an honor that Crystal held due to Mark Cerny's relationship with Sony in Japan."

Lasting Lessons

In many ways, Crystal was a product of the times. With a young staff eager to explore new technology and management that allowed them the freedom to do so, it's not surprising that many of the people who cut their teeth at the company have gone on to become some of the most respected and successful creators in the industry. Everyone we interviewed expressed affection for their days at Crystal Dynamics, and in the years since, most have continued to work with alumni.

"Crystal was sort of ahead of their time in a lot of ways - similar to the mentality at Rockstar," says Barrera, who's been a core member of the Rockstar team since its early days. "They were looking at the medium as something serious; something that could compete against television, movies, and books.... It's a lot of the foundations of how I do things today. Even as simple as floor plans, having the open space and having everybody mixed together in little groups. [I learned] the process of really thinking through your ideas and presenting those ideas."

Glen Schofield (pictured above) built his career off the relationships he formed at Crystal Dynamics. Many of the key members of his teams at Visceral Games and Sledgehammer Games are colleagues he met there. When he initially left Crystal, then at a low ebb before it was handed the reins to Tomb Raider by parent company Eidos, he took 20 people with him. Many of them also made the jump to Sledgehammer, including Jason Bell and Bret Robbins.

Amy Hennig stayed on until 2003. Like many alumni, the next chapter in her career was opened up through an old Crystal connection.

"Evan [Wells] called me in 2003," she says. "We'd run into each other at trade shows and stuff like that. He called out of the blue in the spring of 2003 and said, 'Do you want to join us?' I was right in the middle of working on Legacy of Kane: Defiance. I said, 'Well I have a game to finish first, you know, it'd be lousy of me [to leave].' But he just said, 'Well, next time you're in L.A., come see the company and meet the team.' He knew at that point that [Naughty Dog founders] Jason Rubin and Andy Gavin were phasing themselves out and handing the reins over. He was looking for people that he could trust. It was really flattering that he thought of me to come in and be the game director on Jak 3."

For Noah Hughes, Crystal Dynamics is still home. As one of the few employees who has been there for most of the company's history (he left for three years in the late '90s before returning), he has seen the studio's ups and downs. Despite the drastic changes in management, ownership, and technology that occurred through the years, the spirit of those early days remains for Hughes.

"If I look at it from a personal perspective, I loved being here, and I came back after I left," Hughes says. "What it really comes down to is this: I don't make games for a paycheck. I need to get a paycheck while I make games, because I have to pay the bills, but I love making games. It's my life's ambition to create entertainment, and video games are my favorite form of entertainment. For me, to work with enough people that feel that way about it is really the key. You get big enough, diluted enough, jaded enough, and it becomes about other things. What Crystal tends to hold on to is this sense that it's this group of people that need each other to make awesome games and want to do so more than anything else.... Somehow, with Crystal, and it fluctuates - we've gone through tough periods - but it manages to have that feeling for me."

The Crystal Gang

Crystal Dynamics alumni have risen to great heights in video games, and are now responsible for guiding some of the biggest companies and franchises in the industry. This is a partial list of the notable talent that has passed through its doors.

Glen Schofield

GM/CEO of Sledgehammer Games - Produced Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3. Former general manager of Visceral Games and executive producer of Dead Space

Bret Robbins

Creative director, Sledgehammer Games - Worked as creative director on Dead Space at Visceral Games

Chris Stone

Animation director, Sledgehammer Games - Worked at EA as animation lead on Dead Space, The Godfather, and the Lord of the Rings games

Marc David

Currently in tool and programming at Sledgehammer -Programmer on Legacy of Kain: Soul Reaver and many EA titles, like From Russia With Love and Dead Space

Jason Bell

Project lead engineer, Sledgehammer Games - Bell worked on the Soul Reaver and Tomb Raider franchises at Crystal Dynamics

Amy Hennig

Creative director, Naughty Dog - Lead writer for Uncharted series

Bruce Straley

Game director, Naughty Dog - Currently working on The Last of Us

Richard Lemarchand

Former lead designer, Naughty Dog - Recently left the company for a teaching position at USC's prestigious game program

Stephen White

Co-lead tools and engine programmer, Sucker Punch - Former co-president, Naughty Dog

Caroline Esmurdoc

Vice president at online animation school Animation Mentor - Former executive producer, general manager, and COO of Double Fine Productions

Steve Papoutsis

VP/GM and executive producer at Visceral Games and Electronic Arts - working on Dead Space franchise. Former audio/visual lead and producer at Crystal Dynamics

Jeronimo Barrera

Vice president of product development, Rockstar Games - Has played major roles in all of Rockstar's games

Mark Cerny

CEO of Cerny Games - Cerny is one of the most respected consultants in the industry, and has contributed design work to series like Uncharted, Infamous, Resistance, and Ratchet & Clank. Rumored to be assisting Sony with PlayStation 4 development

Lyle Hall

General manger, Heavy Iron Studios

Eric Lindstrom

Longtime creative director at Crystal Dynamics. Now working in the social and mobile space with LudusLabs

Strauss Zelnick

Chairman and CEO, Take Two Interactive - Former president and CEO of Crystal Dynamics

Cory Stockton

Lead content designer for World of Warcraft, Activision Blizzard - Stockton is one of the guiding forces and most public faces of the popular MMO

Sam Player

Executive producer, Electronic Arts - Player works largely in developer relations. Recent credits include Mass Effect 3 and FIFA 12

Steve Groll

Worked in marketing and publicity at Crystal Dynamics, now works in product evaluation and submission at Sony Computer Entertainment

Rob Dyer

Head of partner publishing, Zynga - Dyer was president of Crystal and took over as president of Eidos when it acquired the studio. Dyer has also served as SCEA's senior vice president of publisher relations

John Kavanagh

President, Paramount Digital Entertainment - The former Eidos/Ion Storm vet served as president of Crystal Dynamics

Scott Krotz

A Crystal veteran that's stayed with the company, Krotz is currently the lead programmer on Tomb Raider

Get the Game Informer Print Edition!

Explore your favorite games in premium print format, delivered to your door.

- 10 issues per year

- Only $4.80 per issue

- Full digital magazine archive access

- Since 1991