Our extra-large special edition is here. Subscribe today and receive the 25% longer issue at no extra cost!

Creativity Within The Lines: Immersion In Linear Games

There are dozens of ways to tackle missions in Dishonored. You can forego killing enemies in favor of a stealth-oriented playthrough or you can eliminate anyone standing in your way. Taking cues from games like Deus Ex and Thief, Dishonored encourages experimentation with the ways you approach each situation. However, while there are dozens of methods with which to approach each playthrough, a unified set of missions makes the game a little more linear, creating a tighter experience overall.

As each assassination mission begins, a new area of Dunwall is presented to you where you’re free to explore and interact with NPCs. This freedom allows you to achieve the same objectives in different ways, but in the end you’re doing just that: repeating the same objectives. The story, characters, and missions all remain largely the same between playthroughs. This sense of linearity isn’t a bad thing, though. It helps maintain a strong focus on each objective and provides the backbone for a hybrid game.

Open-world titles provide a thrilling sense of escapism where you’re fully immersed in the world. I’ve spent countless hours exploring the worlds of Skyrim and Fallout 3. The freedom afforded by open worlds encourages imagination and gives me a sense of ownership over how things unfold. As the next console generation approaches, the potential of player freedom is undoubtedly growing and becoming more exciting. However, a game doesn’t have to be completely open to be immersive.

The word “linear” is often mistakenly thought to be synonymous with “boring.” Whereas the lack of an imposed structure in some games is a major draw, the deliberate direction shown in linear games can be perceived as mundane. Being guided from place to place with a select few items or weapons is the polar opposite of an open-ended title.

When a developer can make it fun to be pulled along on a string though, something unique emerges. Take the Portal series, for instance. Each new test chamber presents increasingly complicated puzzles that make you feel like a genius once you’ve solved them. There is only one way to make it from room to room, and you find it every time. Breaking through the walls of the test area to defy the omnipresent GlaDOS creates the illusion of freedom, but this is intentional; players can’t go off the rails without Valve’s say-so. Portal and Portal 2 are linear games, and yet you’re engaged every step of the way.

This generation’s open worlds are impressive, but they can’t mimic the storytelling and level design of linear games. The Uncharted franchise presents stunning set pieces where you’re placed into a carefully designed situation aimed at a specific experience. This authorial intent is what facilitates these moments. For example, the horseback ambush in Uncharted 3 far outshines the miniscule set-piece moments of Skyrim’s optional guild quests. The streamlined presentation of linear games funnels you towards huge moments, while open-world games permit you too much freedom to have the same effect.

It’s understandable that many gamers are burnt out on these moments. Franchises like Call of Duty have made huge impressions with scripted sniper sequences and helicopter crashes, driving you from one mission to the next in search of that next big moment. But when every new sequel attempts to top the one before it with bigger, better set pieces it can become less novel. Linear games need good pacing and conservative use of these major moments to create a lasting impression.

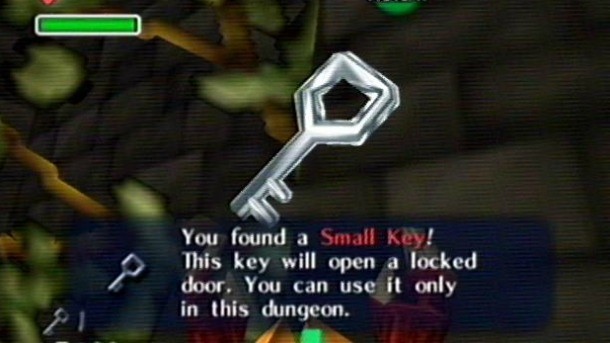

Much like Dishonored, the Zelda games act as hybrids where the linear aspects succeed in balancing the open ended side of things. The in-game world is expansive, but not necessarily open. New areas constantly deny you entry until you have the right tool and some don’t even appear until you complete specific dungeons. While Hyrule is fun to explore, the linear puzzles in the form of dungeons are the main draw of the games. Only one key opens the door blocking your way, and there is only one way to get it. Although the thrill of killing enemies several different ways in Skyrim excites me, figuring out the one method to kill a Zelda boss at the end of a dungeon is a much more rewarding experience.

Open world games have always had to create large, believable worlds in order to absorb you. The Grand Theft Auto franchise lures you in with its vibrant cities and colorful inhabitants. Should you choose to tackle a scripted mission, they usually feel right at home in the context of the environment you inhabit. When the occasional firefights erupt, however, it’s apparent that less time went into these sections than they did in a more focused game like Halo: Combat Evolved. The shootouts in Halo are infinitely more engaging, showcasing an attention to minutiae rather than the whole world itself. Each minor encounter with the enemy grabs you and reels you in, leaving your heart rate high until the last alien is dispatched. As opposed to GTA, the levels are linear and you’re seldom given the chance to roam, but it isn’t any less successful at investing you in the experience.

There isn’t just one way to create an immersive video game. Some titles drop you in a massive world ready to be explored, while others guide you along with good writing and sound level design. I love believable worlds that encourage me to explore every nook and cranny. Often though, a linear game can elicit the same amount of commitment. My favorite games are ones I can get lost in, but that doesn’t mean I need complete freedom to do so.

Get the Game Informer Print Edition!

Explore your favorite games in premium print format, delivered to your door.

- 10 issues per year

- Only $4.80 per issue

- Full digital magazine archive access

- Since 1991