Please support Game Informer. Print magazine subscriptions are less than $2 per issue

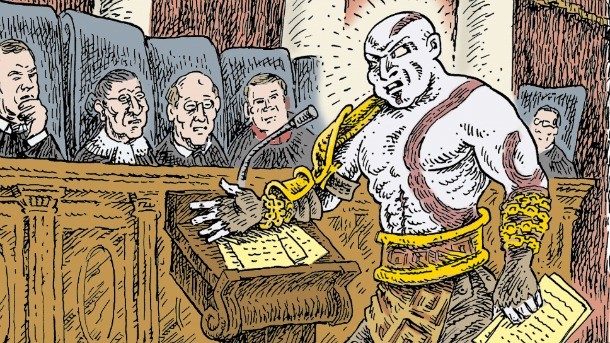

Enemy Of The State

This fall is an important season for the video game industry. Blockbuster titles like Halo: Reach, Call of Duty: Black Ops, and Assassin’s Creed: Brotherhood will arrive. Sony and Microsoft will introduce new motion-controlled peripherals. But another major event is also on the docket: the industry’s day at the biggest court in the land. For the first time, video game legislation restricting the sale of video games to minors is going before the U.S. Supreme Court. The Entertainment Software Association has successfully contested the California law as unconstitutional on first amendment free speech grounds twice already. We’ve seen these types of laws proposed and defeated for years, so why is this one any different? We went to both sides of the argument to find the answer.

What’s the law say?

The California bill demands that violent video games be marked with a two-inch square label on the front of the box. Retailers that sell those games to minors would be liable for up to $1,000 per violation. Take a big game on its release date and a bad sales clerk, and that could add up to a hefty chunk of change.

The law eschews the ESRB rating system, and demands a separate set of descriptors be applied. It describes a violent game as one in which "the range of options available to a player includes killing, maiming, dismembering, or sexually assaulting an image of a human being." The bill also details what it means by each of those words and extends its description to include characters with "substantially human characteristics."

According to the bill, a game falls under the law if "a reasonable person, considering the game as a whole, would find it appeals to a deviant or morbid interest of minors...it is patently offensive to prevailing standards in the community as to what is suitable for minors...or it causes the game, as a whole, to lack serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value for minors."

If some red flags are popping up as you read those descriptions, you’re not the only one. The ESA has some problems as well.

What’s at stake?

Game Informer asked ESA spokesman Rich Taylor about the challenges the bill presents to the gaming industry. "Do you want the government even beginning to get into the area of deciding what can and can’t be sold and marketed, and ultimately, what can and can’t be created?" Taylor asked. "As someone who enjoys video games, do you believe that form of creative entertainment deserves the same constitutional protections afforded to books, films, and music, and other forms of popular entertainment? Why should this incredibly dynamic industry be treated differently?"

To many gamers, the law sounds redundant. After all, the ESRB already labels M-rated games, and retailers regularly enforce them. This law would complicate the relationship between publishers, retailers, and gamers. "If you’re a retailer, you want to be able to sell the products that come to your store without fear of potentially being on the wrong side of the law," Taylor surmises. "The easier course might be to not carry that game at all. And when retailers make that decision, it means there are fewer places to sell that game for those that create them." Connecting the dots gets easy from there on out. Game publishers and developers need to make money to produce new games and turn a profit. If retailers won’t sell a game for fear of legal penalties, the likelihood of those games being made decreases.

Moreover, the ESA has concerns about the precedent set by the law, both in terms of future video game legislation, as well as limitations set on other forms of media. "It’s a law that would treat creative works in a way that’s inhospitable to the first amendment," Taylor continues. "That’s a very dangerous place for our country to be considering heading."

Do the undead creatures of Left 4 Dead 2 have "substantially human characteristics"? If so, do players inflict injury on them in a way that is "cruel" or "depraved"?

The Other Side

But are all those arguments legitimate? The California law isn’t concerned with other mediums – only video games. And from the perspective of the state, if the retailers can’t successfully enforce their own sales limitations, how will it ever learn without a penalty? That’s the point of view espoused by the office of California State Senator Leland Yee, the bill’s original author. We spoke with Yee’s chief of staff, Adam Keigwin, for some clarification. "What’s at stake is whether states have the right to pass laws that may restrict what is harmful to kids," Keigwin says. "In the past, the courts have ruled in favor of protecting children on so many issues. There’s certainly a heck of a lot less evidence that pornography has any harm to kids, and yet they have ruled that we can limit their access to pornography. They’ve ruled time and again that we can limit children’s access to several things: driver’s licenses, firearms, the death penalty, life without parole sentences in certain cases, tobacco, alcohol." Citing studies that draw connections between real life violence and the playing of violent video games, California hopes the Supreme Court will lean on the side of child protection.

But why is a law necessary? The ESA claims to have one of the strongest entertainment ratings organizations in any medium. "We take great pride in the Entertainment Software Ratings Board," Taylor says. "The Federal Trade Commission looks at movie ratings, music labeling, and video game ratings every two years or so. Consistently, and increasingly so, it says that the ones that are doing the best job in educating and being clear at the retail level is the video game industry."

Citing the same organization, Keigwin highlights some very different findings. "At the time that they passed this law, a federal trade commission study showed that well over half the kids 14-16 years old were able to purchase ultra-violent video games," he claims. "That number has improved, and I’ll give the industry credit for that. With that said, it’s still nearly 30 percent of young kids that are able to purchase ultra-violent video games."

Keigwin also isn’t satisfied with the way games are classified in the first place. "The ratings system itself is flawed. They have an AO rating – they don’t use it even though the AO description says that it’s for extreme violence. They’ve never rated a game AO based upon violence. So why have it? It sends the wrong message to parents who look at an M game and say: ‘Oh, well if it was so bad it would have gotten an AO rating.’ A parent doesn’t know that a game has never been rated AO. That’s the problem. ‘Mature’ is a very ambiguous term."

The ESA takes issue with this line of reasoning, citing the detailed descriptions that accompany each rating, and proposes another solution that avoids treading into legislation. "We think government efforts should be focused on joining with us to ensure greater understanding and use of our system, because it’s the parents – not the government, and not the gaming industry – that should make decisions about what games are suitable for their children," Taylor declares.

Next up: The big unresolved questions, and what you can do to get involved.

(This feature originally appeared in Game Informer magazine issue number 210.)

Games like Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 seem to still be getting purchased by minors. Laws like the one in California aim to abolish the practice

Unanswered Questions

Regardless of how the Court rules, a plethora of unresolved issues remain cloudy. Specifically, how will California enforce this new law?

"The law itself presents many unanswered questions and many dangerous precedents in its construction," Taylor tells us. "I think that’s the reason that the courts that have looked at it until now have said with no equivocation that this is an unconstitutional law. I would say to direct that back to Mr. Yee and those in support of the law, including the governor of California, who appealed this up to the court."

We took his advice, and Yee’s chief of staff offered a simple answer. "If they rule in our favor, the law just gets to go into effect," Keigland says. "I don’t see the video game industry struggling over this, although you would think they may, because they are fighting this so hard. So you think they must be making a lot of money off of sales to kids."

The seemingly straightforward implementation of the law is where things get dicey. California is fundamentally opposed to the ESRB’s approach, so that system won’t be used to determine which games are deemed violent or not. Instead, each individual publisher would need to make those decisions based on the wording of the law and hope that they’re not in violation. Would a T-rated military shooter be considered inappropriate because it includes depictions of killing another human? How about the killing of aliens – are the Covenant sufficiently humanlike to be protected under the law? Does killing zombies count considering they’re already dead? It’s tempting to be flippant, but that’s exactly the point. These off-hand examples illustrate the dilemma that would face game makers if the law were upheld.

There’s also the issue of downloadable gaming. California’s law specifically addresses retail releases. However, services like Xbox Live allow purchasers to buy M-rated games, leaving it up to parents to set parental controls if they want to limit the games their children can purchase. Is it fair to hold downloadable games to a different standard, when sometimes the games available online are identical to those sold in stores?

Then there’s the potential avalanche of similar laws in other states and the undue stress that would place on game creators. Eleven states formally support California’s case – Connecticut, Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Texas, and Virginia. If the law passes, other similar laws could be passed in those and other states. Would each state have its own definition of game violence? Would each require a different sticker on the box? Would publishers be responsible for keeping track of each set of statutes in order to legally sell their games?

Regardless of the court’s ruling, one overriding question behind the disagreement remains – are violent video games a negative influence on children? California has numerous studies they’ve submitted that claim they do, and the game industry has evidence to the contrary. "The violent crime rate among youth has descended almost as fast as our industry has grown," Taylor says. "New media is often greeted skeptically and hostilely by some, and we’re no different."

Make Your Voice Heard

No matter how you feel about the law in question, gamers owe it to themselves to get involved. If the presence of this law before the Supreme Court isn’t a wake-up call, it’s hard to know what will be.

If you’re displeased with the way the ESRB rates and retailers sell video games, contact the organizations and let them know how they should improve. Alternately, if you sympathize with the ESA and believe video games deserve to be protected speech like any other form of art or entertainment, then you may want to look into the video game voters network. You'll be able to easily sign up to join the organization, and read the network's take on video games and first amendment issues.

"There are over 200,000 registered voters who are game enthusiasts, who are keeping track of policy as it relates to computer and video games," Taylor says. "If someone comes up with a misguided, unconstitutional, hostile proposal, the network contacts them. That speaks louder to a policy maker or a politician: to hear from constituents that say ‘I disagree on your stance on that.’ If that 200,000 number were to become a million or more, it would be the kind of number and voice that would make clear to legislators at the local, state, and federal level that gamers are engaged. Gamers are paying attention, and they’re going to register their satisfaction or dissatisfaction at the ballot box."

One million gamers is about one quarter of the people who read this magazine every month. It’s about an eighth of the players who bought the last Call of Duty game in the first week of its release. It’s less than a tenth of people who currently hold World of Warcraft accounts. It’s not an unattainable number, so if gamers want to prove they’re more than disconnected stereotypes that never come out of their mothers’ basements, then it’s time to step up and be counted.

(This feature originally appeared in Game Informer magazine issue number 210.)

Art by Ken Avidor